‘The crisis consists precisely in the fact that the old is dying and the new cannot be born; in this interregnum a great variety of morbid symptoms appear.’ —{Antonio Gramsci}

If Helen of Troy was the face that launched a thousand ships then the Gallagher brothers getting the band back together is the story to launch a thousand discourses. The monobrowed Mancunians have provided us all with an excuse to pontificate on an array of tangential topics, including nostalgia about the 1990’s in general, and more specifically New Labour, Britpop and cool Britannia, not to mention the changing nature of social class in Britain, the Irish diaspora, Manchester, and its cultural significance, how music is consumed, both live and in recorded form, masculinity, and a myriad of other topics. Given that Oasis were not an insignificant part of my own teenage years, this is a bandwagon that I am only too happy to clamber upon in order to utilise as a lens via which to view and also to discuss the topic of cultural stagnation.

WHAT WE TALK ABOUT WHEN WE TALK ABOUT BRITPOP

Whenever the band Oasis are mentioned in the mass-media then you can be guaranteed that the word ‘Britpop’ will never be far behind, even though it is not a term that has ever been used by Oasis themselves, nor is it a term that has ever been in common usage among their legion of fans, so what is actually meant by the term ‘Britpop’? In its most prosaic sense, it's a portmanteau term to denote British pop music but that doesn't really tell us much given that any music which is both popular and British, in the broadest sense, constitutes British pop music.

Britpop is a misnomer given that it's a reference to a type of alternative rock music rather than what we commonly refer to as pop music—i.e commercialised and formulaic, record-company manufactured chart-music aimed at teenage girls. Furthermore, aside from a few exceptions, Britpop is a reference to a collection of English bands with a distinctly English outlook, rather than a reference to music from Britain as a whole. Simply put, Britpop is a style of English alt-rock that emerged in the 1990’s, of which Oasis was the most famous and popular exponent.

From the Velvet Underground onwards, alt-rock has defined itself by its independent ethos, which was both rooted in economics, smaller record labels, and in its musicality, greater freedom for artistic experimentality. Rock music more generally emerged in the 1950’s from the American deep south and was the musical equivalent of the wider desegregation taking place in Jim Crow America at that time. This new musical hybrid created from the melding of country music with blues then became the soundtrack of the social, cultural and political convulsions of the 1960’s. The fact that rock music became the soundtrack of the 1960’s, and the baby boomer generation who grew up in that period, cemented its status as counter-cultural and subversive. If rock music more generally represented youthful experimentation and artistic freedom then alt-rock was essentially rock-squared. If rock music meant revolution then alt-rock was its revolutionary vanguard.

Britpop, like Grunge in America—which was a hybrid of heavy metal and punk but with an indie aesthetic—was alt-rock made by the generation (born between 1965 and 1980) that followed the baby boomers, dubbed Generation X. A generation who had absorbed the rock music of the 1970’s and 1980’s, in addition to the 1960’s canon. Second generation alt-rock, or Gen X alt-rock, took underground rock imusic on the pop-cultural fringe and made it part of the canon of classic rock, collapsing the distinctions between alternative rock and the popular mainstream.

Additionally, 1990’s British Gen X alt-rock, i.e Britpop, was essentially a revivalist movement which rejected the vast majority of the music of the 1980’s, with its synths and Kraftwerk influences, and which instead valorised the music of the 1960’s, especially The Beatles, but also The Kinks and The Small Faces. In so doing, rock music was transmogrified in the space of a generation from being a form of music on the cultural vanguard to being a form of music akin to folk-music or country-music with its own tradition, archive, curators, canon and ancestor worship. Inverting what rock music, alt-rock especially, had originally stood for—symbolised by The Who singing ‘I hope I die before I get old’ in ‘My Generation’—thereby killing it in the process. Rock music was meant to be subversive and counter-cultural but soon became the establishment culture that it had once railed against.

THE END OF (ROCK) HISTORY

The name of The Beatles is literally a homage to The Crickets and their Everly Brothers-inspired harmonies and Little Richard-inspired falsetto ‘woo’s’ are all a testament to their musical influences but in a very short period of time they were making music which was a radical departure from anything that anyone had ever heard before. From ‘She Loves You’ in 1963—tuneful and melodic, but of its time, Merseybeat pop— to ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’ in 1966—discordant, experimental, avant-garde, psychedelic, trippy space rock which sounded like a portal to the future and which still sounds futuristic today. Compare this to Britpop and Oasis. Oasis emerged in 1994 with Beatles-inspired harmonies, glam rock riffs, punk rock attitude, an aesthetic which drew from 1980’s football casuals and 1970’s mod-revivalist sub-cultures, a lead guitarist modelled on Johnny Marr, and a lead singer who was part John Lennon, part John Lydon, part Paul Weller and part Ian Brown. Fifteen years later, when they eventually split up, nothing much had changed. In a very short space of time, the levels of creativity that The Beatles exhibited went on an exponential curve. Whereas in their 15 year run, if anything, Oasis became less creative over time.

The musical trajectory of Oasis and of Britpop reflects the trajectory of rock music in general from the 1990’s onwards. Rock was a musical form which emerged in an explosion of creativity in the 1950’s and 1960’s but had finally exhausted itself by the 1990’s and ended up on the fast-track to a museum piece channelling the ghosts of yesteryear. Britpop itself wasn't so much a revivalist movement as a revival of a revivalist movement, like a photocopy of a photocopy in which the ink has faded over time. Oasis didn’t sound like The Beatles so much as The La’s sounding like The Beatles and they didn't look so much like 1960’s-era Lou Reed as Ian McCullough trying to look like 1960’s-era Lou Reed.

If Britpop wasn't so much retro-rock as meta-retro-rock then their recently announced upcoming reunion represents meta-retro-rock squared. It says something about the extent of our cultural stagnation that in the 2020’s the reunion of a band from the 1990’s, who were themselves products of cultural nostalgia about the 1960’s, has managed to generate as much excitement and anticipation as it has (to the extent that it has been discussed in Parliament.) It would be as if George Formby returned to the stage in the 1960’s to reproduce his popular act from the 1930’s, itself with roots in the Edwardian music-hall tradition of his father, and generating more interest than The Beatles or The Rolling Stones in their 1960’s heyday.

CULTURAL STAGNATION

The sheer popularity of Britpop 2.0 is a sure sign of cultural stagnation but far from the only one. Cultural stagnation is not limited to Britpop revivals or even the anaemic state of contemporary pop music as a whole either—Oasis registered two albums in the top 40 UK bestsellers of 2022 and no new artists (of any genre) broke into the year’s bestsellers—but also infects all of the arts, all forms of mass-entertainment, and, indeed. all aspects of society. To quote Paul Skallas: ‘Culture is frozen. Throughout the 20th century we had changes almost every decade. Changes in fashion, in music, in aesthetics, hairstyles, style of comedy, television shows and movies.’

The last genuinely subversive youth counter-culture was the rave culture that was ruthlessly suppressed by John Major’s Conservative government and then co-opted, commercialised, and domesticated by club culture a full thirty years ago. There used to be so many musical subcultures in this country (Suedeheads anyone?) and the growing identification with various Psychiatric/Neurodevelopment diagnoses /sexualities/genders among so many young people is, I suspect, a poor substitute for the sense of belonging/self-expression/identity that were once provided by these older musical subcultures. ‘Neurodiversity,’ for instance, isn’t so much a scientific term as an activist one, and serves as a placeholder for subcultural identities to form in the lacuna created by the absence of the types of musical subcultural identities that were formed and were commonplace in the late-20th century.

A good indicator of the extent to which pop-cultural churn has slowed to a standstill is the sheer longevity of 1980’s-retro. Notably, the most streamed song on Spotify (i.e Blinding Lights’ by The Weeknd) is a piece of 1980’s-retro. A large part of the appeal of ‘The Wedding Singer’ (1998) was its 1980s retro theme. It's now 26 years later and we’re STILL watching shows (‘Stranger Things’ being the best example) with an 1980s retro-theme. The 1980s lasted for only one decade (tautology klaxon) but 1980’s-retro has now lasted for 26 years and counting and it's not because we especially love the 1980’s, it's simply because that's the last decade which feels qualitatively different to our own. There have been attempts at post-1980’s retro, such as the films ’Turning Red’ and ‘Saltburn’ (both set in the 2000’s,) but they ultimately fall flat because the 2000’s are not different enough from our own time period in its particulars for the period details to be interesting.

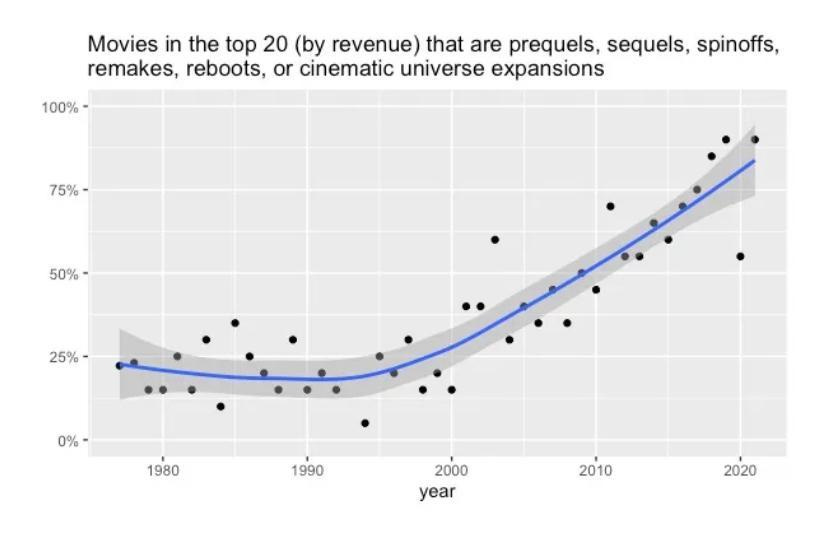

Wherever you look, signs of cultural stagnation abound. Cinema being the most obvious example. Cinema now means endless sequels, prequels and film franchises, and even new films like The Joker (itself a prequel) are basically homages to classic films from the 1970’s (Taxi Driver) and the 1980’s (King of Comedy.) In 2016, half of the Top 50 movies released were a remake or a sequel representing a 312 percent increase since 2000. The last time three non-sequels were the highest-grossing films of the year worldwide was in 2001. Comedy is another example, so-called alternatIve comedy, like alternative rock, quickly became establishment comedy, and every bit as tired and formulaic, whilst comedy shows like ‘Have I Got News For You’ and ‘The Simpsons’ linger on for decades, well past their sell-by date, like the ruins of an ancient civilisation.

RETROMANIA

Nor is cultural stagnation new to the 2020’s either. ‘Retromania: Pop’s Culture Addiction to its Own Past’ by Simon Reynolds, a book which focused upon the dearth of new ideas in 2000’s-era pop music, was written 13 years ago but could quite easily be published today because its punches still land squarely on our nose. Reynolds points to digital technologies as being one factor:- ‘The young musicians who’ve come of age during the last ten years or so have grown up in a climate where the musical past is accessible to an unprecedentedly inundating degree. The result is a recombinant approach to music-making that typically leads to a meticulously organised constellation of reference points and allusions, sonic lattices of exquisite and often surprising taste that span the decades and the oceans. I used to call this approach ‘record-collection rock’, but nowadays you don’t even need to collect records any more, just harvest MP3s and cruise through YouTube. All the sound and imagery and information that used to cost money and physical effort to obtain is available for free, just a few key and mouse clicks away.’

THE DECADENT SOCIETY

Ross Douthat, in his book ‘The Decadent Society - How We Became the Victims of Our Own Success’ situates cultural stagnation in a wider context of societal decadence, which he defines thusly:- ‘Decadence, deployed usefully, refers to economic stagnation, institutional decay, and cultural and intellectual exhaustion at a high level of material prosperity and technological development. It describes a situation in which repetition is more the norm than innovation; in which sclerosis afflicts public institutions and private enterprises alike; in which intellectual life seems to go in circles; in which new developments in science, new exploratory projects, underdeliver compared with what people recently expected. And, crucially, the stagnation and decay are often a direct consequence of previous development. The decadent society is, by definition, a victim of its own significant success.’

Douthat identifies the moon landings as a cultural turning point:- ‘I suspect that a truly globalised civilization cannot help tending toward decadence so long as it remains earthbound, so long as there is no hope of finding actual new worlds to leap toward, conquer, or explore. I suspect that what we see happening in our society today—the turn toward simulations and virtual realities; the declining birthrates; the sense of repetition, stagnation, and futility—is connected on a deep level to the post-Apollo mission sense that such a hope does not exist, that there is quite literally nowhere else for mankind to go, that we are stuck here waiting to either destroy ourselves accidentally or to have nature hit reboot, via comet or a plague, on our entire up-from-hunter-gathering, east-of-Eden project.’

The Douthat thesis is basically an extension and an update on ‘the frontier thesis’ advanced by the American historian Frederick Jackson Turner in the 1890’s, which posited that the Westward expansion of the USA created a distinctly American sensibility and mindset (subsequent borne out by research) which was conducive to achieving great things. The frontier thesis is interesting and is essential to an understanding of American culture and history but cultural stagnation, as we’ve already established via an analysis of Britop, isn't just an American phenomenon and therefore the Douthatian frontier thesis doesn't explain the transnational nature of cultural stagnation. The emphasis that Simon Reynolds places on digital technologies doesn't explain why cultural stagnation pre-dates the emergence of digital tech either. So what are the other causes? Well, there are a number of suspects.

GERONTOCRACY

{source}

The forces which underpin cultural stagnation are not limited just to pop music nor to pop-culture in general either. In my own sector, i.e mental health services, the same pharmacological and psychological treatments which predominated twenty years ago when I first started—SSRI’s, atypical antipsychotics and cognitive behavioural therapy—are still the therapeutic mainstays twenty years later. In politics, the paucity of new ideas are demonstrated by the likes of Liz Truss cosplaying as someone, Margaret Thatcher, who first became a Conservative MP in 1959, a full 65 years ago, and Donald Trump recycling an old Reaganite campaign slogan from nearly half a century ago, ‘Make America Great Again,’ which was itself a nostalgic lament for a previous era.

In the economic sphere, signs of stagnation abound, especially in the UK. In Great Britain, real wages grew by 33% a decade from 1970 to 2007, but have flatlined since, and the current productivity slowdown in the UK is the worst in the last 250 years. The NYT reported last year that the UK’s per capita GDP is 8.4 percent below its 2007 peak, which has helped make the country outside of London poorer than Mississippi. Whilst the IFS recently reported that the last Parliament was the worst for income growth for over 60 years. To top it all off, The Telegraph reported this year that people in their 30s are the first generation to earn less than those born 10 years before them since the 1930’s.

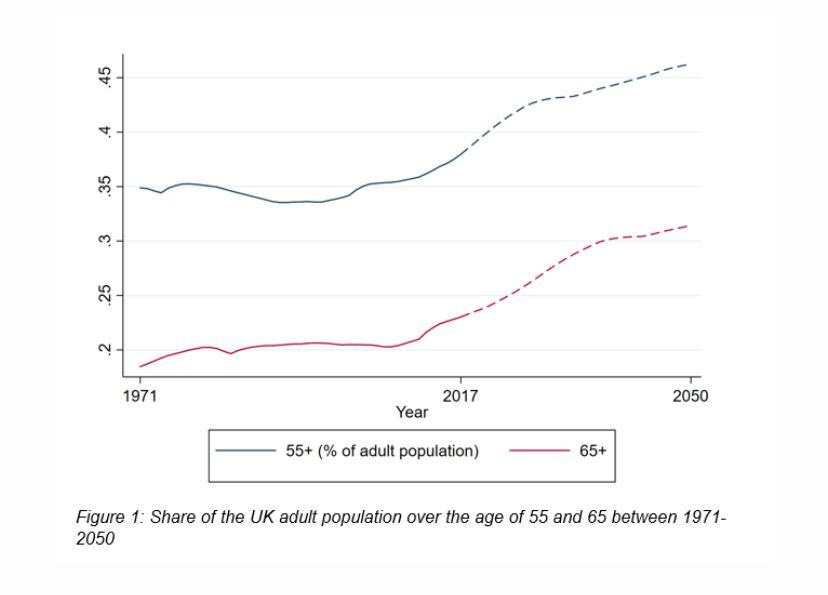

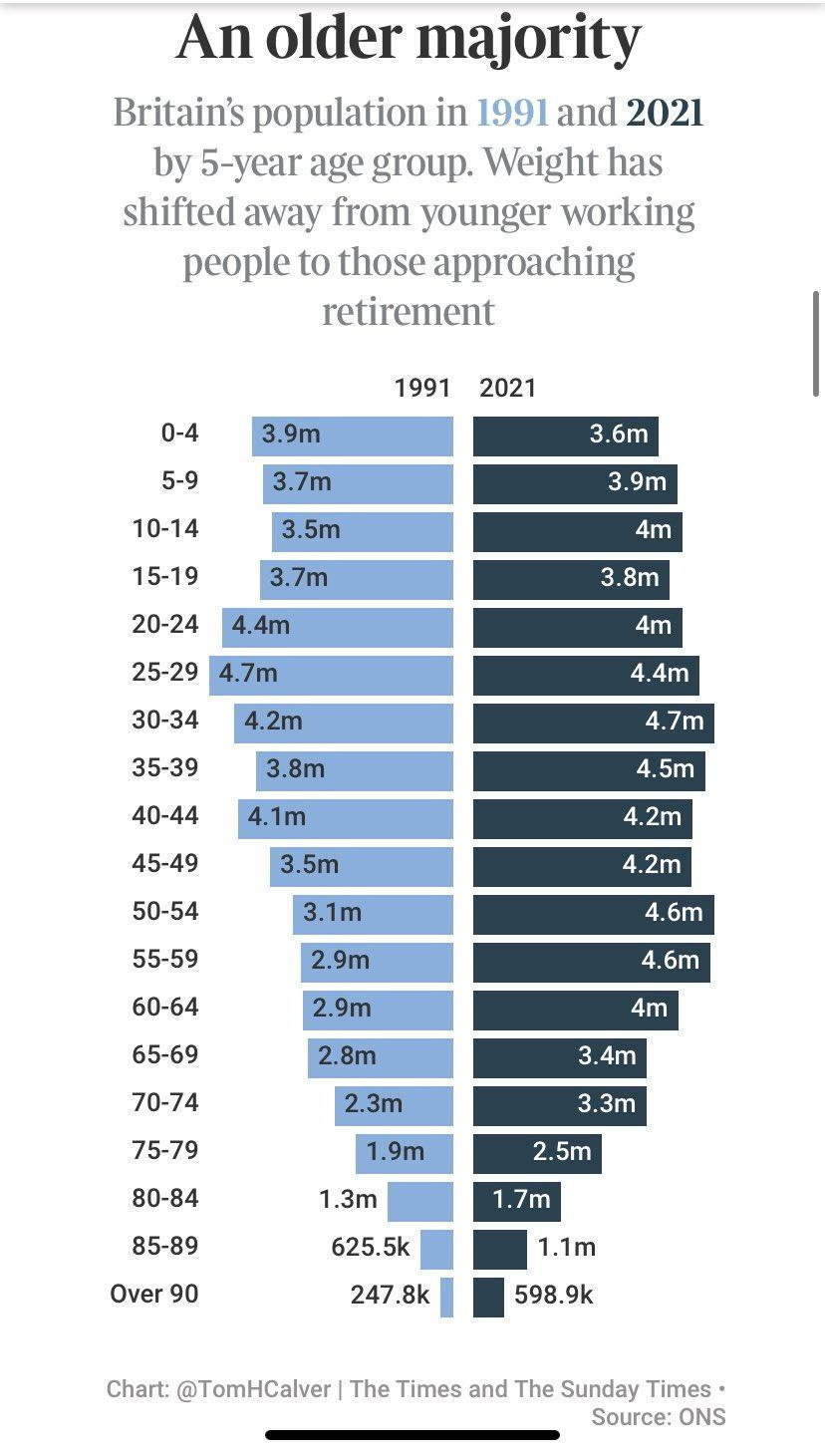

Britain’s economic stagnation is rooted, in large part, in the fact that we don't build anything anymore, whether that be reservoirs, nuclear power stations, houses, trams, or much of anything else for that matter. This NIMBYism may simply be a reflection of our planning system but given that NIMBYism isn't just a British problem then one wonders whether there is a wider/deeper factor at play. One likely suspect is the ageing of our society—by the end of 2026, the UK will have more people aged 65+ than under 18 for the first time in its history—because this is a common factor which pertains to all of the countries in which NIMBYism is a problem.

{source}

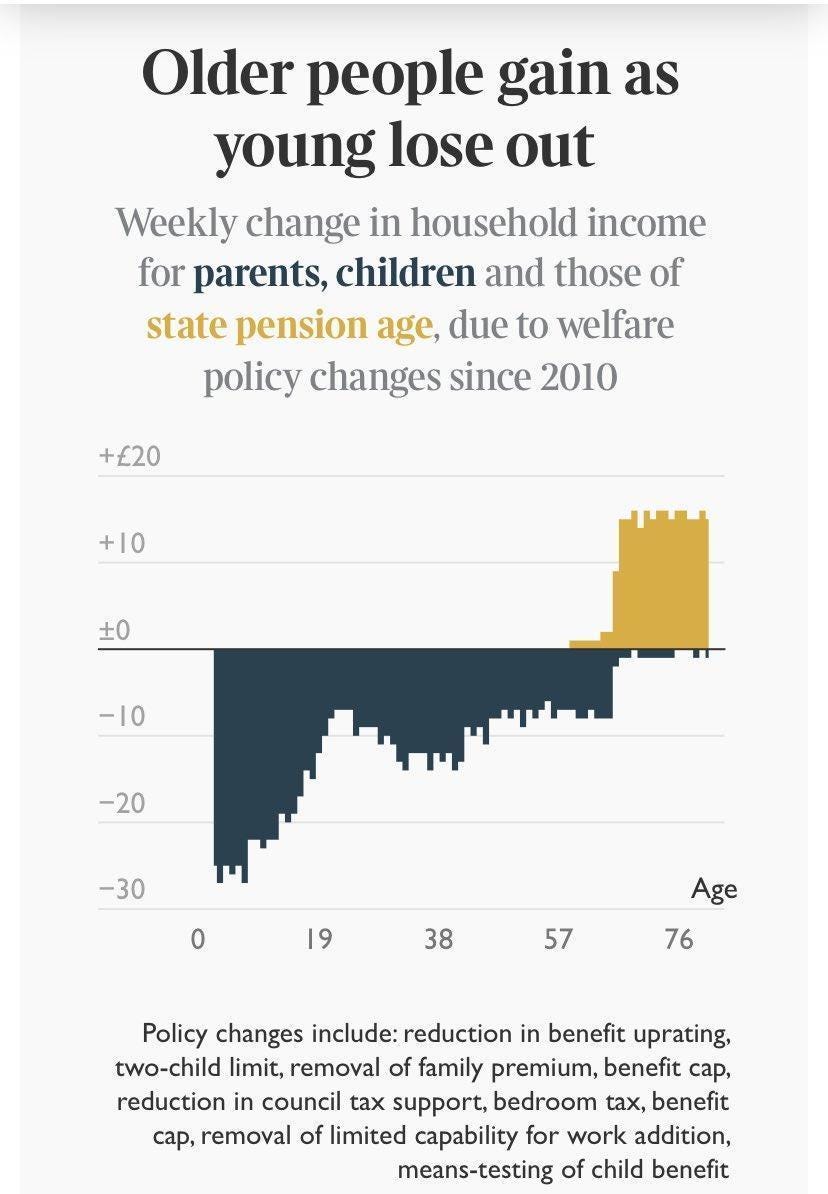

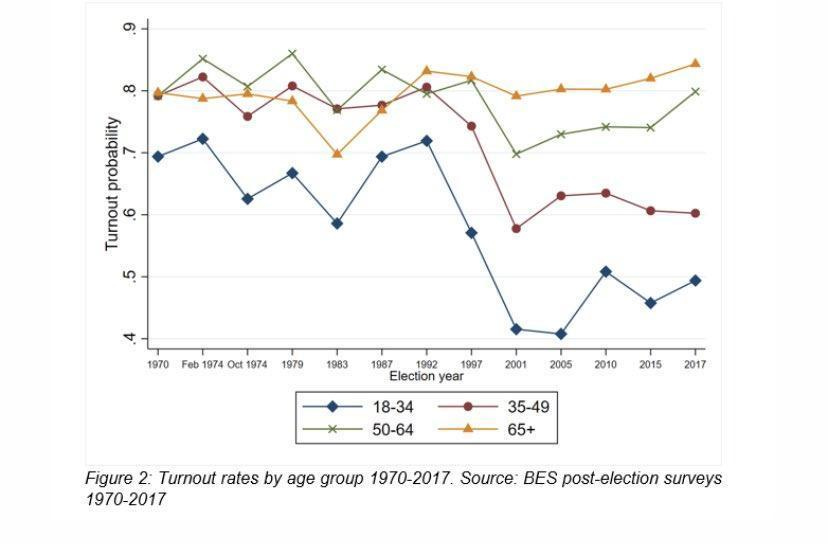

Ageing societies risk becoming gerontocracies which are run for the benefit of the older generation but paid for by the young. At the last general election in Great Britain the incumbent party’s offer to young people was literally mandatory national service whilst its offer to older people was additional gold-plating of pensions which already make up 42% of our total welfare budget. The Telegraph reported earlier this year that the ’share of the UK aged over 65 rose from 14% in 1974, to 16% in 2004, to 19% in 2022., by 2070, it will be closer to 30%…as younger residents are more likely to be immigrants, members of older generations are more likely to be eligible to vote…those aged over 55 will constitute a majority of votes cast in this year’s election..likely the majority of votes cast in a majority of constituencies too.’ Whilst The Spectator reported in 2022 that ‘Voters over the age of 55 make up an outright majority of the voting public..the ageing population means the number of pensioners is set to increase 28% by 2045….Older societies accordingly tend to eschew capital spending in favour of current consumption.’

{source}

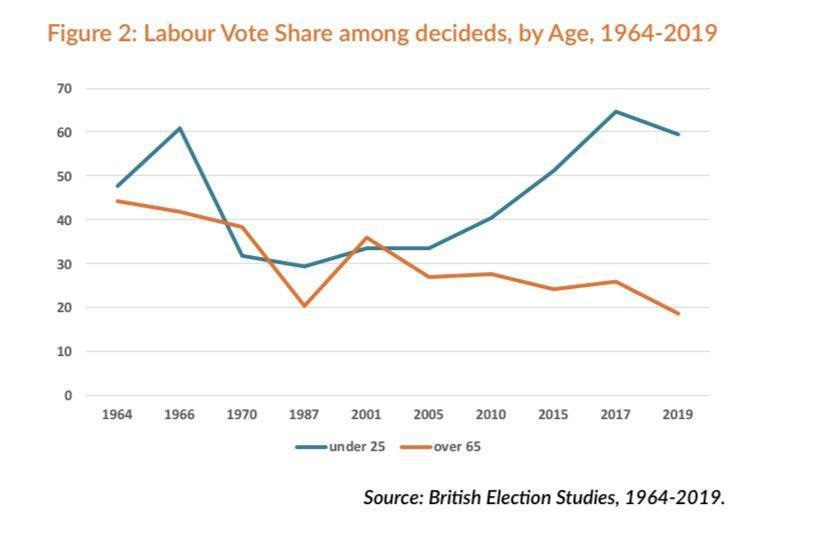

Gerontocracies are problematic for a number of reasons. Age-related political polarisation being one. Political scientist Ben Ansell has written, as regards the British context, ‘generations have always voted slightly differently. Back in the 1980s and 1990s, there was about a ten point difference, with older generations more Conservative. But the last decade or so has seen a massive widening of generational divides.’ In 2022, The Times reported that:- ‘Less than 38% of over-65s voted Tory in 1997, compared with 59% in 2019.’ Whilst the FT reported in 2023 that:- ‘In the 2019 election, Labour won 88 seats in which over a quarter of the population was aged between 18 and 34. The Conservatives won just 16 — but they took 65 seats where more than a quarter of the population was 65 or older. Labour won two.’ In 2023 The Times reported:- ‘As recently as the 1983 general election, the Tories led Labour by nine percentage points among 18 to 24-year-olds, and by 11 points among 25 to 34-year-olds. But by the 2019 election, Labour led by 43 points and 24 points respectively’

{source}

As well as age-related political polarisation, gerontocracies influence economic policies too and not necessarily for the better. To quote Tim Vlandas—in ‘From Gerontocracy to Gerontonomia: The Politics of Economic Stagnation in Ageing Democracies’—‘‘In a democracy dominated by grey voters (gerontocracy), electorally viable policies lead to an economy that is reorganised to prioritise the socioeconomic needs of the elderly, namely good pensions, and low inflation, over a commitment to economic growth….Older people have an incentive to favour lower inflation, even at the expense of higher unemployment, because they derive income from savings, housing, or other financial assets rather than labour income. In addition to favouring lower inflation, the elderly are also less directly affected by lower economic growth and recession, unlike younger and middle-aged individuals who rely on work-related earnings as their main source of income.’

{source}

These insights are borne out by the UK statistics. One in four pensioners is a millionaire, whilst the median pensioner already has more disposable income than the median worker, and is likely to have greater wealth. People in their sixties are much more likely to have more than £1 million in assets than any other age group. 50-64 year olds now own 78 percent of the UK’s private housing wealth. The over-65’s in the UK own £2.587 trillion in housing wealth, whilst 41% of 20 to 34-year-olds have no property wealth. For those over the age of 55, the average household wealth is around £511,000. For those aged between 25 and 34, the figure is £198,100. For those between 25 and 34, it is just £76,800 - barely 15% of the average over 55 household.

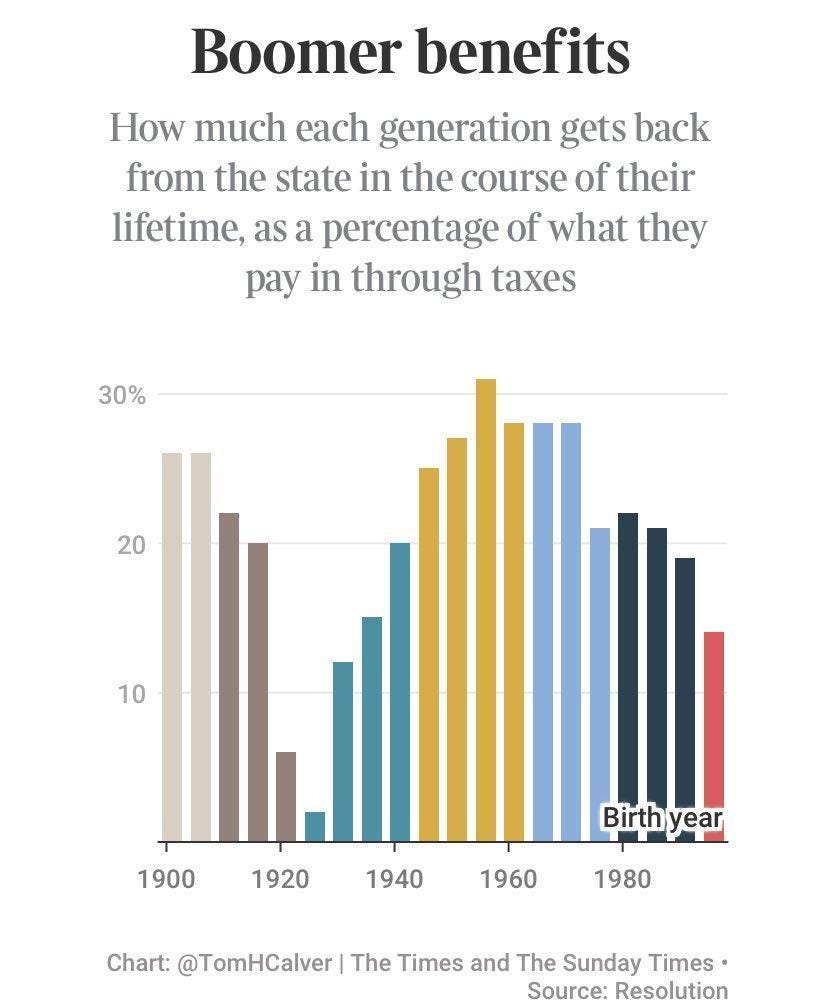

Whilst The Times reported last year that ’researchers from the Resolution Foundation think tank added up all of the benefits, pensions and healthcare paid to each generation born in the 20th century, then subtracted the taxes they had paid. The result is that people born between 1956 and 1960 are the biggest beneficiaries of the lot, withdrawing about 31 per cent of the money they put into the state. By contrast, those born between 1996 and 2000 are expected to withdraw just 14 percent of what they pay in, assuming policies continue as they are.’ On average someone born in 1956 will pay about £940,000 in tax throughout their life. But they are forecast to receive state benefits amounting to about £1.2m, or £291,000 net. Someone born in 1996 will enjoy less than half of that figure. In 2018-19, the government spent roughly £14,655 for each child in Britain, £10,178 for each working age adult, and £20,789 for each pensioner.

{source}

AND BACK TO CULTURAL STAGNATION

Ok, what does all this have to do with cultural stagnation you may ask? It demonstrates that cultural stagnation and economic stagnation are very likely to be two sides of the same coin with the same root causes. Cultural stagnation is an international phenomenon and therefore nation-specific explanations are likely to be incomplete in their accounting for it. One factor that does fit the international nature of the problem, and also its timing, is the ageing of many of our societies.

Due to a combination of falling fertility and increased life expectancy, globally. the number of people older than 80 is expected to increase sixfold by 2100. Meanwhile, the population of children 5 and younger will get halved. Proportionally fewer young people means proportionally fewer new ideas because younger people are simply more likely to generate them.

The Economist reports that; ‘Younger people have more of what psychologists call “fluid intelligence”, meaning the ability to solve new problems and engage with new ideas. Older people have more “crystallised intelligence”—a stock of knowledge about how things work built up over time. There are no precise cut-offs, but most studies suggest that fluid intelligence tends to peak in early adulthood and to begin to decline in people’s 30s….In the long term, it is only by raising productivity that standards of living can be lifted. Demographic decline will chip away at that contribution over time by reducing the number of novel ideas stemming from the fluidly intelligent minds of young workers…..Some researchers believe such a demographically driven reduction in innovation is already under way in parts of the world. James Liang, a Chinese economist and demographer, notes that entrepreneurship is markedly lower in older countries: an increase of one standard deviation in the median age in a country, equivalent to about 3.5 years, leads to a decrease of 2.5 percentage points in the entrepreneurship rate.’

Furthermore, ageing societies risk becoming gerontocracies characterised by economic stagnation, which is then mirrored in its pop-culture. Hence, endless sequels, prequels, remakes, franchises, spin-offs, reformations and revivals, all of which are hallmarks of a widespread cultural stagnation.

Ageing societies are less creative because, as Ross Douthat put it; ‘societies without many young people are simply less likely to be dynamic, less interested in risk taking, than societies with younger demographic profiles.’ An insight borne out by the available research on this matter.

{source}

URBANISATION AS A DRIVER OF CREATIVITY

Ageing societies do not simply have fewer young people but also fewer young people in the right places too. As Ted Gioia has written; ‘Epicentres of musical innovation are always densely populated cities where different cultures meet and mingle, sharing their distinctive songs and ways of life. This intermixing results in surprising hybrids.’

A cursory glance at the history of popular music over the last century and a half bears this out. Jazz came from New Orleans, rock from Memphis, hip hop from New York, while Seattle, Chicago, Detroit, Berlin, Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and London also made singular contributions. What they all share in common is the fact that they are all large metropolitan conurbations with lots of young creative people in them.

City residents, according to Edward Glaeser, are 19 percent more likely to go to a rock or pop concert, 44 percent more likely to visit a museum, and 98 percent more likely to go to a cinema. Big cities are not just drivers of economic growth then but also engines of creative experimentation. It's not just more young people that we need but also more young people in the right places. New ideas are more likely to come from young people but those ideas are more likely to come to fruition when they are embedded in a wider social network conducive to their dissemination i.e big cities. Given that it is now prohibitively expensive for young people to live in cities like London and Manchester it is therefore no surprise that we are both creatively and economically stagnant as a country.

NOSTALGIA AIN'T WHAT IT USED TO BE

None of this is to say that a Britpop revival is a bad thing, I myself am an Oasis fan and have been for thirty years—I was 14 when Definitely Maybe came out, and 15 when What's The Story Morning Glory was released, so I was the perfect age to become an Oasis fan and did become so, buying all their albums plus seeing them live three times in the early 2000’s— but an Oasis regenesis in the 2020’s does bring into sharp focus the extent to which we are free-riding off the creativity of yesteryear. Nostalgia isn't inherently bad, in fact there is plenty of evidence to indicate that it is psychologically healthy, but we appear to be stuck, both culturally and economically, in an endless retread of the past, seemingly unable to imagine alternatives to the current economic and cultural mainstream consensus. Which is certainly not healthy for our culture or our economy.

Much of this is about the technological changes in the 20th century that allowed for new sounds, new fashions. You don't get the miniskirt without elastane being invented, so women can wear tights rather than stockings.

And many industries just run out of innovations. The design of the bicycle was about done in 1930.

The most exciting things right now, culturally are probably tiktok and YouTube. It's what is the teenage thing. It's democratised filmmaking and distribution and all sorts of things are being created.

Charlie Brooker once said the only art form still evolving is video games. And that was more than a decade ago now. Not a gamer so can't comment about those, but it struck me as essentially true, and getting ever truer. No one is a bigger fan of 90s Simpsons or HIGNFY than me, but how are they both still going in the 2020s?! Nothing is allowed to just die anymore.

Now it can't possibly be the case that music as a whole has reached its full stop. Yet it does seem like a long time since we had a truly original new sound. Tbf, I'll concede that this is a very Western-centric lament.

And besides, I'm not a music buff. All the tunes/bands I like have come to me second hand through films, TV shows etc. Yet in those mediums too, there has been minimal innovation of late. For example, a typical edition of MOTD in 2024 is almost identical to one from 2004. Yet go back another 20 years to one from 1984 and it's barely recognisable - and one from 1994 in between is very different to either - apart from the theme tune of course. Same goes for fashion and clothing.

So many factors responsible for it all. Gonna have to read those books you recommend. John Higgs' book on the KLF briefly touches on this theme as well (amongst many others - I'm particularly taken with his view that the early 90s was a strange untethered nowhereland, after the Cold War but before the information age). I might suggest that Dummond & Cauty and the acid/rave scene is the last proper counter-cultural movement.