ITS NOT THE PHONES

What matters most for children/adolescents is what happens in their offline worlds, at school, and, especially; at home

INTRODUCTION

In my last Substack post I took aim at the fashionable theory that there has been an epidemic of mental illness among young people caused by smartphones. Im not convinced that there has been an explosive increase in the true prevalence of mental illness and Im very much not convinced that smartphones/social media cause mental illness either, for reasons I explain in my last Substack post. This theory does not accord with my own professional experiences as a mental health practitioner of the last twenty years nor does it neatly match the research that is quickly accumulating on this topic either. Smartphones and social media are an international phenomenon but rises in the objective indicators of mental distress among young people have not been uniform everywhere and have shown much wider variation. In this piece I am not substituting another factor to explain a reported increase because I do not believe there has been an significant increase in mental health problems among young people (for reasons I explain in my last Substack post.) The same things that are linked to mental ill-health problems among young people in the current era are the same things that were linked to mental ill-health in the previous era. What matters most for children/adolescents is what happens in their offline lives, at school and especially at home. That hasn’t changed. That is the point of this piece.

There are a number of things that are actually associated with the mental ill-health of young people and, in my opinion, the most important of all pertains to the family context in which the young person finds themselves in. This clinical experience is also matched by an extensive evidence-base on the topic. My basic observation is that children raised in care have the worst mental health outcomes and what those children have in common is related to family context, not screen-time. What we see in more extreme form with respect to children raised in care is seen to a lesser extent in children/adolescents exposed to varying degrees of family conflict, dysfunction and breakdown. I wanted to take the opportunity in this post to explore these issues in more depth and to emphasise the importance of family structure and family functioning for child and adolescent mental health.

ADVERSE CHILDHOOD EXPERIENCES (ACE’s) AND THEIR LINKS TO MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

{source}

Family context is a hugely important variable when it comes to determining mental health outcomes because children raised by their married biological parents are less likely to be exposed to adverse childhood experiences. Adverse childhood experiences (ACE,) such as child maltreatment, a category which includes abuse, have repeatedly been found to have strong links to the mental health outcomes of children and adolescents. ACE’s result in an increased risk for mental health diagnoses across the lifespan, and are associated with a host of morbidity and mortality outcomes, a finding which has been replicated even when controlling for shared genetic and environmental factors, and which is particularly evident after multiple ACEs or sexual abuse. ACE’s have a strong and dose-responsive association with attempted suicide among adolescents and are also strongly associated with borderline personality disorder, a group who are thirteen times more likely to report experiencing childhood trauma. Childhood adversity is a transdiagnostic risk factor for psychopathology.

CHILDHOOD MALTREATMENT AND THEIR LINKS TO MENTAL HEALTH PROBLEMS IN CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

{source}

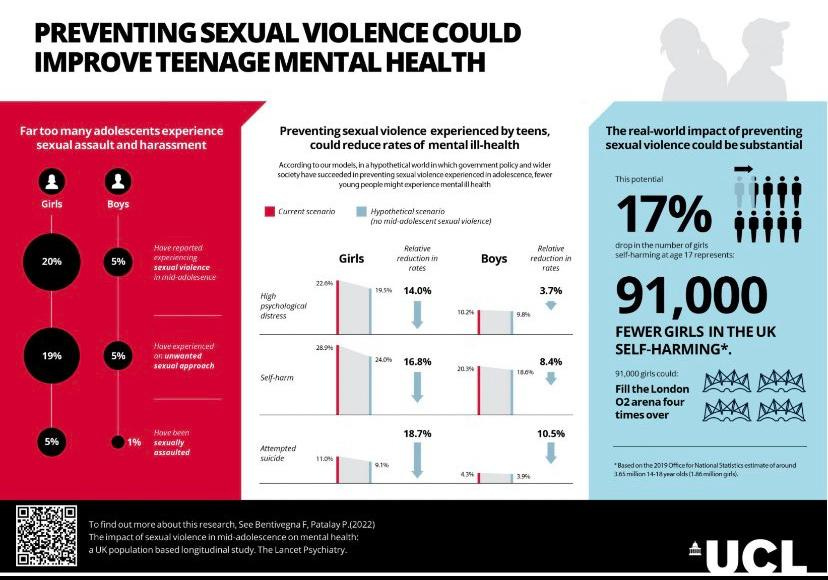

Child maltreatment (sexual abuse, physical abuse, emotional abuse and neglect ) arguably represent the most damaging forms of ACE’s. It is estimated that one in five adults in England and Wales have experienced childhood sexual abuse, and that 15% of girls and 5% of boys experience some form of sexual abuse before the age of 16, numbering up to half a million children every year. Other estimates indicate that girls are almost five times more likely than boys to experience sexual violence, which, some believe, is suggestive of the possibility that sexual assault and harassment could be an important driver of the gender gap in mental ill health that emerges in adolescence. In the USA, 16.1% of women and 6.2% of men reported a history of childhood sexual abuse. One study found that experiencing sexual abuse at any time before age 18 was associated with 9.3% greater likelihood of having been diagnosed with anxiety ever, 10.5% greater likelihood of depressive symptoms in adulthood, and 4.4% greater likelihood of recent health-or emotional-related absence in adulthood. A study by the UCL estimates that the prevalence of serious mental health problems among 17-year-old’s could drop by as much as 16.8% for girls and 8.4% for boys if they were not subjected to sexual violence.

All different types of childhood maltreatment including sexual abuse, physical abuse and emotional abuse, are associated with two-to-three-fold increased risk for suicide attempts. Sexual abuse in particular doubles the risk of suicide attempts according to some studies, whilst other studies estimate that the experiences of childhood sexual, physical, and emotional abuse were associated with as much as two-fold greater odds for suicide ideation and that sexual abuse was associated with four-fold increased odds for suicide plans in young people. Self-harm is also aetiologically associated with childhood maltreatment. Sexual violence is associated with a higher risk of self-harm and attempted suicide in both boys and girls. It is estimated that in the absence of sexual abuse, the female suicide attempt over lifetime would fall by 28% relative to 7% in men. Dutch Psychiatrist Bessel Van Der Kolk estimates that the costs of child abuse exceed those of cancer or heart disease and that eradicating child abuse would reduce the overall rate of depression by more than half, alcoholism by two-thirds, and suicide and IV drug use, and domestic violence by three-quarters.’ Sexual assault is associated with an increased lifetime rate of attempted suicide. A history of sexual trauma in females before the age of 16 is a particularly strong correlate of attempted suicide. Whilst children exposed to trauma by age 6 are between 50 and 100% more likely to develop psychiatric conditions than non-exposed children.

THE IMPORTANCE OF MARRIAGE AND FAMILY STRUCTURE FOR CHILD OUTCOMES

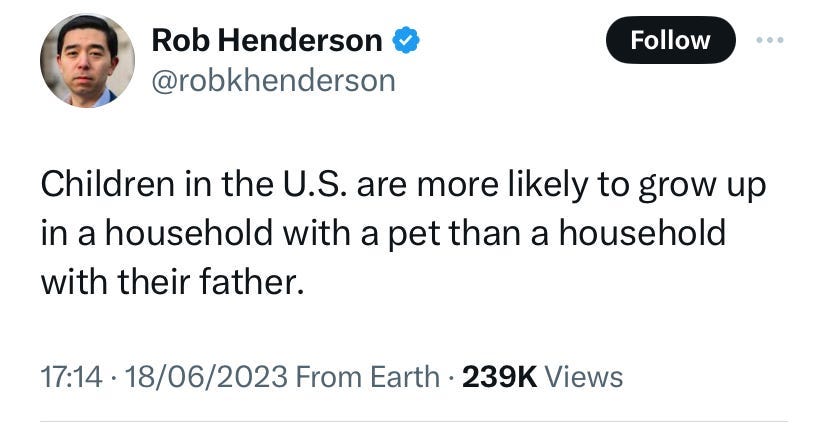

The importance of marriage and of family structure for child/adolescent mental health is that children who are raised by their own married biological parents are less likely, on average, to be exposed to the forms of child maltreatment which are associated with a higher risk of mental ill-health, because biological parents are less likely to harm their children than unrelated adults are. People are more likely to harm, neglect, or kill step-children than their own biological children (Cinderella effect.) Children living with one genetic parent and one step-parent are approximately 40 times more likely to be abused than children living with both genetic parents. This greater rate occurs even when controlling for poverty and socioeconomic status. Young children who live in households with one or more unrelated adults are nearly 50 times as likely to die from an inflicted injury, usually being shaken or struck, as children living with two biological parents. Across diverse cultures, a man who lives in the house with another man’s children is about 60 times more likely than the biological father to kill those children. Being part of a single-parent household increases the odds of experiencing child sexual exploitation threefold. As Joseph Henrich has put it:- ‘By increasing the relatedness within households, normative monogamy reduces intra-household conflict, leading to lower rates of child neglect, abuse, accidental death and homicide.’

Marriage reduces the odds that children will be exposed to the forms of family instability that are associated with higher exposure to adverse childhood experiences because married parents are more likely to stay together than cohabiting ones. Some studies estimate that children born to cohabiting couples are about 90% more likely to see their parents break up by the time they turn 12. Whilst Bobby Duffy, in his book ‘The Generation Divide: Why We Can't Agree and Why We Should’ writes that ‘study after study has shown that children in households with both their married parents, on average, do better than the alternatives….in the end, stability matters, and it tends to be greater in married households, despite claims that long-term cohabitation is equivalent. Children in France, for example, are 66% more likely to see their parents break up if they are cohabiting rather than married.’

CARE LEAVERS OUTCOMES

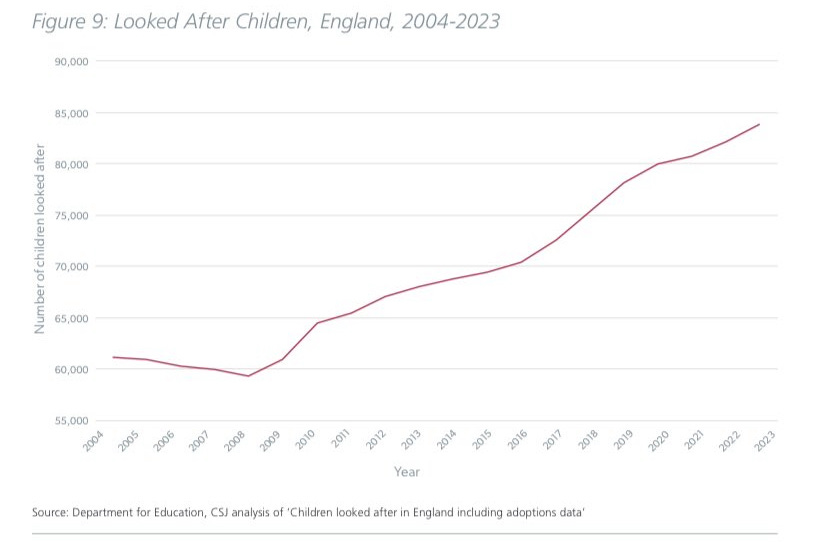

The statistics for children raised in care - i.e not by their biological parents - vividly illustrate the link between family structure and mental health outcomes. Children who grow up in any type of care setting are 70% more likely to die prematurely than those who do not, with most of these occurring as a result of some kind of self-harm, or because of accidents or because of mental and behavioural causes. One study found that 45% of looked after children in England have a diagnosable mental health disorder compared to one in ten of the general population. Another study found that almost three quarters (72%) of those in residential care, were clinically diagnosed with a mental disorder. Other studies have found that longer placements and multiple placements were associated with more extensive adult emotional and behavioural difficulties. Compared to their siblings never placed in out-of-home care, children placed in foster homes are three-times more likely to have depression/anxiety, and are also more likely to be prescribed Psychiatric medication. In America, in at least one state, it was discovered foster children were 19 times more likely to be prescribed 5 or more psychiatric medications than non-foster children and that 66% of foster children aged 13 to 17 are on at least one psychiatric medication. People with experience of the care system have been found to be 4 to 5 times more likely to attempt suicide in adulthood than their peers and another study of deaths by suicide in those under the age of 20 found that nearly 1 in 10 had experience of the care system.

FAMILY BREAKDOWN HAS BECOME NORMALISED WITH BALEFUL CONSEQUENCES FOR THE MENTAL HEALTH OF CHILDREN AND ADOLESCENTS

The outcomes for children raised in care, i.e for children who are not raised by their own biological parents, are sobering and reveal a fundamental truth: the mental health of any child or adolescent cannot be understood without an understanding of the family-context in which the child/young person is situated, the two things cannot be fully separated or analysed in isolation. This is true for all children/adolescents, not just those raised in care, albeit the outcomes are more stark for those children who are raised in care. Research indicates that the most important factor in the mental health of adolescents is the quality of the relationship with their parents/caregivers and that children who simultaneously had secure attachment relationships with both mothers and fathers were likely to experience fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression.

As a culture we have moved seamlessly from a stance of - ‘we shouldn’t stigmatise people who fall outside of traditional family structures’ - which is reasonable - to the complete denial of the reality that different forms of family structure are associated with different child outcomes on average - which is not reasonable or helpful. As a child of divorced parents and someone who has been divorced as an adult, I intimately understand that heterodox family arrangements are sometimes an unavoidable fact of life, but I also understand from two decades of clinical experience that this does not mean that all forms of family structure are therefore created equally. It is necessary to reiterate that children raised by their married biological parents have better life outcomes in general, and better mental health outcomes in particular, not because one wishes to preach a moralising sermon drawn from religious dogma but because one wishes to point to an empirical fact established by social science.

{source}

The CSJ reports that the UK is an outlier among its counterparts for family fragility, with 23% of UK families headed by a single parent, compared with an EU average of 13%, and that the proportion of cohabiting families has doubled in the last two and a half decades (statistics which are closely matched in an American context in which 30% of children live with only one parent or no parents and close to half of all babies are born to unmarried mothers compared to only 5% in 1960..) The IFS has also reported that in 1971 in England and Wales, 8% of births were recorded as being outside of marriage, but by 1991 this had more than tripled to 30%, and that it stood at 48% in 2019. The IFS has also reported that from 1986 to 2018, the fraction of local authorities with over 1 in 10 of births to lone mothers increased from 39.9% to 79.3%. Additionally, the IFS has reported that amongst children born in 1958, 9% had experienced parental separation by age 16, for children born in 1970 this had increased to 21%, and for children born in 2001–02, it increased again to 43%. The Guardian reported in 2018 that ‘Between 2010 and 2016, the number of children assessed by social workers as as being in need rose by 5%, the number of children subject to a child protection plan increased by 29%, and numbers in care were up 10%.’

This set of statistics, and the lack of societal concern for their direction of travel, are indicative of the fact that family breakdown has become normalised and that well-meaning attempts at reducing the stigma of ‘broken homes’ has lulled us into the false sense of security that all forms of family structure are created equally, with potentially baleful consequences for child outcomes in general.

As regards mental health outcomes specifically, a lot of attention has been focused on self-harm among teenage girls. Some people believe that deliberate self-harm (DSH) is a transdiagnostic thing but in clinical practice *recurrent* DSH is overwhelmingly a borderline personality disorder (BPD) thing and BPD unfortunately has strong associations with child maltreatment. Child maltreatment can potentially happen in any type of social/family context but it is more likely to happen in certain types of social/family contexts than others. To be clear, not everyone who self-harms has BPD, and not everyone who has BPD has been maltreated or abused either, but what I am saying is that in clinical practice *recurrent* DSH is overwhelmingly a BPD phenomenon and BPD unfortunately does have strong associations with childhood maltreatment, including abuse. Childhood maltreatment is unfortunately more common in certain types of family contexts than others, such as families with higher rates of instability and dysfunction. If this a problem we wish to face then its essential that we properly grasp the risk factors commonly associated with its aetiology rather than chasing red herrings such as social media use.

One of the problems with any public debate about mental health is the term itself. ‘Mental health’ is routinely conflated with ‘mental wellbeing’ but they are two different things. Can social media use effect your wellbeing? Yes, anything can, potentially, dependent on type of use and wider context. But thats not the same as saying it causes mental illness. There is no such thing as Instagram-induced mental illness but there is such a thing as drug-induced mental illness. When we talk about mental wellbeing we’re talking about the normal range of emotions. Mental illness is different. The core symptoms of Paranoid Schizophrenia, for instance, are not part of the normal range of emotions, nor the declines in functioning associated with them either.

Perhaps we need to stop using the term ‘mental health’ altogether because it has been a source of so much confusion. Perhaps we should start talking about Psychiatric illness instead for greater clarity. What causes Paychiatric illness? Usually a combination of endogenous/innate factors and psycho-social stressors/exogenous factors. What exogenous factors are associated with Psychiatric illness? Depends on the type of Psychiatric illness and also depends on the propensity of the person to develop certain types of Psychiatric illness too. As regards Psychiatric illness among teenage girls, recurrent deliberate self-harm is not uncommon in this demographic group. As regards *recurrent* deliberate self-harm its very difficult to say what causes these types of behaviours but unfortunately a history of trauma/abuse is not unusual, likewise, a history of family instability/dysfunction.

In teen girls with these pre-existing problems its certainly conceivable that they could use social media in such a way that isnt helpful, absolutely. But the idea that social media causes their problems out of whole cloth is a nonsense Im afraid and needs to be called out as such because it has caused us to lose all sense of perspective as regards what the common risk factors for these types of disorders actually are. Psychiatric illness arises due to a combination of innate factors and psycho-social/environmental stressors. Some people are more vulnerable than others. Among young people the factors that make them more vulnerable, as well as hereditary factors, are family context (amongst others.) We don’t use terms like ‘orphan’ or ‘broken homes’ anymore but these are the types of kids who are most vulnerable, kids from these types of backgrounds. Its not their phones thats made them vulnerable, it’s the instability and dysfunction of the family context that they’ve been raised in and thats where our focus should be.

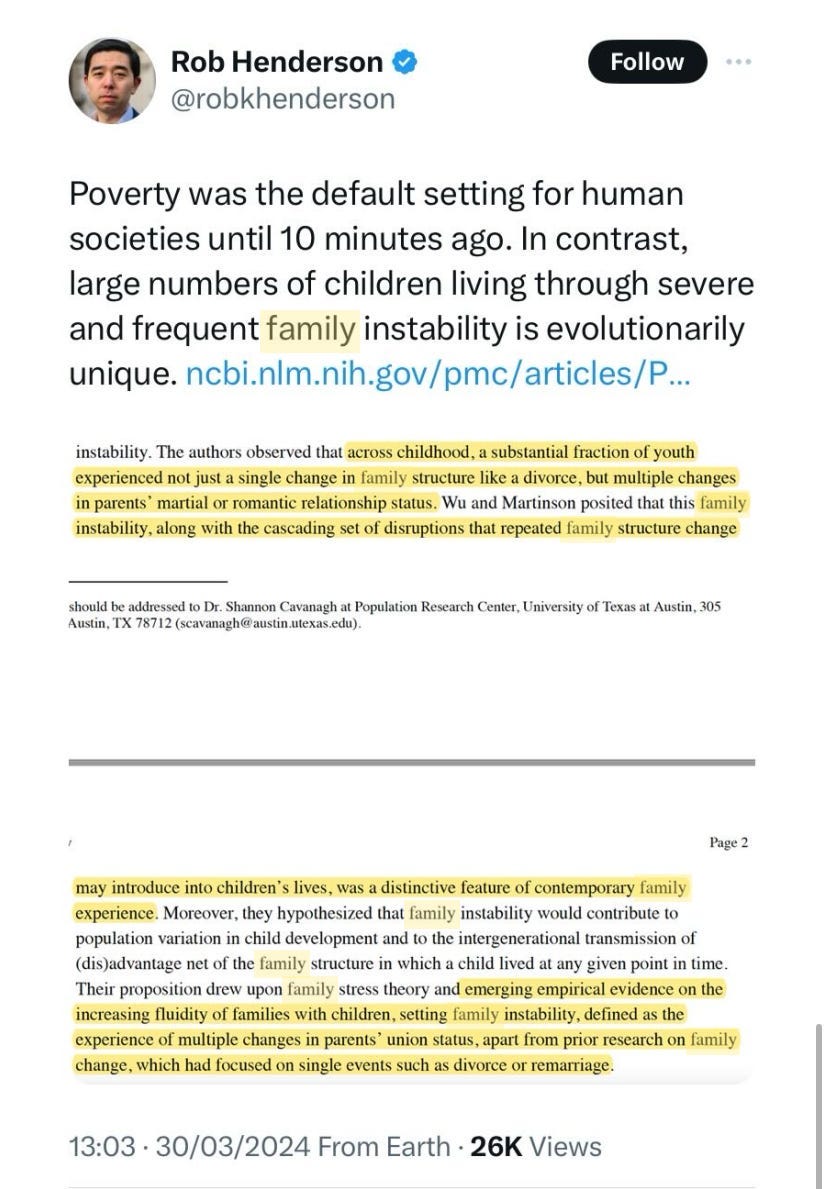

{source}

CONCLUSION

The importance of marriage and of family structure for child/adolescent mental health, among other reasons, is that children raised by their own married biological parents are less likely, on average, to be exposed to the forms of child maltreatment which are associated with a higher risk of mental ill-health, because biological parents are less likely to harm their children than unrelated adults are and because married parents are more likely to stay together than cohabitating parents are. Being raised by your married biological parents is no guarantee that you will not be exposed to maltreatment and other forms of adverse childhood experiences, but the evidence suggests that it reduces the risk, and is therefore a vital safeguard to protect children from harm. And, as a corollary, because so much of child/adolescent mental ill-health is linked to adverse childhood experiences, being raised by your married biological parents is hugely important when we consider the topic of child/adolescent mental health too. Children raised in care have the worst mental health outcomes and what those children have in common is family-context, not screen-time. What we see in more extreme form with respect to children raised in care is seen to a lesser extent in children/adolescents exposed to varying degrees of family conflict, dysfunction and breakdown.

As someone whose parents separated when he was 12 and whose first marriage failed as an adult, Im intimately aware that heterodox family arrangements are sometimes an unavoidable fact of life. There is no moral judgement here. For me, this is an empirical matter, certain forms of family structure are associated with better life outcomes in general for children and this is also reflected in mental health contexts. I don’t think its helpful to stigmatise anyone who falls outside of traditional family structures and arrangements but nor do I think its helpful to deny the reality that certain forms of family structure are associated with better outcomes for children either. Alongside substance misuse, a background of family dysfunction/instability in general (not necessarily outright abuse) is the most common correlate of mental health difficulties in young people that I have encountered. What matters most for young people is what happens in their offline lives, at school, and, especially, at home. That hasn't changed.

{source}

Hi Pete,

Is there evidence that the rise in divorce and family breakdown has increased the overall number of ACE that kids are exposed to hence driving worse mental health?

Playing devil's advocate, I presume progressives would say that easy, rapid divorce, etc reduces overall ACE by not trapping kids in homes with unhappy or abusive parents.

Is there any way to try to answer that question at the overall quantitative level of society?

You are undoubtedly correct. The problems go deeper than just phones or social media and American family structure leaves many vulnerable. In my view, phones/social media are one of a number of accelerants or evangels, making problems with social structure get worse and spread.

In the 1940s/50s many were worried about the atomizing and family splitting impact of TVs in the home. I think it's useful to see the problems of American family structure and the proliferation of screens as related.