FIERCE COMMUNITARIANISM - The Social Recession and its Discontents

‘Strange how people who suffer together have stronger connections than people who are most content’ (Bob Dylan, Brownsville Girl.)

INTRODUCTION

There are a number of trends that can be knitted together under the heading of a ‘social recession,’ or a ‘loneliness epidemic,’ which features more people spending longer periods on their own instead of engaging with others in social settings face to face. In this blog I'm going to delve into some of the statistics that highlight this phenomenon, analyse which factors have contributed towards its occurrence, consider what relevance it may or may not have to broader worries, such as mental health concerns, and then try to answer the question of why I think it matters.

BOWLING ALONE

Anyone who writes on the topic of a ‘loneliness epidemic’ or a ‘social recession’ is standing on the shoulders of Harvard political scientist Robert Putnam who wrote the data-rich, zeitgeist-capturing, social science bestseller ‘Bowling Alone’ 25 years ago. Putnam coined the term ‘social capital’ to explain why the collapse of associational life in America from the 1960s onwards mattered, not just in terms of personal misery, but also for broader societal trends which underpin the functioning of advanced democracies, such as declining social trust and civic engagement. Putnam, in turn, built on the work of sociologists, such as Emile Durkheim, writing in the 19th century, who demonstrated that deeply personal acts, such as suicide, followed predictable patterns linked to wider societal differences between Catholic regions—more communal and with lower suicide rates—and Protestant regions—more individualistic and with higher suicide rates. You could go further back to the 17th century and to Robert Burton who summarised his mammoth ‘Anatomy of Melancholy’ by advising his readers to ‘be not solitary, be not idle.’

I situate my own thoughts on this subject in this historical context not to compare myself to the likes of Putnam, that would obviously be silly, but to demonstrate that modern-day concerns about a ‘social recession’ have an older lineage. This is important to emphasise because there is an increasing tendency to blame every societal problem on smartphones and social media in an all-encompassing theory of everything. As well as being intellectually lazy this tendency veers towards being ahistorical as it ignores the fact that many of these trends have their roots in earlier historical periods.

LIQUID MODERNITY

Indeed, my own conclusion about the problem of declining social capital is that atomisation is baked into the cake of modernity. I do not believe that it has emerged simply with the advent of the smartphone or because of the Covid Pandemic. Louis Menand (in his book The Metaphysical Club) described modernity in these terms:- ‘Modernity is the condition a society reaches when life is no longer conceived as cyclical. In a premodern society, where the purpose of life is understood to be the reproduction of the customs and practices of the group, and where people are expected to follow the life path their parents followed, the ends of life are given at the beginning of life. People know what their life's task is, and they know when it has been completed. In modern societies, the reproduction of custom is no longer understood to be one of the chief purposes of existence, and the ends of life are not thought to be given; they are thought to be discovered or created. Individuals are not expected to follow the life path of their parents, and the future of the society is not thought to be dictated entirely by its past. Modern societies do not simply repeat and extend themselves; they change in unforeseeable directions, and the individual's contribution to these changes is unspecifiable in advance. To devote oneself to the business of preserving and reproducing the culture of one's group is to risk one of the most terrible fates in modern societies, obsolescence.’

{link}

Modernity then represents the freedom for the ordinary man and woman to chart their own course in life free from the weight of constraints placed upon them by traditional hierarchical societal structures, but it's important to recognise that this freedom is built upon a shared and broad-based peace and prosperity that has been bequeathed to us by the economic transformations of the last 250 years or so, it hasn't arisen in a vacuum. This freedom, in the context of the entirety of human history, is a privilege that has, up until very recently, only ever been accorded to a select few. Whereas real communitarianism in contrast arose out of socio-economic conditions in which people had relied upon each other out of sheer necessity because of the harsh and precarious exigencies of life.

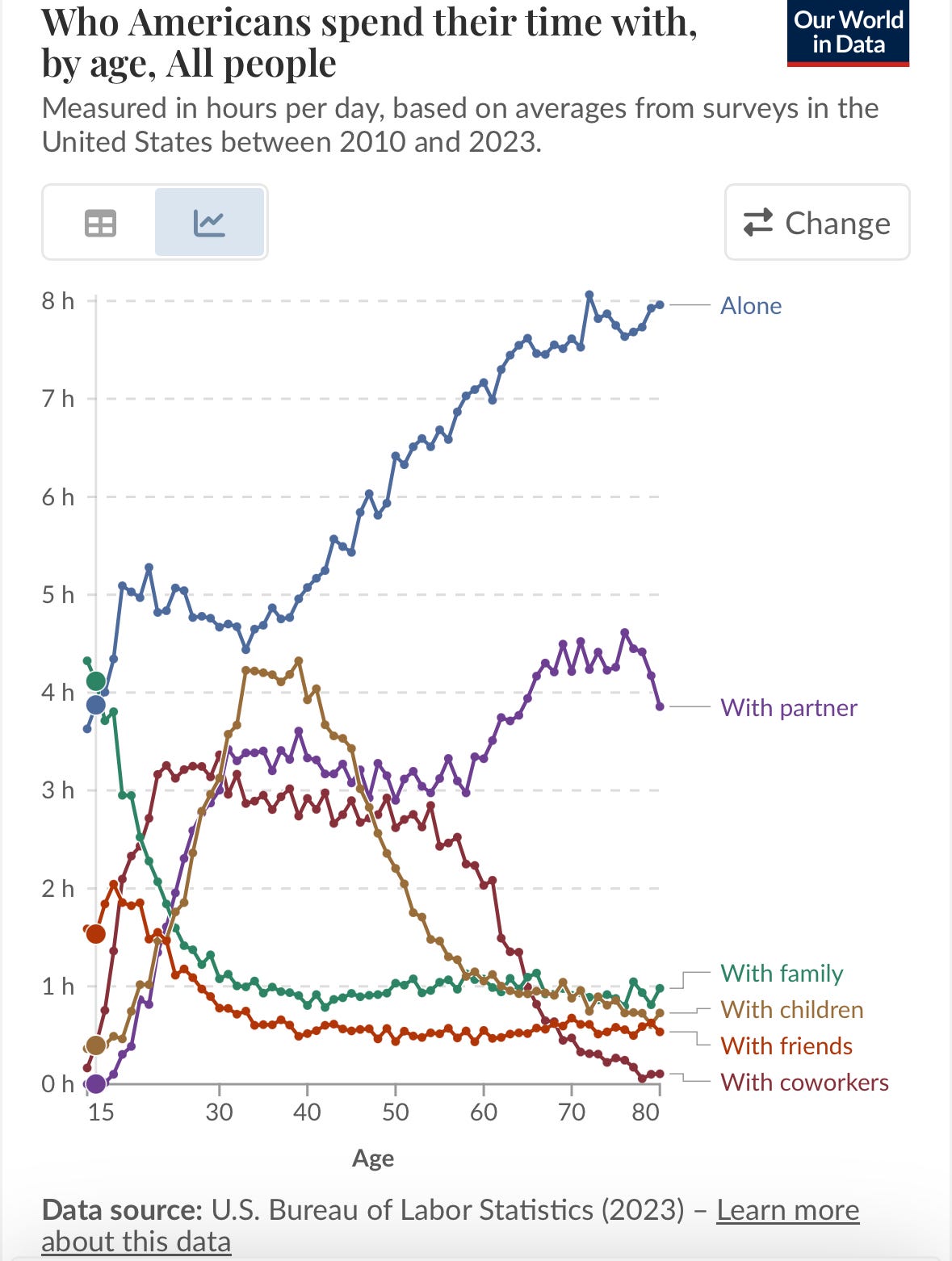

In other words, real communitarianism is not happy-clappy, lovey-dovey, peacenik communalism, but rugged survivalism, and its antonym, modern atomisation, has occurred precisely because we no longer have to rely upon the protection of such close-knit communities in order to survive. In the hierarchy of human needs, security comes first before self-actualisation and now that the impersonal forces of our shared broad-based peace and prosperity, combined with technological advances and the modern bureaucratic state, secures our survival, our relationships with others have increasingly become characterised by choice, rather than necessity, and we are increasingly choosing to spend less time with others and more time on our own. Associational life is subsequently withering on this vine.

THE SOCIAL RECESSION

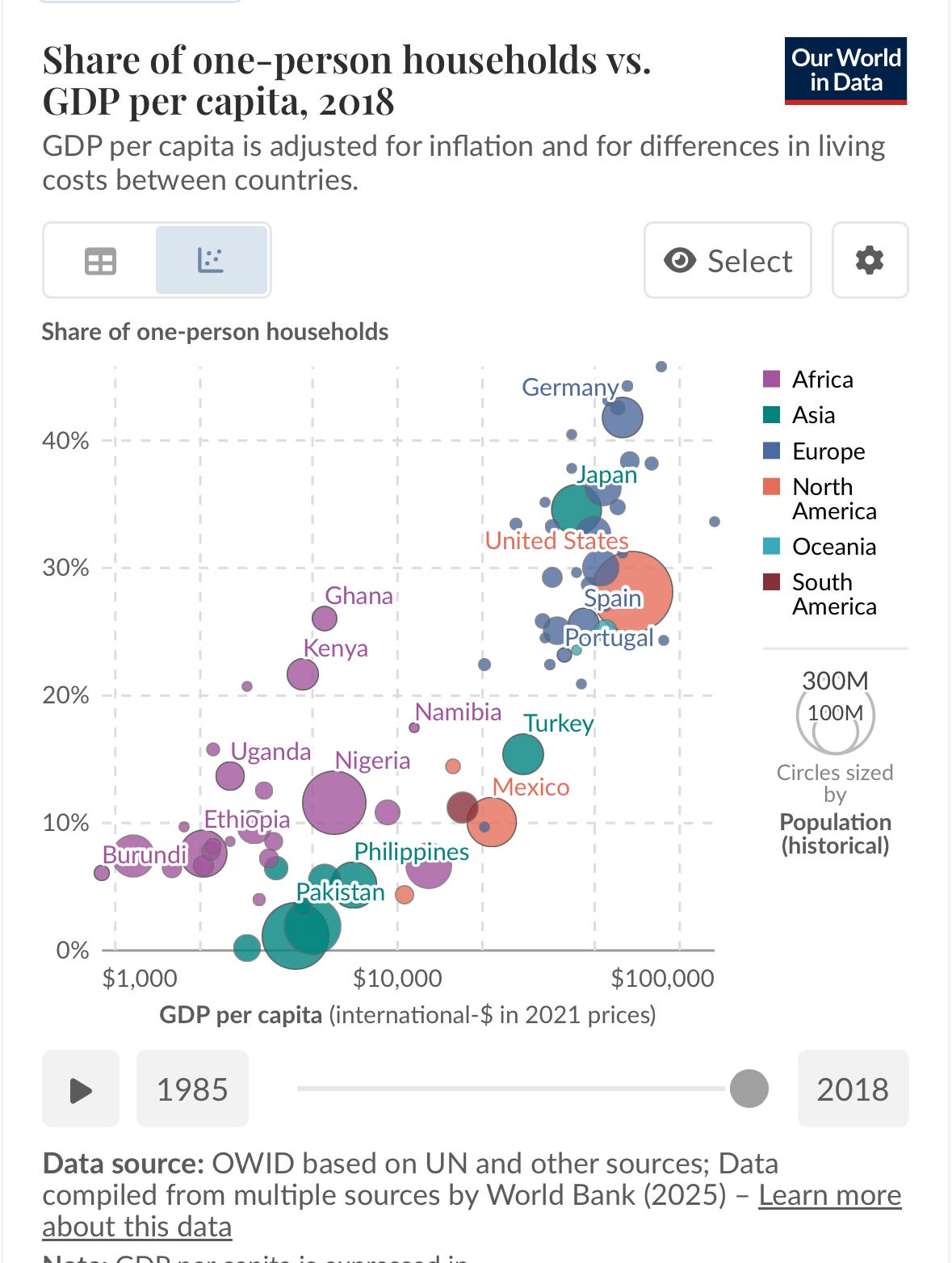

The statistics on this all point in one direction. In the UK, time with friends is down, the number of friends we have in the first place is also down, the number of people living alone has nearly tripled since 1971, fewer people are joining community groups, political parties, trade unions, going to church, pubs, nightclubs. we’re engaging less in volunteering, we’re also marrying less, and divorcing more. In the USA, you will find similar statistics, and in Japan, South Korea, Europe, and anywhere else you care to look with the standard features of modernity in place—i.e urbanisation, industrialisation, mass education and secularisation—you will find the same thing. It is telling therefore that before 1800 there wasn't even a word for loneliness in the English language.

The social recession falls most heavily upon men. As Robert Putnam wrote in Bowling Alone:- ‘Informal social connections are much more frequent among women, regardless of their job and marital status... Married or single, employed or not, women make 10-20 percent more long-distance calls to family and friends than men, are responsible for nearly three times as many greeting cards and gifts, and write two to four times as many personal letters as men…Women spend more time visiting with friends….women are more likely to express a sense of concern and responsibility for the welfare of others — for example, by doing volunteering work.’

{link}

In America, the percentage of men with at least six close friends has fallen by half since 1990, from 55% to 27%. Whilst the percentage of men without any close friends jumped from 3% to 15%. The male social recession has gone hand in hand in the decline of marriage as it is unmarried men who are disproportionately more likely to be socially isolated. Studies have demonstrated that relative to men, women, on average, have closer social ties outside of their romantic relationships that often serve their needs for intimacy and, when needed, emotional support. This, in turn, creates stronger dependence in men on their romantic partners.’ The decline of marriage, and of the family life which accompanies it, has created a tranche of men who are increasingly asocial, as Derek Thompson has written:- Single men without kids—who have the most leisure time—are overwhelmingly likely to spend these hours by themselves. And the time they spend in solo sedentary leisure has increased, since 2003, more than that of any other group.’

ANOMIE

This male asociality approximates closely to Durkheim’s concept of anomie which results from the absence of strong social bonds and social cohesion. This concept was central to his study on suicide and why he felt it occurred with greater frequency in some societies more so than others. Suicide is overwhelmingly a male phenomenon and anomic suicide even more so. Suicide is more common among people in general who are single, who live alone, who are unemployed, who are not religiously observant. The bond that unites individuals with the group attaches them to life, is how Durkheim put it. However, whereas people who are divorced are more than twice as likely to die by suicide as married people *in general,* divorced men, *in particular,* are more than nine times more likely to die by suicide than divorced women.

Suicidologists, building on Durkeim’s concept of anomie, describe a ‘come together effect’ in which suicide rates drop during times of societal crisis, such as war or natural disasters, as people bond more tightly together.

As Sam Knight has written:- In the nineteen-fifties, the U.S. military, looking for insights into how to manage society after a nuclear attack, funded sociologists to analyse the ways that people behaved during large-scale emergencies. Instead of finding Hobbesian dioramas of disorder and panic…the sociologists discovered that, during a crisis, people often experienced deep feelings of solidarity and belonging. One of the researchers, Charles E. Fritz, had been a captain in the U.S. Army Air Corps during the Second World War. Afterward, he studied the impact of bombing on the German civilian population. “People living in heavily bombed cities had significantly higher morale than people in lightly bombed cities” he wrote.’

Crisis situations force people to become more pro-social. This leads to some slightly surprising statistics. After 9/11, divorce and suicide rates fell, after the Oklahoma bombing, fertility rates increased, in regions with more extreme weather events and that are more conflict-prone, you also see increased fertility. Suicide rates fell during both world wars, and fall during wars in general, suicide rates also decrease in regions that have had earthquakes, and also decrease during pandemics. During the last pandemic, charitable giving, volunteering, helping strangers and kind acts all increased.

FIERCE EGALITARIANISM

The come together effect provides a clue as to what circumstances underpin real communitarianism and it isn't peace and prosperity. For the vast majority of the history of our species the human animal lived as hunter-gatherers on the precipice of survival. Human culture evolved in that context and so much of what may at first seem puzzling about human behaviour is explicable in this light. Pair-bonding, cooperative breeding, religion, rituals, even music and dancing, all emerged as a means to bond us more tightly together because that was our greatest strength in the constant battle for survival. We are a social animal not because it's nice, warm and fluffy but because it was necessary for our survival. As James Suzman has written:- The kind of egalitarianism practiced by hunter-gatherers was not born of the ideological dogmatism that we associate with twentieth-century communism or even the starry-eyed idealism of New Age communalism.’ Anthropologist Richard Lee described hunter-gatherer egalitarianism as fierce egalitarianism to connote the way in which it actively policed.

{link}

Likewise, real communitarianism is also ‘fierce’ in the sense that it was first and foremost about survival and because pro-social behaviours relied on constant reinforcement by others. However, when material circumstances improved and peace and prosperity advanced, fierce communitarianism died with it. As Louise Perry has written:- ‘So why did these tight-knit communities fall apart? Historian Marc Brodie suggests that it comes down to simple economics: people got richer…the mutual help and cooperation seen as fundamental to these communities may have been in large part instrumentalist in nature. What appeared to be close, friendly relationships and freely given reciprocal aid seemed to mostly vanish as soon as economic circumstances improved and the poor no longer needed to rely upon each other for simple survival.’

Auron MacIntyre continues in the same vein:- ‘For most of history, individual independence was difficult, if not impossible. People relied on their communities for safety, food, education, goods, and entertainment. In many ancient societies, exile was tantamount to a death sentence. Some preferred suicide to being cast out. Reputation and honour mattered more than money because survival depended on others’ trust. A man’s worth reflected the number of relationships he had managed honourably over time. Today, people can meet most of their basic needs without relying on others.’

BE NOT SOLITARY

The economic rationale for fierce communitarianism no longer exists, at least in countries like the USA and the UK. However, because we evolved to live in close-knit social groups, the need to connect with others, and to belong to groups, still remains. The evidence is very clear: the more time we spend on our own, the more likely it is that we become anxious and miserable. Hence Robert Burton’s admonition to ‘be not solitary.’ To repeat, the evidence on this is very clear. Gatherings are an essential part of human functioning. Their relative absence from modern life has detrimental consequences to well-being. The more integrated we are with our community, the less likely we are to experience colds, heart attacks, strokes, cancer, depression, and premature death of all sorts. Loneliness triggers stress responses, impacting inflammation, metabolism, repair, and brain function. Just going from being friendless to having one friend or family member to confide in has the same effect on life satisfaction as a tripling of income.

CONCLUSION

The social recession, which underpins so many of our modern woes, is baked into the cake of modernity itself. Pre-modern societies are fiercely communitarian. In such societies loneliness doesn't really exist, even the word loneliness doesn't exist, and the idea of a loneliness minister would literally be incomprehensible. The social recession, in one sense, is an artefact of WEIRDness (in the Joseph Henrich sense) and is less common in less advanced economies. This makes the problem difficult to solve without running into a number of unintended consequences. However, given that the need to connect with others, and to belong to groups, remains etched in the human heart, we have no choice but to try. We evolved to live as social animals and that is what we continue to be.

‘The bond that unites individuals with the group attaches them to life’ (Emile Durkheim.)

Isn't this such an important subject... we desperately need to rebuild our communities. Interesting thoughts

Phenomenal writing. I couldn't agree more. I think the final image is rather apt too