JUMPERS FOR GOALPOSTS: THE DECLINE OF THE STREET FOOTBALLER

What we talk about when we talk about Diego Maradona

‘It might reasonably be maintained that the true object of all human life is play’ (GK Chesterton)

‘Play is the highest form of research’ (Albert Einstein)

‘Play is often talked about as if it were a relief from serious learning. But for children play IS serious learning’ (Fred Rogers)

INTRODUCTION

In my last Substack post I wrote about the changes that have taken place in professional football over the last thirty years, with a particular emphasis on English football. In this post I want to continue with the theme of changes in the footballing world over the last thirty years but focus this time on the decline in (what I refer to in the piece as) the street-footballer-to-creative-playmaker-pipeline, with a particular emphasis on the best footballer of my childhood.

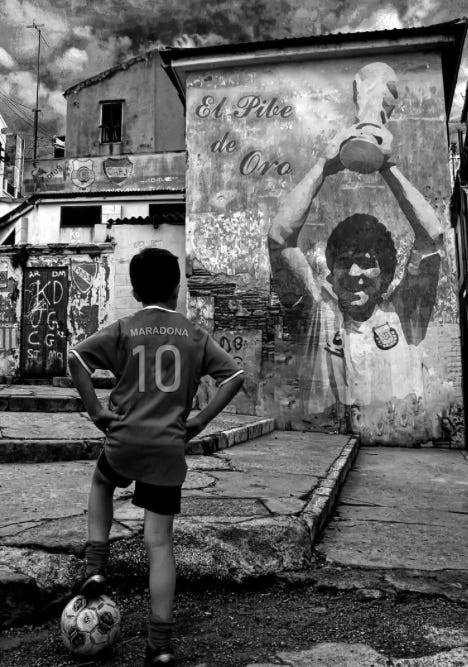

THE GREATEST STREET FOOTBALLER OF THEM ALL

When I first fell in love with football, aged seven, the best player in the world was Diego Maradona. Only the year before, he had reached the pinnacle of his career, indeed, the pinnacle of any footballer’s career, by winning the World Cup with his national side Argentina. Maradona’s star shone more brightly on the world stage at that tournament (when the World Cup was still basically the only opportunity for the best players in the world to face each other in meaningful competition) than had ever been seen before (or since) on a football-pitch. This achievement raised Maradona to a level of superstardom that only a handful of footballers have ever reached and, even to this day, he is idolised in the places that he made his footballing mark, such as the Argentine capital of Buenos Aires and the Southern Italian city of Naples, whose team, Napoli, he dragged, virtually single-handedly, from the bottom of Serie A to the top-table of European football in the space of only a few years. This unlikely sporting superhero, who stood at only five foot four inches tall, and had emerged from humble origins, as a slum kid from a Buenos Aires shanty town, represented what footballing genius looked like to someone my age and what every young boy aspired towards when they had a football at their feet. For many football fans, he was the reason why they fell in love with football in the first place.

Simply put, Maradona was more than just a footballer, he was the personification of an archetype and that archetype is that of the street footballer. At its most basic, fundamental level, football is a form of play, something to be enjoyed for its own sake, an activity that is intrinsically motivated, not a means to an end, but an end in itself. In the era in which Maradona played, before the game had reached its current levels of professionalisation, many of the world’s greatest players had developed their skills, and honed their styles of play, not necessarily in football academies — where young boys are now moulded into shape by the market for young boys that treats them as commodities via an industrialised process of youth development which is geared towards the maximisation of profit — but literally on the street, guided by nothing but their enjoyment of the game for its own sake. Maradona, with his free-spirited, individualistic style of playing football, was a paradigmatic example of this type of development.

Diego Maradona was born in 1960, in a Buenos Aires shanty town, to a Mestizo father, employed in a bonemeal crushing factory, and to a mother of Italian immigrant stock, employed as a domestic. Maradona was raised in a shack without running water or electricity but was given a leather football, when aged three, by his cousin. As his biographer, Jimmy Burns, put it: ‘during the day he’d kick it about in the waste ground around his home in Villa Fiorito, a shanty suburb of Buenos Aires. There, as the ball bounced awkwardly over the dust and stones, the young Diego Maradona learned his first tricks, gradually turning his anarchic toy into a source of skill and inspiration.’ As Diego himself puts it in his autobiography:- ‘Sometimes now when I hear someone going on about how in such and such a stadium there's no light, I think: I played in the dark, you son of a bitch! I don't know if we were street children: I guess we were 'potrero' (waste ground) children more than anything. If our parents were looking for us, they knew where to find us. We would always be there in the potrero, running after the ball.’

Whereas a footballing diamond like Lionel Messi was polished at the elite FC Barcelona youth academy, La Masia, and was raised in a comfortable lower-middle-class home, Maradona came from a slum and learned to play football literally on the streets. Comparing Lionel Messi to Diego Maradona therefore is tantamount to comparing a lab-grown diamond to one which arose naturally from the earth’s surface. Lionel Messi, a polished diamond, may well be the greatest footballer who has ever lived, but Diego Maradona, the rough/uncut diamond, remains the greatest street footballer who has ever lived. In ‘The Ball is Round: a Global History of Football’ by sociologist David Goldblatt, he contrasts the two greatest Brazilian footballers of the 1960’s i.e Garrincha and Pele, in illuminating fashion:- ‘Pelé planned for the future. Garrincha lived for the moment. Pelé trained. Garrincha slept. In their later years both players acquired another nickname – an essential suffix. Pelé was O Rei – ‘the King’, honoured, but ultimately distant, of another world. Garrincha was O alegria de povo – ‘the joy of the people’, of this imperfect world, disabled, drunk, fragile and ultimately broken. The King was and is revered but Garrincha was loved.’ Lionel Messi, like Pele, is also distant, of another world, whereas Diego Maradona was more like Garrincha, of this world, imperfect, and loved by the masses in much the same way.

MODERN-DAY FOOTBALL YOUTH ACADEMIES

Diego Maradona belonged to one of the last generations of free-range footballers, before the enclosure of childhood fenced off unstructured, independent play, and before aspiring young footballers were placed into the battery cages of the modern-day youth-academy. As regards modern-day football youth academies, football writer David Conn has written that:- ‘The Premier League and Football League clubs wrestled control of so many young boys sporting childhoods from schools and grassroots clubs with Howard Wilkinson’s Football Association “Charter for Quality” 20 years ago….Now Premier League clubs are globally focused, aggressively commercial corporations mostly owned by absentee overseas investors, Wilkinson says they are failing in a “moral responsibility” to give their academy players opportunities.’

Sportswriter Ryan Baldi, in his book ‘The Dream Factory,’ spells out the realities of the system that has been created: ‘There is a very uneasy sense of youth development having been industrialised…. it has gradually been recognised..that children who enter academies from eight years of age unwittingly sacrifice a chunk of their childhood toward the football dream. With such high dropout rates, there is a risk that, down the line, the many who don’t graduate to a career in the game will feel they missed valuable developmental experiences for no reward…The sheer number of players within the academy system… means the vast majority are somewhat cruelly considered mere ‘bodies’, whose presence is essential in aiding the development of the gifted few.’

The wisdom of taking very young boys out of local and school football and placing them in a youth-academy setting is questionable for a number of reasons, not least because the overwhelming majority of them will never secure a future career as professional footballers. The BBC has reported that: ‘Of the 1.5 million players who are playing organised youth football in England at any one time, around 180 - or 0.012% - will make it as a Premier League professional. More than three-quarters of academy players are dropped between the ages of 13 and 16.’ Michael Calvin, in ‘No Hunger in Paradise,’ has written that: ‘Less than one half of one percent of boys who enter the academy structure at the age of 9 will make a first-team appearance….Almost 98% of boys given a scholarship at 16 are no longer in the top five tiers of the domestic game at the age of 18. A recent study revealed only 8 out of 400 players given a professional Premier League contract at 18 remained at the highest level by the time of their twenty-second birthday.’

The hot-housing of children at such young ages — Williams and Wigmore report that in 2013 the Belgium club FC Racing Boxberg signed a 20 month old and that in 2019 Manchester City launched a ‘junior academy elite squad’ for the under-fives — also means that the selection of youngsters becomes more vulnerable to the ‘relative age effect’ too, which skews selection in favour of children who are older and more developmentally mature and which places children who are late-developers at a greater disadvantage. Williams and Wigmore explain the relative age effect thusly: ‘in sport, the selection year does not always align with the school year…..yet, whatever month the selection year begins, the relative age effect persists; those who are born earlier in the selection year have a far greater chance of being selected for youth teams or academies. Late-born children are further disadvantaged if they are physically immature for their age.’ Williams and Wigmore go on to explain that ‘45% of players in men’s Premier League academies have historically been born in the September–November window, compared with only 10% from June–August….At the European U17 Championships in 2019, 47% of all players were born in the first quarter of the selection year and only 6% in the last quarter….Steven Gerrard and Frank Lampard, two of the best England footballers of their generation, were both rejected by the Football Association’s national academy at Lilleshall; Gerrard was born on 30 May, and Lampard on 20 June, both late in the selection year.’

Whilst there has been further reform of the English football youth academy system since 1997, notably in 2012 with the ‘Elite Player Performance Plan,’ problems remain. Ryan Baldi explains:- ‘For all the good that EPPP has ushered in…. there has unquestionably been a cost, human and financial….When Manchester United and others first founded affiliate youth clubs, they were designed to be refineries for the best local talent and a means of reaffirming a cherished connection to their place and their people. In that sense, the modern academy machine is in danger of losing touch with its humble beginnings.’ Williams and Wigmore also report that ‘In one recent study, over 25 per cent of English football academy players reported mild to moderate depressive symptoms; 15 per cent exhibited symptoms suggesting the possibility of major depression.’ This gives us an insight into some of the stresses that young boys in football academies are under, stresses which can sometimes contribute to the loss of life.

Long story short, a once-in-a-lifetime preternatural genius like Lionel Messi aside, it's far from obvious that the football factory setting of a modern-day youth academy can reliably serve as a veritable philosopher’s stone that can transmute the base metal of raw human potential into the gold of a footballing genius like Diego Maradona. The skill-set of a great street-footballer (such as the aforementioned Maradona,) has, by definition, arisen organically, from years of playing football on the streets, where he has learned, in the absence of adult supervision, to be physically tough and aggressive but also to develop mastery over the football on a variety of different surfaces, whilst also having the licence to experiment with tricks, step-overs, feints and shots from long distances/acute angles (i.e to be creative,) via endless one-on-one duels in tight spaces and on uneven surfaces. To quote Wigmore and Williams:- ‘Clairefontaine {the famous French national football youth academy} gives players the best possible chance to make good on their full potential. Yet, while the academy polishes and refines the gems, it does not make them. That work is done… in the ballon sur bitume {French term for street football} played in the streets, cages and parks around them.’

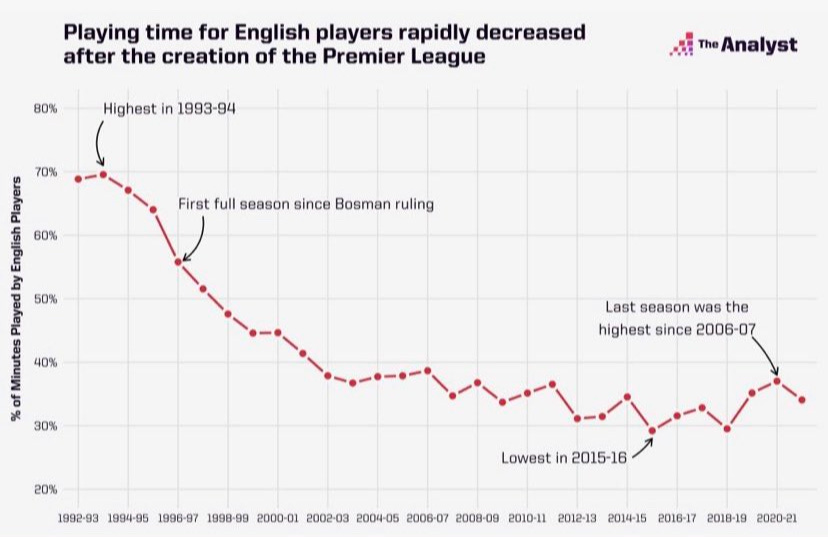

The irony of the modern-day English youth academy system is that English Premier League (EPL) clubs now spend millions every year on youth academies, with the aim of developing homegrown players, only to end up with their rosters full of foreign players who have developed their skills in street football settings. In regards to the big five European leagues (England, France, Spain, Italy, Germany,) the English top-flight now ranks the lowest in terms of giving minutes to home nation players (34.1%.) The proportion of English players starting matches in the Premier League fell from 71% in 1992-93, down to just 30% by 2018, and between 2013-2022 only 37% of all EPL signings were of English players. Plus, no ‘big six’ club in England (i.e Liverpool, Manchester United, Manchester City, Arsenal, Chelsea and Spurs) have more than 40% homegrown players in their squads.

As stated previously, the irony of our youth-development system, which encourages early specialisation in the supervised/structured environment of the youth academy, is that EPL clubs have become increasingly reliant on other countries to produce players that are good enough to play in our top-flight and those players have disproportionately come from unsupervised/unstructured street footballing cultures that are the antithesis of our own model. France currently provides more players to the top five European leagues than England, Germany, Spain or Italy and the greater Paris region has produced more players that have played in the last five World Cups than any other metropolitan area in the world (including eight of the French squad that won the 2018 World Cup.) Unsurprisingly, the top foreign nationality for EPL players is French. Why have so many great players (such as Kylian Mbappe) come from the Banlieues of the Ile-De-France in particular? The answer, in large part, is due to its street footballing culture, dubbed ‘Ballon Sur Bitome,’ (which literally translates to ‘concrete football’,) a fact that is acknowledged even by French youth academies themselves.

Brazil exports more footballers to the rest of the world than any other nation, France are second, including a sizeable number to the EPL, and, just like France, a sizeable number of those players have come from a street footballing background. Futsal (an indoor form of football) and beach-football are highly popular in Brazil and are both small-sided games that resemble street football, and then there is ‘Pelada,’ a term that translates to ‘nude,’ which is a particularly Brazilian style of street football. Uehara et al explain what ‘Pelada’ is in these terms:- ‘Pelada is usually played outdoors on irregular surfaces e.g., streets, beaches, yards… Pelada is not coached or planned or supervised by adults who interfere and start to prescribe ways to perform skill. In contrast, it represents unstructured or informal play….many talented Brazilian football players aged 16 to 17 years, tend to have received little, if any, structured coaching in programs, in contrast to a multitude of unstructured football experiences played on the streets…. The range of informal situations in which Brazilian players develop their talent appears to provide perceptual-motor expertise which is adaptable, innovative and effective if the global reputation of Brazilian footballers can be used as a gauge.’ Williams and Wigmore state that ‘the best Brazilian players tend to spend as much time engaging in football activities in their formative years as those from other countries, but a far higher portion is through informal play.’ Whilst Button et al emphasise that ‘this informal way of playing football in Brazil…on irregular surfaces, played with bare feet, and on small and deteriorating playing spaces….can actually be beneficial for the development of a high level of perceptual-motor skills.’

Even in England, a disproportionate number of our top-class footballers are still produced in the dwindling number of locations where a culture of street football still prevails. South London, with its vibrant cage football scene, being a prime example. As of 2016, 14% of English footballers in the Premier League were from a ten mile square of south London, with Croydon alone (home to just 0.6% of the population) producing 5% of all active English Premier League players. The decline of street football in England is important because, as Williams and Wigmore put it, ‘the amount of informal play…that athletes engage in during childhood correlates strikingly with how successful they are in sport later in life. A healthy amount of informal play cultivates creativity, freethinking and technical expertise; a diet of rigid and hyper-serious coaching alone can be detrimental.’ In other words, the decline of street football is likely to result in less footballing creativity and flair.

It is important to stress that the decline of street football — outside of its last bastions of the South London cage football scene, the Ballon Sur Bitome of the banlieues in Ile-De-France and the Pelada of the Brazilian favelas — is only partially attributable to the rise of the modern-day football youth academy system. The decline of street football also reflects the trajectory of child-socialisation in general. According to some estimates, ‘child-based exploratory play has declined. In the United Kingdom, research has found that children today play outside on average slightly more than 4 hours per week, compared to 8.2 hours for their parents' generation.’ According to an article published in 2016 by The Guardian, three-quarters of UK children spend less time outdoors than prison inmates. A report by a British think-tank named Onward noted that:- ‘‘The average age at which children are being allowed out to play on their own has risen from 9 to 11 years old within the last generation, with implications for children’s social development.’ The enclosure of childhood has multiple causes and multiple implications, and is something I wish to explore in more depth in a future Substack post, but needless to say that the decline of street football is reflective of wider societal trends.

Wayne Rooney, who you could argue was the last great English street-footballer of the classic type (i.e as pugnacious as he was skilful,) has spoken, in the 2022 Amazon documentary about his life, about the differences between his childhood (he was born in 1985) and that of his sons (he has four sons, the eldest of which was born in 2009.) Rooney notes, in particular, that when he was a pre-teen, he would usually be found outside in the street playing football, unlike his sons, who would be more likely to be found inside the house playing computer games. In a previous Wayne Rooney documentary, made in 2015 by the BBC, you get a glimpse into that street footballer childhood when he recalls how he celebrated scoring his first goal for Everton, when aged 16, that is, by returning to his local area of Croxteth in Liverpool to play football on the streets with his friends, something that would be harder to imagine the current crop of elite young footballers doing, given the extent to which they are now protected.

The likes of Wayne Rooney and Diego Maradona belong to a bygone era —famously satirised by the phrase ‘jumpers for goalposts’—one in which young footballers were given more freedom to develop in an organic fashion, before footballing youth-development became cemented in its modern-form. Street footballers, like Rooney and Maradona, are akin to the last generation of men to win Wimbledon with a wooden tennis racket. The individualistic style of the classic street footballer is just too idiosyncratic to be mass-produced on the production-line of a modern-day youth academy. Additionally, the central and advanced creative playmaker role, which Maradona, in particular, excelled in, has now been rendered, more or less, obsolete by modern systems of play, which place greater emphasis on systems of collective organisation than on Maradona-style individual brilliance. Maradona’s style of football is like the hand-crafted goods produced by the skilled craftsmen of the middle ages who were largely swept away by the onset of mechanised production during the industrial revolution. They belong to a world that no longer exists, a world of individual craftsmanship before the arrival of the mass production of standardised goods.

THE NUMBER TEN POSITION

Creative playmakers have come in all shapes and sizes over the years, they have played in central-defence (libero,) central-midfield (regista) or out wide, as in the traditional British model. For whatever reason, in traditional British football, wide positions have been the places where skill and trickery have been sequestered, whereas in Brazilian football, in contrast, skill and trickery has been seen as belonging everywhere on the pitch. In that sense, every Brazilian player is a winger, irrespective of where he actually plays. Whereas, in traditional British football, the idea that skill/trickery can break out from its confines on the wing has traditionally been met with greater levels of suspicion. The distillation of this tendency can be seen in the British distrust of ‘showboating’ which is viewed as inherently attention-seeking, showy, and un-British. However, the predominant model of creative playmaker, in most footballing cultures, has tended towards the advanced central playmaker position, simply because he was better positioned to influence play, given that he operated in an advanced/central position further up the pitch, where he could receive more of the ball.

In footballing parlance, the advanced central playmaker was usually referred to as a ‘number ten.’ In literal terms this just meant that he wore the number ten on the back of his shirt, but in football terms this denoted that he was the creative playmaker of the team, the closest that football has come to an equivalent of a quarterback role in American football. The number ten wasn't just another player, he was the star, the fulcrum around which the rest of the team was organised. In Argentinian football this role was given the term ‘enganche,’ which translates to ‘hook,’ because such a player acted as the hook between the midfield and attack. In Italian football the number ten role was given the name ‘trequartista,’ which literally translates as ‘three-quarters,’ because the number ten operated in the spaces between midfield and attack approximately three-quarters of the way up the field. Too far advanced to be classed as a midfielder, too deep-lying to be categorised as a forward, the number ten was a category unto himself. The role invariably attracted mavericks (Eric Cantona immediately springs to mind here,) and footballing mavericks have often been street-footballers in origin.

THE WEBERIAN CONCEPT OF DISENCHANTMENT APPLIED TO FOOTBALL

Diego Maradona’s rags-to-riches life-story illustrates the street-footballer-to-number-ten-pipeline most vividly. The number ten is essentially a romantic figure, a Byronic hero in football boots, and the flawed genius of Maradona fits the bill perfectly. Footballers of his type - not just Maradona but also Pele, Puskas, Cruyff, Rivelino, Zico, Rivaldo, Ronaldinho, Kaka, Hagi, Platini, Zidane, Cantona, Baggio, Totti, Zola, Del Piero, Bergkamp, Dalglish, Hoddle, Beardsley, Rooney, Le Tissier, Riquelme, Michael Laudrup, Lionel Messi and Neymar - represent a big part of why so many of us fell in love with football in the first place, so the idea that this footballing species is becoming extinct represents a significant sense of loss. As I wrote in my previous Substack post, the commercialisation of football, which has accelerated over the last thirty years, has radically altered it, both for good and bad. Thomas Sowell wrote that ‘‘there are no solutions, only trade-offs” and football has traded greater professionalisation (something that has accompanied its greater commercialisation,) for a loss of footballing magic and wizardry.

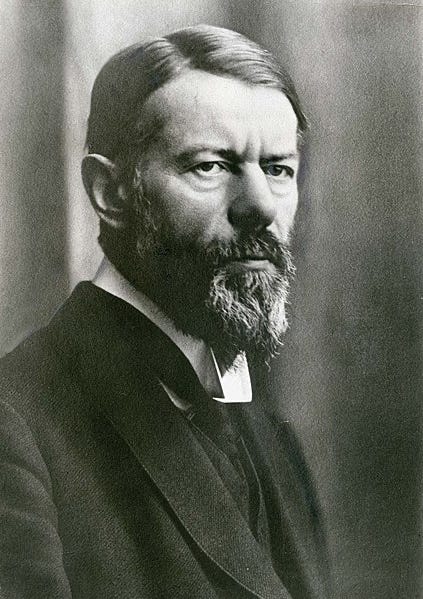

The 19th century-born German sociologist Max Weber referred to the process whereby Westernised/industrialised societies gradually lost their faith in religion as a process of disenchantment in which demystification led to a loss of meaning. As one writer on Weber has put it:- ‘The march of science and technology had led to what Weber famously called “the disenchantment of the world”: through our discovery and use of the laws of nature, we have drained it of its mystery and majesty.’ This is analogous to the changes that have taken place in football over the last thirty years. Essentially, there is so much money flowing through the game now, and the risk of failure, in what is now a multi-billion-dollar industry, has become so precipitous as a consequence, that nothing can be left to chance and this leaves little room for the inherent unpredictability of a number ten and, by extension, little room for street-footballers too. In their place we have Moneyball-inspired data-analysts armed with mathematical equations in the search for greater efficiency instead. In the process, the game has lost some of its lustre. A sense of awe is good for the soul and the sight of Maradona slaloming his way through an entire defence on his own, or Hagi shooting at goal from ridiculous distances and impossible angles, or Zidane pirouetting on the ball to bamboozle a defender, meets the deeply-felt human need for wonder in a way that no amount of statistical analysis or mathematical rationality can match.

The disenchantment of football has rendered it more predictable and less exciting. We know, with a fair amount of certitude, that Manchester City are highly likely to win the English Premier League most years, that Bayern Munich are highly likely to win the Bundesliga each year, that one of Real Madrid, Barcelona or Atletico Madrid are highly likely to win La Liga each year and that one of Juventus, Inter Milan or AC Milan are highly likely to win Serie A most years. We accept the dominance of Real Madrid and Barcelona in Spain as normal even though it wasn't that long ago that it was possible for the likes of Valencia and Deportiva La Coruna to become La Liga winners and even though it was possible for Aberdeen to beat Real Madrid and for Dundee United to beat Barcelona in Europe as recently as the 1980’s. We accept the dominance of Bayern Munich in Germany as normal, even though it wasn't that long ago that they were beaten by Hearts and Norwich in Europe, and even though it wasn't that long ago that the likes of Werder Bremen and Wolfsburg and Stuttgart were able to win the Bundesliga. We accept the dominance of the big three of Juventus, Inter Milan and AC Milan in Italy as normal, even though it wasn't that long ago when Hellas Verona and Sampdoria could win Serie A, never mind Roma and Lazio. We accept the fact that the English Premier League trophy has moved out of Manchester and London on only three occasions in the last 31 years despite the fact that, prior to this, in the post-war period, the English title was won by clubs from Birmingham, Derby, Nottingham, Wolverhampton, Portsmouth, Burnley, Ipswich, Liverpool, Leeds, as well as Manchester and London. We also know that clubs from those four leagues are highly likely to win all the major European competitions each and every year. We accept the domination of European football by a small number of clubs, from a limited number of countries, as normal, even though, as recently as the 1980’s and the 1990’s, it wasn't unusual for clubs from the periphery of Europe, i.e Eastern Europe and Scandinavia, plus clubs from the smaller countries of Scotland, the Low Countries and Portugal, to win European competitions.

THE COMMERCIALISATION OF FOOTBALL

The commercialisation of football has made the game more predictable, via the huge economic inequalities it has engendered between clubs, and we can see this at a national level, at a continental level, but also at a granular, match-by-match level. In the prelapsarian world of the number ten, whilst defensive play was usually structured/organised, attacking play, on the other hand, was typically more unregulated/instinctive, and this gave the number ten more licence to improvise. However, in the modern game, things like shots from distance and also dribbling past players with skill and trickery (i.e the types of attacking play that we would associate with a classic number ten,) whilst exciting for the spectator to watch, involve greater risk of handing possession of the football over to the opposition, and have thus become less prevalent as the demand for constant results drives riskier forms of play out of the game. The commercialisation of football has also placed huge pressures on managers to get instant results and, as a consequence, are now sacked at a much faster rate than was the case until the arrival of the modern era. The average tenure of a professional English manager dropped from over seven years, post-World War Two, down to three years at the Premier League’s inception (1992-93) and all the way down to 423 days by 2020.

These pressures have driven managers to seek ever-greater levels of control over what happens on the pitch, resulting in attacking play becoming as organised/systematised as defensive play, rendering it a lot more structured/ordered in the process. Out with the long-distance shots and the dribbling and in with the juego de poisicion and the gegenpressing. As Jurgen Klopp says in ‘The Mixer’ by Michael Cox:- ‘Think about the passes you have to make to get a number 10 in a position where he can play the genius pass. Counter-pressing lets you win back the ball nearer to the goal, and it’s only one pass away from a really good opportunity. No playmaker in the world can be as good as a good counter-pressing situation.’ The ever-increasing levels of commercialisation in football drives ever-increasing levels of professionalisation and the ever-increasing levels of professionalisation drives ever-increasing levels of organisation and systematisation in how it is played on the pitch, both in defence and in attack.

The classic number ten, an individualist by nature, is ill-suited to this type of collective discipline and does not even have a role to play in the now ubiquitous 4-3-3 formation, that is employed by managers to ensure a good shape when a team presses high up the pitch. Unless, that is, he converts himself into a work-horse, to fit into a midfield-three, or into a goal-machine, to slot into a forward-three, either as an ‘inverted-winger’ - less a traditional winger than a ‘wide forward’ - or as a so-called ‘false-nine,’ i.e if he becomes something he is not. Modern-day football managers, who are under constant pressure to get results, lest they get the sack, are understandably drawn towards forms of attacking play that involve organised collective discipline (such as counter-pressing) because it's something over which they can exert control, whereas the reliance upon the individual brilliance of a single player is fraught with greater levels of risk. This largely explains why the number ten has become such an endangered species and the decline in the importance of the number ten role corresponds quite closely with the decline in the numbers of street footballers too. The same commercial pressures which drive the reduction in various forms of risk-taking on the pitch also shape the trend of youth development towards the quarantining of young footballers in youth academies at ever younger ages, where they can be subject to greater levels of adult supervision and managerial control.

CONCLUSION

Street footballers like Diego Maradona, who helped turn football into a huge global economic empire by invigorating interest in the game among a whole new generation of young people, due to the exciting nature of their play, are no longer considered to have a role to play due to the commercial pressures which they unwittingly helped to set in motion. In the cut-throat/competitive world of modern professional football, the Diego Maradona-esque, street-footballing number ten is deemed to be too chaotic/unpredictable for a world which seeks predictability/order in the relentless grind for instant/constant results. The outcome is a game that is more structured/ordered but also one which is more predictable and less exciting. In my last Substack post I noted that the changes which have propelled the English Premier League towards becoming a financial behemoth were shaped by wider changes in the British economy that were reflected elsewhere in the restructuring of the political gravity of the country. Likewise, the direction that football has taken with respect to the enclosure of young boys into youth academies at younger and younger ages, mirrors changes that have taken place in wider society too. The freedom which the street footballer once enjoyed to develop his idiosyncratic style independently have diminished — aside from the odd pocket here or there, such as the cage football scene in South London, the Pelada of the Brazilian Favela and the Ballon sur Bitume of the Banlieues of Ile-De-France — and these diminished freedoms to engage in independent play have their echoes in the diminished opportunities for free, independent, unstructured, outdoor play for young children in general. A subject which I will focus on in a future Substack post. Football, in one sense, is a business, and in any business, the most important thing is the bottom line, but football is also a form of play, to be enjoyed for its own sake, and the decline of the street-footballer indicates that we are in danger of losing touch with why we all fell in love with football in the first place.

Thats very interesting. Im not very knowledgeable about basketball but I find it fascinating that some of the changes that have happened in football have also occurred in other sports too. Thank you for taking the time to read the blog I wrote and also to comment. I appreciate it.

The same process of analysis and rationalization that has neutered the playstyle of football has operated too on basketball, with similar results. Just as football is now dominated by the efficiencies of gegenpressing and midfield athleticism to the detriment of 'wizardry', so basketball is dominated by floor spread and the three-point shot, to the detriment of every other aspect in the game.

If one's objective is to win, both are clearly the superior style to their alternatives, but it has robbed both sports of much insouciant joy.