DEATH ON DEMAND

The case against euthanasia

{The picture is of an assisted suicide pod}

‘If death were to become not just an option but something close to an entitlement through the bureaucratic processes that an act of parliament’s provisions impose, we would, in my view, be altering fundamentally the way we think about mortality.’ (Gordon Brown.)

INTRODUCTION

I've ummed and arred about whether to write a piece about assisted dying or not because I've blogged on this subject already once before and also because there has already been a deluge of articles on the subject more recently, many of which have been written by people with far more expertise and knowledge of the various inter-related subject matters which pertain to the topic than I have.

However, my previous blog on the subject was as much an Alisdair MacIntyre/Patrick Deneen-style critique of liberalism in general as it was of assisted dying in particular, and whilst there have been many well-written articles published about assisted dying recently from a variety of different perspectives, I have my own perspective on this issue informed by my own experiences, both as a son, who at the age of 22 watched his mother dying from cancer in a hospice, and also as a psychiatric nurse of the last twenty years (counting my student nurse years) who has concerns about how assisted dying will play out in the real world with respect to people who suffer from various mental disorders.

So for these reasons I wish to add my own thoughts on the issue to the pile, with particular emphasis upon my two main concerns about ‘assisted dying.’ Namely, that I fear that it will ultimately be used to legitimise austerity and also because I suspect that its scope will inexorably be expanded to encompass people with mental disorders and undermine suicide prevention in this country. Put simply, my worry is that ‘assisted dying’ is a slippery slope towards a death-on-demand service in which suicide becomes normative and soft-eugenicist attitudes towards the elderly, infirm, disabled and the mentally ill crawl out from the darkness and towards the light of the public mainstream

THE RISKS TO PALLIATIVE CARE AND PUBLIC SERVICES USED BY THE VULNERABLE MORE GENERALLY

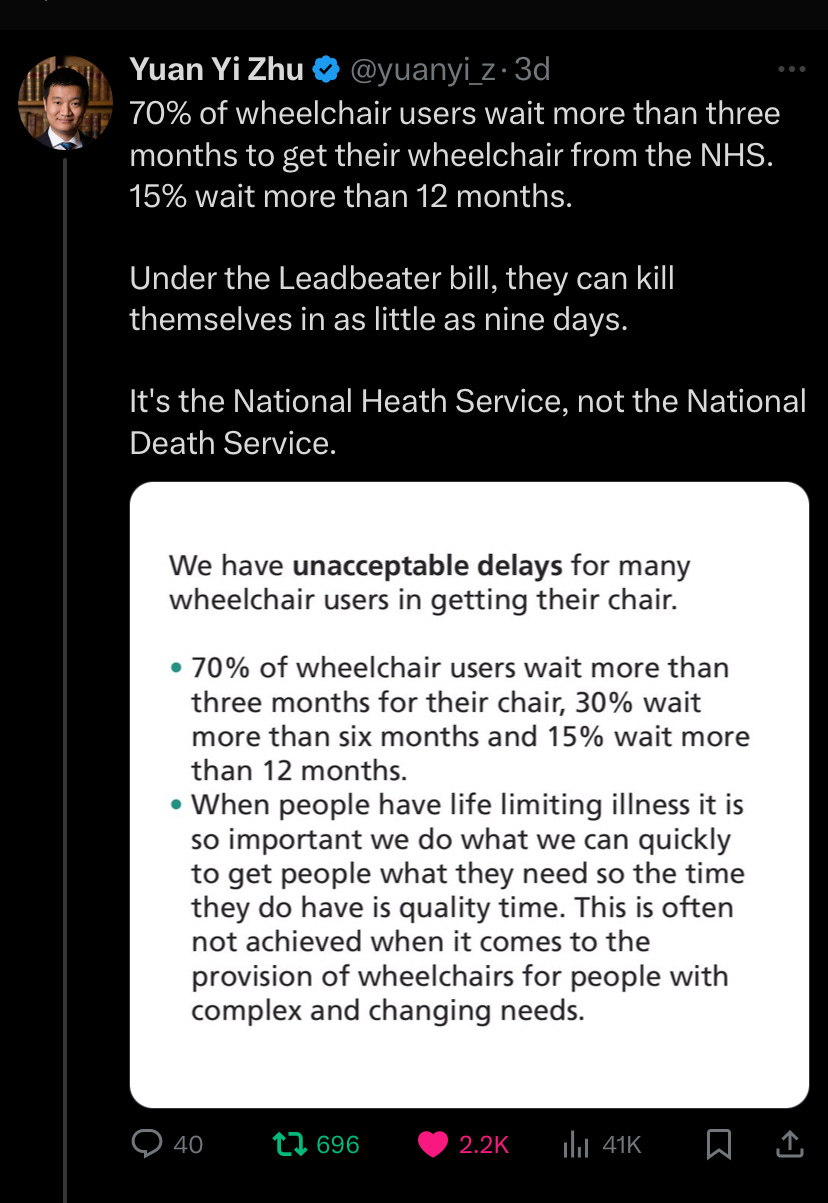

On Friday, the 29th November, 2024, parliamentarians will vote on Kim Leadbetter’s private members bill and decide whether or not to legalise euthanasia in England and Wales. If adopted, the bill in question would make it legal for over-18s in England and Wales who have mental capacity and are expected to die within six months to be assisted to end their life. They would have to be assessed by two independent doctors and have the decision signed off by a high court judge.

As Gordon Brown has written; ‘both sides in the assisted dying debate share a common concern: the genuine compassion felt for all those suffering painful deaths. Making possible a good death for all is one of the last great, yet unattained causes.’

Gordon Brown is surely correct that public support for euthanasia is motivated by a strong sense that people should not suffer unnecessarily. We all share that concern, but we differ in regards to how best to achieve this. In my opinion, the best way to achieve that aim is via proper investment in palliative/end of life care.

My own mother experienced that care in 2002 after her bowel cancer metastasised to the rest of her body. However, the Palliative/end of life care-sector in this country is currently in a parlous state.

It was recently reported that many of the UK's 200 hospices, which together support about 300,000 people annually, face cuts and redundancies and that the hospice sector’s finances are apparently the worst they’ve been in 20 years with Hospice UK revealing that the hospice sector gets more money from its charity shops than from the government. Adult hospices have to raise around two-thirds of their income through charity fundraising, while for children’s hospices the figure rises to around 80%.

There are three child hospices in the country and one of them has only remained open thanks to a flurry of charitable donations from the likes of Home Bargains after a publicity campaign.

The adult hospice in which my own mother received care faces a one million pound deficit and also faces an uncertain future. Whilst up to 90% of people are estimated to have palliative needs at the end of their life, less than 50% of people dying in the UK currently receive it.

My concern is that legalised euthanasia will make this situation even worse by reducing incentives to invest in the sector. It was only two years ago that NHS provision for palliative/end of life care was even made a statutory requirement to ensure that NHS commissioners were mandated to provided access to such services but yet it is still the case that only 11% of hospital trusts offer face-to-face access to specialist palliative care 24/7. This problem is compounded by the fact that over the next ten years 33% of palliative care consultants are set to retire.

Additionally, as previously discussed, hospice care is still largely funded by charitable donations. Two years ago ‘The Guardian’ published an article entitled ‘Hospice Care is a right not a luxury’ in which the author stated: ‘the state contributes under 30% of the £1.6bn hospices spend, there is no formula for how much each hospice gets (they negotiate individually), and the rest is charitable. Provision is thus patchy: wealthy areas are better served than poor, and some places have no specialist service.’

The sad reality is that not much has changed since that article was written and the introduction of euthanasia risks making things even worse. At a time when less than 50% of the people who actually need palliative care actually do receive it, when as much as two-thirds of the funding for such care is reliant upon charity, and when NHS funding for palliative care is rationed, even though there is an actual legal duty to provide it, then the potential for euthanasia to reduce incentives to fund palliative care properly are obvious. We only have to look at the other countries and jurisdictions that have legalised euthanasia to see this.

{Source}

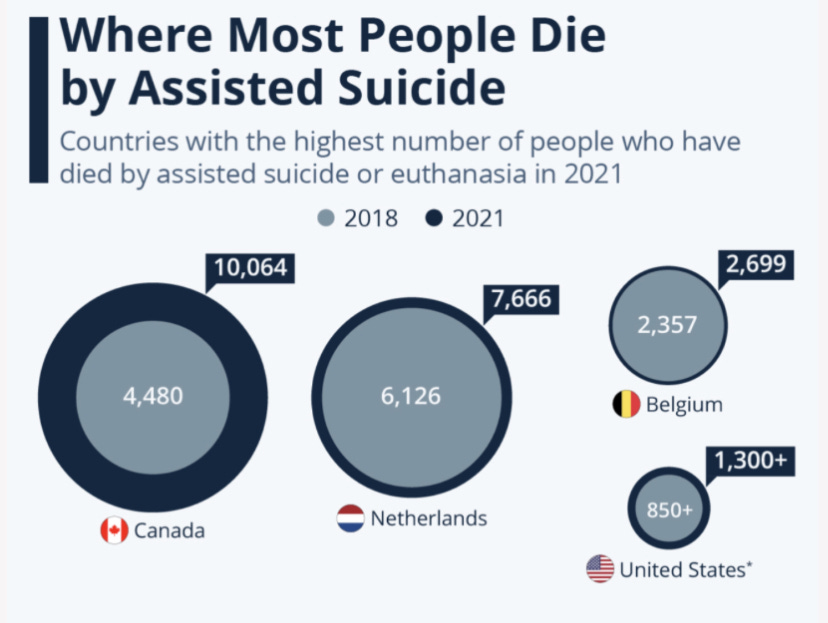

In Australia, New South Wales cut palliative care spending by 30% upon legalisation of euthanasia. In Canada only 15% of patients have access to quality palliative care, it also has some of the lowest social care spending of any industrialised country in the world and fewer than a third of adults receive the type of mental health care that they require. In British Columbia, a private hospice was shut after it refused to offer euthanasia.

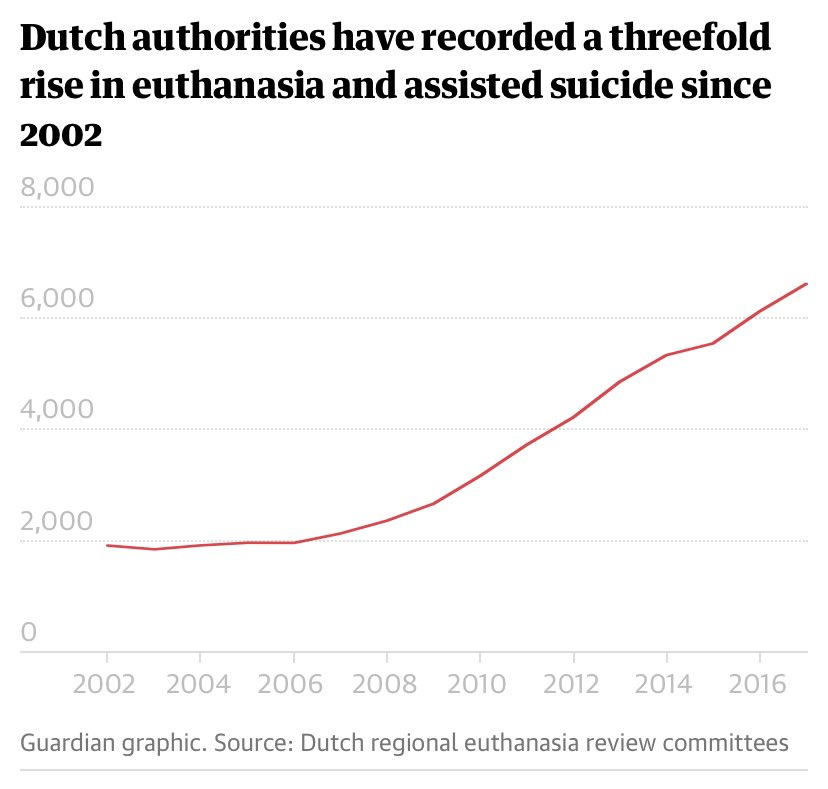

In the Netherlands, euthanasia was originally meant to be a last-resort option in the absence of other treatment options but palliative care consultations have never been a mandatory part of the process.

In Belgium, requests by the Belgian palliative care sector to include an obligatory palliative care consultation were denied. In Switzerland, in 2006, the university hospital in Geneva reduced its already limited palliative care staff after a hospital decision to allow assisted suicide.

As J.Pereira has written, ‘There is evidence that attracting doctors to train in and provide palliative care was made more difficult because of access to euthanasia and physician assisted suicide, perceived by some to present easier solutions, because providing palliative care requires competencies and emotional and time commitments on the part of the clinician. At the United Kingdom's parliamentary hearings on euthanasia a few years ago, one Dutch physician asserted that "We don't need palliative medicine, we practice euthanasia".’

When polled only 5% of palliative medical specialists expressed support for euthanasia, which should tell us something.

{source}

THE ELEPHANT IN THE ROOM

The elephant in the room in the euthanasia debate is the ageing of our society and its fiscal implications.

By the end of 2026, it is estimated that the UK will have more people aged 65+ than under 18 for the first time ever. Since the 1990s the number of people living beyond the age of 90 has tripled and the number living beyond the age of 100 has also tripled in just a decade. When the NHS was initially established, there were only around a quarter of a million people in Britain in their late 80s or older, a cohort requiring six to seven times as much health spending; whereas there are now more than one and a half million people in that age group.

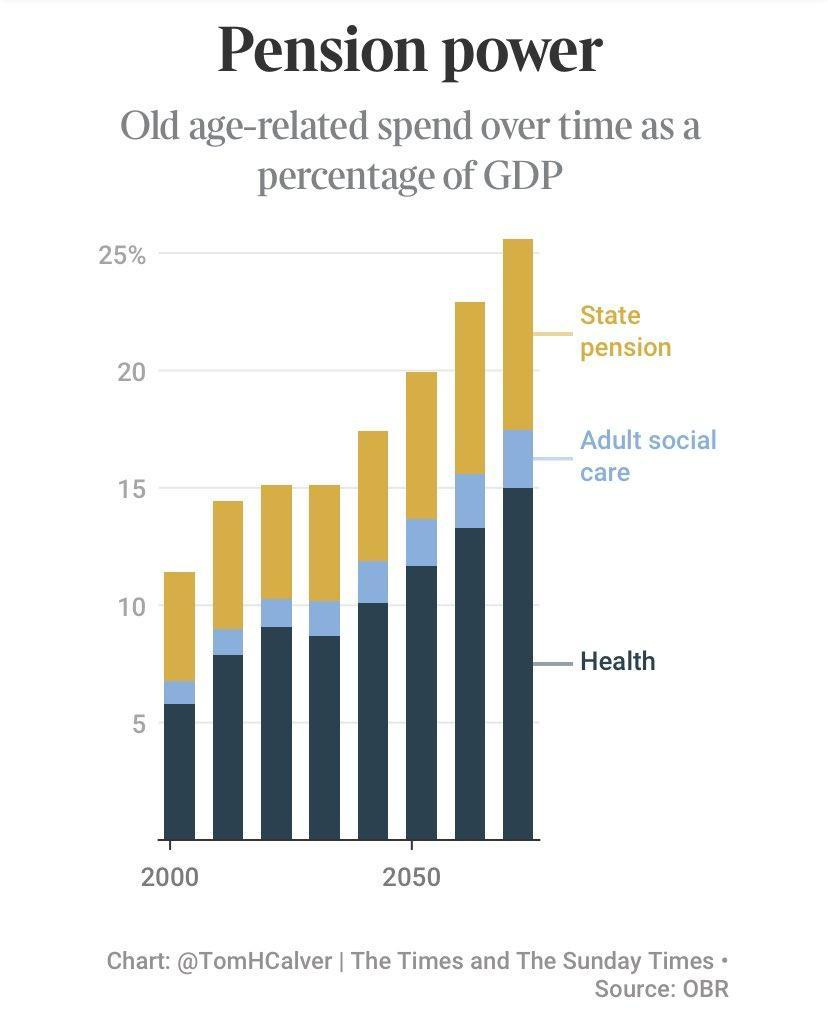

To state the obvious, this has huge implications for the public purse. We are living longer and having fewer children, which means that, over time, we are going to end up with more pensioners and fewer working-age people. In monetary terms, this is not sustainable in the long-term. The Office for Budget Responsibility has stated that age-related spending will have to rise from 15% of GDP to about 26% by 2070 due to the fact that there will be more pensioners but fewer working people, according to current demographic trends, and it is also estimated that spending on the state pension will also double over the same time period.

The danger of introducing ‘assisted dying’ into the economic context in which we find ourselves in, with a ballooning care bill which is literally bankrupting local councils up and down this country— one in seven adults aged 65 face lifetime care costs of more than £100,000, out of every £10 spent by local government, more than £6 is now spent on social care, and spending on social care has increased from 53% of expenditure in 2009-10 to 66% in 2022-23,—should be obvious to everyone.

The risk is that ‘assisted dying’ becomes the less costlier method by which the state manages the ballooning care costs of an ageing society, rather than having to invest in the care and support of an increasing number of people with complex and long-term health and social care needs.

It isn't just the palliative care sector which is potentially at risk if euthanasia is legalised either but also a whole range of services upon which the vulnerable rely. The risk is that expanding the remit of ‘assisted dying’ programmes inevitably becomes the inexorable response of the state to the ballooning costs of an increasingly ageing society, rather than expanding the state’s capacity to care.

Why reform social care or healthcare, or put more money into the care of the elderly in general, or of the disabled, or the mentally ill, when you could simply just expand the remit of ‘assisted dying’ programmes instead? That will be the temptation. The economic logic is obvious. You would have to be very naive to imagine that this could never happen.

{source}

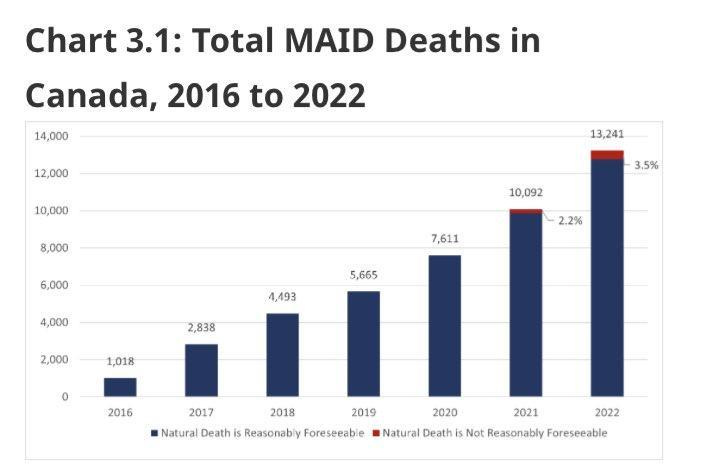

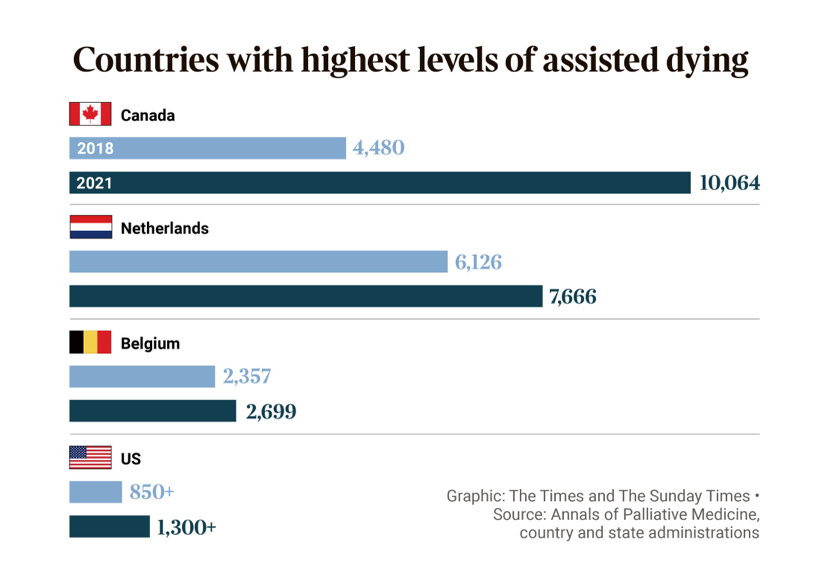

In fact, we do not need to imagine. As Wesley Smith has noted, whilst healthcare in Oregon is rationed, ‘assisted dying’ never is. Meanwhile, seems determined to fast-track itself towards a real-life equivalent of Logan’s Run at break-neck speed. Euthanasia was only legalised in Canada in 2016 but already accounted for 4.1% of deaths in the country by 2022, an increase of 31.2% from the previous year. In the Canadian province of Quebec, the euthanasia death rate is even higher, at 7.3%.

There is every sign that the Canadian euthanasia death rate will increase yet further over time too. Indeed, over a quarter of Canadians believe that people should have access to euthanasia just because of poverty alone. Thanks in part to its assisted dying policies, Canada now has the dubious distinction of being a global epicentre for organ harvesting.

{source}

As noted previously, Canada combines the most permissive euthanasia regime in the world with restricted access to palliative care, social care and mental health care. Which is perhaps not a coincidence. More than one in five Canadians — an estimated 6.5 million people — do not even have a family physician or nurse practitioner they see regularly. A situation which has worsened since ‘medical assistance in dying’ was introduced.

{source}

As disability rights campaigner Liz Carr has noted; ‘Euthanasia in Canada is becoming a solution to the problems of a failed social care and medical care system.’

This observation is borne out by the statistics. A recent report on assisted dying in Ontario noted; ‘a disproportionate number of people who died by assisted dying when they were not terminally ill (29%) came from Ontario’s poorest areas. This is compared to 20% of the province’s general population living in the most deprived communities.’ The report noted that; ’In Ontario, more than three quarters of people euthanised when their death wasn't imminent required disability support before their death…. The figures suggest poverty may be a factor in Canada’s nonterminal euthanasia cases.’

An assessment of assisted suicide by the Canadian government, even noted that legalisation could reduce annual health care spending across Canada by between $34.7 million and $138.8 million. The risk that ‘assisted dying’ injects perverse incentives into our health and social care systems, resulting in reduced access to care and support for people with the most complex and long-term health and social care needs, whilst, at the same time, increasing access to ‘assisted dying’ procedures for the same group of people who have been deprived of the care and support that they require, simply because this is more economical for the state, is a very real possibility.

Which brings me to my second main concern regarding euthanasia. Over and over again, the public figures who have come out in favour of euthanasia have emphasised that their reasons for supporting it rest upon the liberal principles of individual choice and autonomy. The problem with legalising euthanasia on this basis is; why should that principle only be extended simply to people diagnosed with a terminal condition who have six months to live? If ‘patient choice/individual autonomy’ is the all-important value then surely everyone should have that choice, right? Or else {working within the grain of this ethical perspective,} we are operating in such a way as to restrict individual autonomy, and that simply won't do.

As Trevor Stammers correctly puts it: ‘Once the principle of individual autonomy taking precedence over the protection of the vulnerable has been conceded, as it has by this recent vote, its extension to other groups is inevitable.’

If this is the basis upon which euthanasia is established then it will inevitably be prone to expansion and that means, as in other countries, people with non-terminal conditions such as mental disorders will end up being euthanised too. Ergo, the much vaunted ‘safeguards’ contained in Kim Leadbetter’s private members bill, and upon which public support for ‘assisted dying’ rests, are revealed to be little more than window dressing for a law which will inevitable mutate over time into a national suicide service, a form of death on demand.

To quote Henry George; ‘As Ilora Finlay and Robert Preston demonstrate in Death by Appointment, in country after country, what started as a measure intended only for extreme pain in old age or the terminally ill expanded to non-fatal but painful conditions; then to non-fatal, non-painful ailments; then to those in psychological distress. In doing so it moved down the age-range to younger and younger cohorts, eventually to adolescents and even children. All despite incessant reassurances of guardrails and safeguarding. The slippery slope is not a fallacy. It is simply a fact.’

As Amanda Achtman has written; ‘If assisted dying is a compassionate response to people who are suffering, as those who are now arguing for a change in the law in the UK argue, then there is no reason why it should be limited to those who are terminally ill. Many people suffer – not only physically but also psychologically – throughout life. If euthanasia is an expression of dignity and autonomy, then why limit it to select demographics.’ As Sonia Sodha puts it; ‘There is no fixed definition of what constitutes a “terminal” illness and medical experts say it is impossible to accurately predict life expectancy beyond a few days; so legislation could end up covering people living with a wide range of conditions with huge latitude for doctors on what they sign off.’

Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands quickly extended access to assisted dying to people with non-terminal Psychiatric conditions after legalisation, even though there is evidence to suggest the wish for a hastened death is reduced when mental health problems are treated effectively. In Oregon, access to assisted dying has been extended to people with eating disorders. Indeed, the BMJ recently reported that ‘at least 60 individuals with eating disorders have died through physician-assisted death, including in jurisdictions limiting the practice to terminal conditions. Of these, one-third involved women under 30.’ In the Netherlands and in Belgium, access to euthanasia has been extended to people with personality disorders (as well as people with learning disabilities and autism and dementia and depression and even prolonged grief.) Incidentally, 69-77% of people who die by psychiatric euthanasia are women.

This is worrying, because research has demonstrated that the failure of society to provide adequate care and support to those with long term mental health conditions is, in large part, what motivates people in those groups to seek assisted dying. If an assisted death becomes a more accessible option than meaningful care and support for people with long term conditions (such as serious and enduring mental disorders,) then we risk opening the floodgates to the normalisation of suicide more generally.

Research has found that that ’assisted suicide laws lead to a substantial increase in total suicide rates and, if anything, are associated with an increase even in unassisted suicides. This effect is most pronounced amongst women.’ This research estimates that assisted suicide laws increase total suicide rates by about 18% overall, and for women, the estimated increase is 40%. In Oregon, which legalised assisted suicide in 1997, suicide rates are more than 40% higher than the national average. Availability and access to palliative care, on the other hand, is associated with reduced suicide risks.

You don’t need to be a suicidologist to see how ‘assisted dying’ policies can undermine suicide prevention efforts. If you present death in positive terms as a solution to the existential problems of living then that risks nudging more people into contemplating a final solution, as it were.

Research demonstrates that the biggest reason people seek euthanasia is because they don't want to be a burden on their loved ones. If we make it easier for the most vulnerable people in our society to access death than to access the support that they need to live then inevitably that sense of burden will be felt more keenly. What starts as an option to die risks transmogrifying into a a feeling that it is one’s duty to die if you happen to be disabled, old, sick, mentally ill, or just vulnerable in a non-specific sense. Euthanasia laws therefore risk creating an environment in which more people feel an obligation to die and, in turn, a changing dynamic in which ‘assisted dying’ starts off the exception but ends up as the norm.

What then is the substantive difference between such a policy and a form of soft-eugenics? An ageing population is going to be the biggest demographic challenge we face this century and health/social care costs will spiral accordingly. The temptation for governments to expand ‘assisted dying’ to more people, rather than invest in palliative care or social care or mental health care, will inevitably follow.

If ‘assisted dying’ is enshrined in law, why would any government invest in services to help people manage their long-term and complex conditions when they could just cut costs by expanding ‘assisted dying’ to ever more people instead? Ultimately, the problems to be found in ‘assisted dying’ systems such as the Canadian MAiD system are not bugs but features, which means that it can happen here too, if we are foolish enough to follow down the same path.

Ultimately, this is not a left-wing v right-wing issue. If you’re left-wing then you should be opposed to ‘assisted dying’ because it will be used to legitimise austerity (as we have already seen in Canada.) The likelihood is that euthanasia will never be rationed but access to care and support always will be. If you’re right-wing then you should be opposed because you are giving the state, in the form of the NHS, the ultimate power over life and death. Can we fully trust any state with that level of power? This is the question that we all must ponder.

I was originally in favor of a very liberal assisted suicide program, even writing on it. Seeing its actual impact here in Canada and the way it has been used has changed my mind. In theory a very conservative program with many guardrails would be good, but the logic of the state and the toxic empathy of the assisted dying community/practitioners makes this hard to achieve in practice.

Closer to home the Netherlands has assisted the suicide of people with autism and personality disorders.

Assisted dying laws multiple countries have led to the deaths of at least 60 people with eating disorders, including where assisted suicide is limited to terminal conditions only. Of these a third included young women under 30.

As for safeguards. Well we have safeguards in place for disabled adults and children and you only have to look at the news to find multiple failures and abuse. For adults with learning disabilities 42% of deaths are considered preventable.

The often touted Oregon example is actually of extreme concern if you look more deeply. When it was enacted only 28% had a psychiatric assessment, now only 1%. The number of conditions has widened. In addition to cost of care a very large percentage are being culled because they feel they are a burden. A state which is very easy to manipulate in a vulnerable person. Once the annual summary has been done all data is destroyed. There is no follow up scrutiny.

https://livinganddyingwell.org.uk/oregon-death-with-dignity-act-access-25-year-analysis/