MAN, THE PROVIDER

DEINDUSTRIALISATION AND ITS DISCONTENTS

“You know what the trouble is, Brucey? We used to make shit in this country, build shit.”

Frank Sobotka. The Wire.

INTRODUCTION

In the grand sweep of human history, one could argue that three seismic transformations have radically reshaped gender roles. The first was the Agricultural Revolution, which gave rise to settled societies and entrenched patriarchal structures that privileged men in both economic and social life. The second was the Industrial Revolution, which sharply divided the spheres of labour—casting men as breadwinners and women as domestic caregivers, institutionalising a rigid gender binary. Most recently, deindustrialisation—the Post-Industrial Revolution—has upended this arrangement. Men with lower levels of human capital have now lost their comparative advantage. Simply put, technological progress has steadily displaced manual labour, diminishing the economic value of physical strength. In its place, the labour market increasingly rewards cognitive and interpersonal skills—traits more closely tied to formal education. As a result, the comparative advantage once held by men without academic credentials has eroded. Consequently, men with lower levels of human capital are disproportionately disadvantaged by this new economic settlement, and subsequently struggle to find a clear role in what is now a service-based economy. The fall-out of deindustrialisation, and its impact on such men in particular, is the subject matter of this blog.

MAN, THE PROVIDER

For much of human history, masculinity was defined by clear societal roles: being a provider, protector, and authority figure — roles rooted in economic necessity and cultural tradition. One of the key messages of the recent deluge of books on the theme of the crisis of modern manliness is that ‘masculinity’ is a social script that one has to be acculturated into. For the vast majority of human history that ‘script’ was never in doubt. The essence of this ‘script’ is best distilled by the fictional character Gus Fring (of all people) in the American TV drama ‘Breaking Bad’:-

‘A man provides. And he does it even when he's not appreciated, or respected, or even loved. He simply bears up and he does it. Because he's a man.’

For all the problems with this worldview, it has the advantage of clarifying what is expected of men and providing a much needed sense of purpose. This sense of purpose appears to be severely lacking for many young men today and the statistics sadly bear this out. The ‘Centre For Social Justice’ reports that since the pandemic alone, the number of British males aged 16 to 24 who are NEET (not in employment, education or training) has increased by 40% compared to just 7% for females. They also report that in the past young women were more likely to be NEET than young men, but now young men were more likely to be unemployed. Young men now make up two-thirds of the unemployed in that age-group. Neil O’Brien reports that there are almost 1M young people not in education, employment or training and that 1 in 10 working age adults are not in work because they are unemployed or long term sick.

DISABILITY CONCEPT CREEP

As the world of work has contracted—through automation, outsourcing, and the rise of precarious, low-status employment—disability diagnoses have proliferated. In part, this may partly reflect improved recognition of conditions once overlooked. But it also suggests a deeper structural shift: when stable, dignified work becomes scarce, more people are classified (and come to see themselves) as unfit for participation in the labour market. In this way, the expansion of diagnostic categories functions not only as a medical phenomenon but as a social response to the narrowing of economic opportunity.

From man, the provider, to man, the pathologised. As traditional avenues for stable, meaningful work have eroded, especially for working-class men, diagnostic inflation—-to put things into perspective a majority of Brits now self-identify as ‘neurodivergent’—- has, in some cases (it can be argued,) replaced vocation. What was once a role rooted in economic contribution—-man, the provider—- is now increasingly framed through therapeutic or pathological terms. In this landscape, ‘disability’ becomes not just a clinical label but a coping mechanism for a society that no longer knows what to do with its increasingly economically inactive population.

{link}

The latest estimates indicate that 16.1 million people in the UK were classed as having a ‘disability’ in the 2022/23 financial year. This represents 24% of the total population, up from a mere 17% only ten years ago. We now spend £65 billion a year on sickness benefits—25% more than in 2019—which is more than the £60 billion we spend on the defence budget and the £20 billion we spend on the police.

It can be argued that diagnostic inflation has spread, extending far beyond the workplace, to encompass school-children, many of whom risk being labelled before they’ve even had a chance to fail—or succeed—on their own terms. What began as a means to protect the vulnerable now risks pathologising ordinary struggles. 40.5% of all pupils in state schools in Scotland are classed as having additional support needs. Almost eight times the number when the additional support for learning act was introduced in 2004. Nearly half of people born in Wales in 2002-2003 were classed as having special educational needs. The Institute for Fiscal Studies has reported that half of all school funding since 2015 has gone towards ‘special educational needs.’

REGIONAL INEQUALITY

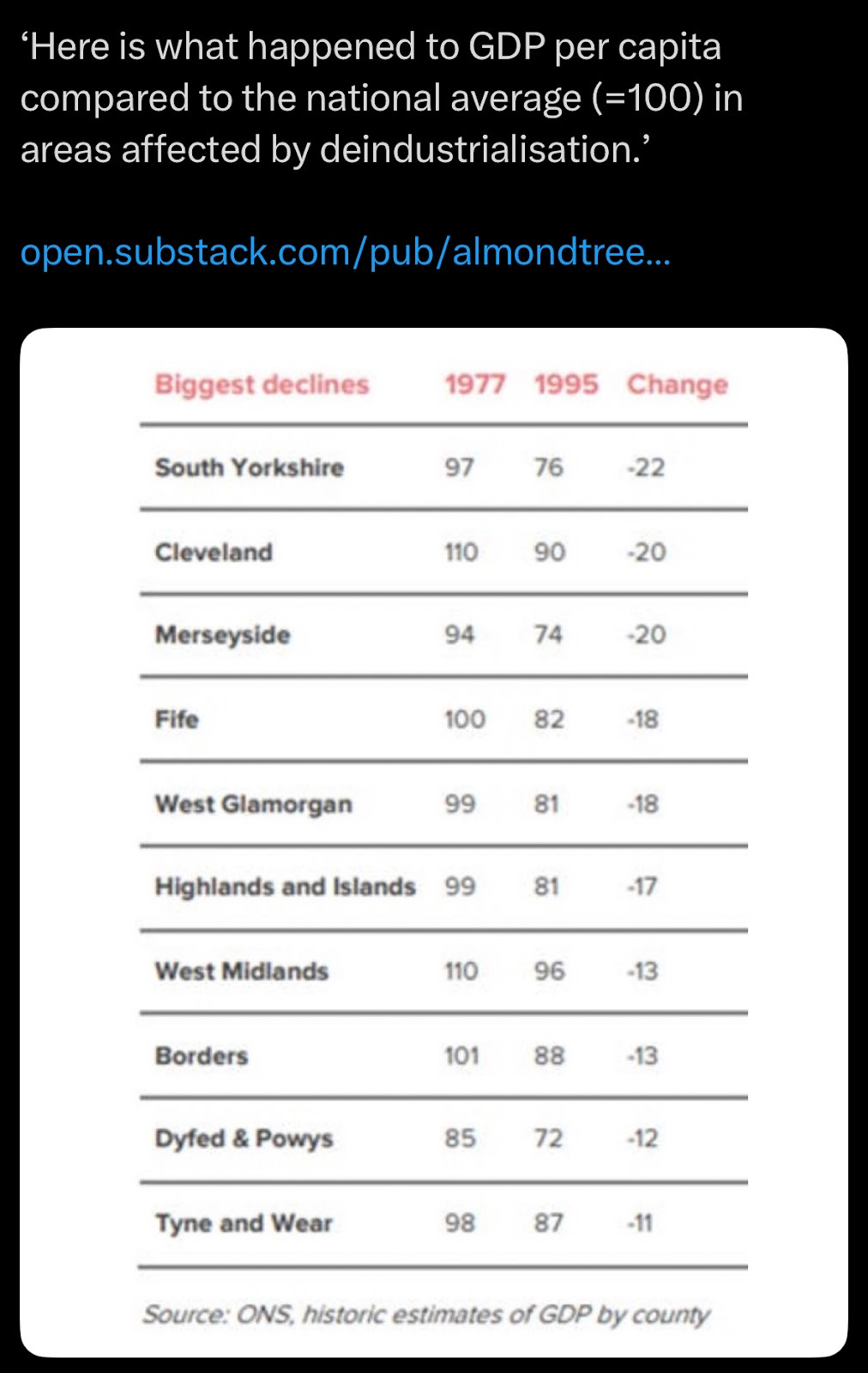

{link}

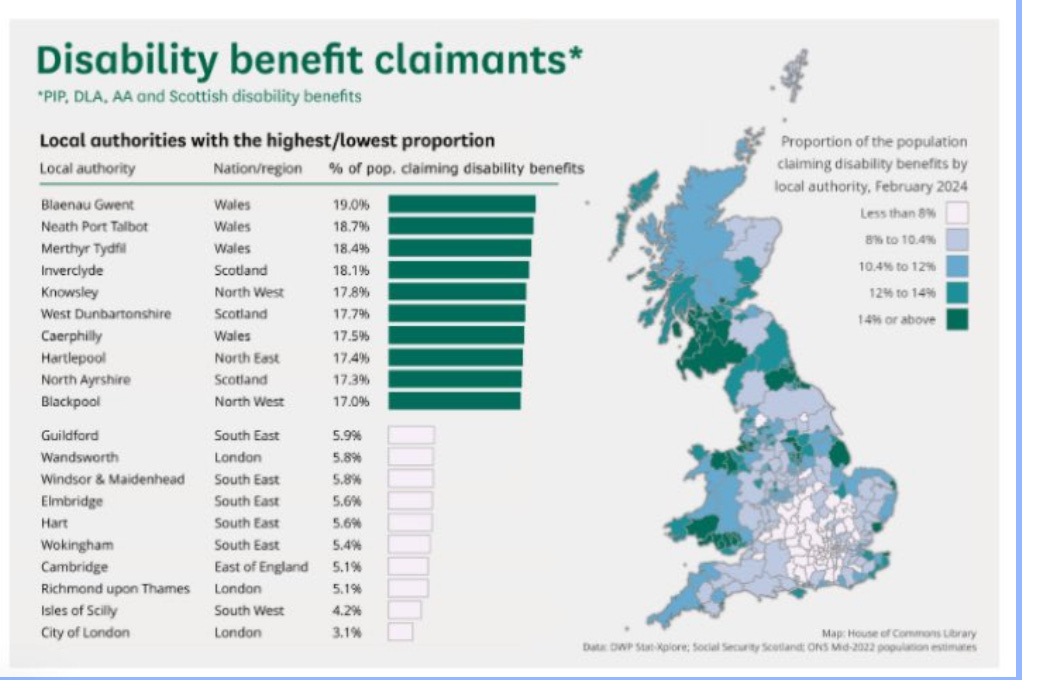

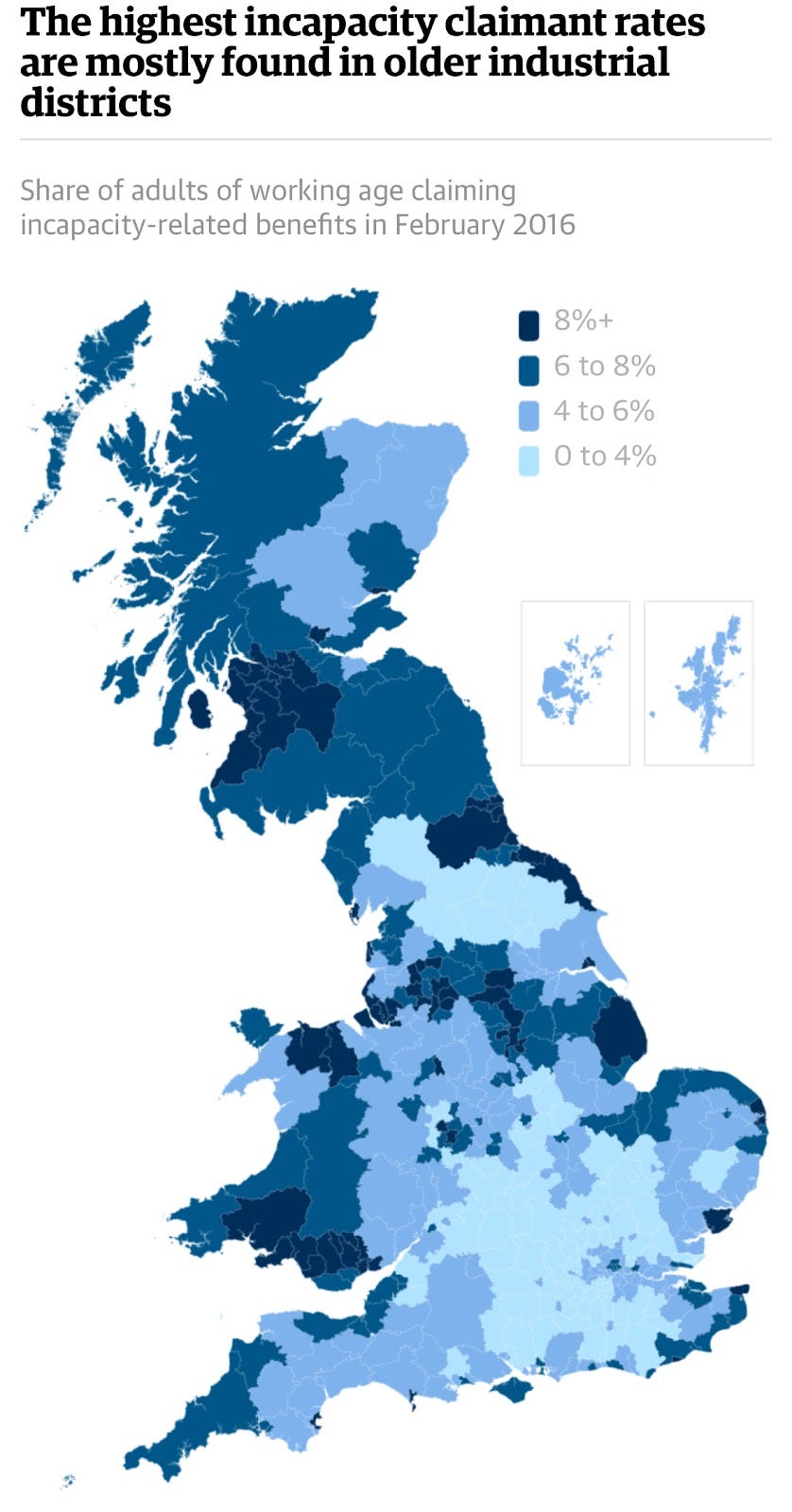

Unsurprisingly, disability benefit claimants are disproportionately in deindustrialised areas. A 2016 report noted that about three-quarters of UK districts with the highest DLA/PIP claimant rates were in deindustrialised areas. These findings indicate that deindustrialisation doesn’t just affect employment—it also shapes how disability benefits are used. In areas where stable manual and manufacturing jobs have vanished, people are more likely to transition into long-term illness or disability benefit systems. This suggests that policy responses need to address work opportunities, rather than framing it purely as rising medical need.

{link}

Regional analysis consistently shows that the collapse of manual industries—mining, steel, shipbuilding, and manufacturing—triggered a sharp rise in male economic inactivity across Britain’s deindustrialised heartlands. As these traditionally male-dominated sectors vanished, many men, particularly those with limited formal education, found themselves permanently detached from the labour market. In places like the North and parts of the Midlands of England, the loss of blue-collar jobs wasn’t replaced with comparable employment, leaving a vacuum in both income and identity. For many, it can be argued, claiming incapacity or disability benefits has become the default response—not always due to medical necessity alone, but also because these benefits have offered some modicum of financial stability. Over time, this shift has arguably blurred the line between illness and unemployment, transforming welfare systems into mechanisms for managing the fallout of economic collapse—particularly among working-class men. All in all, the percentage of the population who receive more in benefits than they pay in tax in this country has now hit 53%.

Deindustrialisation and computerisation have stripped working-class men without university degrees of their historical labour market niche. Where physical skill and routine competence once ensured steady work, today’s economy increasingly rewards credentials, cognitive flexibility, and interpersonal fluency—traits cultivated through formal education. As traditional male jobs vanished, many men found themselves not only unemployed but unemployable in this emerging economy. This mismatch, one could argue, has helped fuel a surge in disability claims, especially in former industrial regions, where diagnostic inflation can mask structural redundancy. The result is a quiet crisis of demoralisation and drift, feeding political disaffection and deepening distrust in institutions that promised meritocracy but delivered marginalisation. Meanwhile, education policy continues to valorise academic pathways while failing to offer enough in the way of serious vocational alternatives, compounding the sense of exclusion among those left behind.

{link}

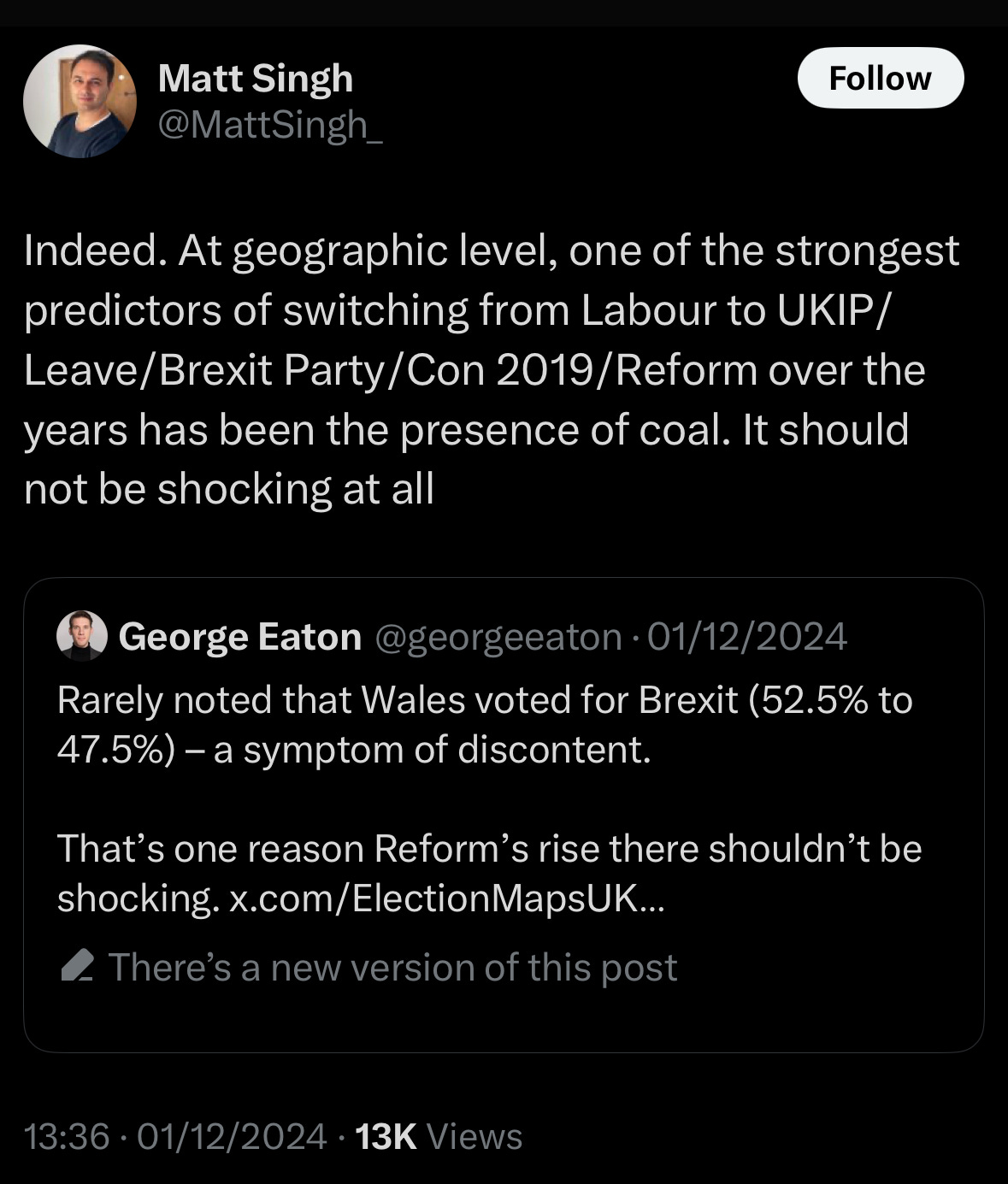

As traditional male employment collapsed under deindustrialisation and computerisation, many working-class men—particularly those without university degrees—were left economically adrift and culturally disoriented. Disability claims, welfare dependency, and long-term inactivity became widespread in former industrial heartlands. But these weren’t just economic shifts—they were identity shocks, eroding masculine roles built on work, provision, and social utility. Into this void stepped right-wing populism, offering not just scapegoats—immigrants, elites, ‘wokeness’—but a sense of grievance with moral clarity. It reframed economic marginalisation as cultural betrayal, turning forgotten workers into the wronged nation. In this way, structural job loss translated into political rage, and social exclusion became a rallying cry.

RIGHT-WING POPULISM

In Britain, the collapse of heavy industry and the shift toward a service-based, credential-driven economy hit working-class men hardest—particularly in the North, Midlands, and parts of Wales and Scotland. As manual jobs disappeared and no equivalent roles emerged, many men without degrees slipped into long-term economic inactivity, often via disability benefits. But the impact wasn’t just material; it was existential. The role of ‘man as provider’ eroded, and with it, a sense of identity, purpose, and status. Labour’s retreat from its traditional base, coupled with a political class increasingly seen as metropolitan and unresponsive, created fertile ground for right-wing populism. UKIP and later the Brexit Party and Reform have harnessed this disaffection, framing it as a revolt not just against Brussels but against a liberal elite that had written off large swathes of post-industrial Britain. Brexit thus a proxy for deeper grievances: perceptions of cultural loss and economic abandonment.

In Britain, right-wing populists have disproportionately mobilised men without degrees from deindustrialised regions—a pattern first evident with UKIP in former industrial towns, and continuing now with Reform UK. Recent analysis shows that in the 2024 general election, non-graduates were over twice as likely as graduates to back right-wing populist parties, especially in regions marked by low income, deindustrialisation, and educational underachievement.

Regional inequality, deindustrialisation and the rise of right-wing populist parties are not separate trends but facets of the same phenomenon. The long-term economic hollowing-out of Britain’s industrial heartlands has entrenched geographic disparities while simultaneously creating a pool of economically adrift men whose loss of work has also meant a loss of status, purpose, and identity. This has dragged the political gravity of the country in a right-wing populist direction, as cultural grievance fills the vacuum left by economic dislocation. Populist movements have successfully channelled this disaffection, reframing structural decline as betrayal by distant elites, fuelling a politics of resentment rooted as much in place and identity as in income.

ASSORTATIVE MATING

Deindustrialisation hasn’t just reshaped the economy—it’s disrupted family formation, too. As stable, well-paid working-class jobs disappeared, men without higher education became less ‘marriageable’ in economic terms. Due to assortative mating/social homophily—where people tend to partner within their own social strata—this led to a growing mismatch in the partner market. The result has been a rise in delayed or foregone partnerships, especially among economically insecure men, contributing to higher rates of single-parent households in deindustrialised regions. This shift carries well-documented knock-on effects: reduced household stability, poorer child outcomes, an increased risk of child abuse, mental health issues, and a range of other behavioural problems.

Deindustrialisation didn’t just destroy jobs—it destabilised a cultural script. For generations, the role of man as provider anchored working-class masculine identity. Economic contribution wasn’t just about income; it was the bedrock of male status, purpose, and social legitimacy. Richard Reeves describes masculinity as a social script—a set of expectations about what it means to be a man in a given society. In industrial Britain, that script was clear: work hard, provide for your family, be dependable. But as manufacturing collapsed and the economy shifted toward credentialed, service-based labour, that script frayed—especially for men without university degrees. With fewer paths to economic utility, these men became less ‘marriageable’ in a society where women increasingly sought partners with economic and educational parity (assortative mating). The result has been a marked decline in stable family formation, particularly in deindustrialised regions. Rising rates of single-parent households, male social withdrawal, and community breakdown are not just demographic trends—they are symptoms of a deeper erosion of masculine identity. In the absence of a viable provider role, many men are left un-moored, their place in both the economy and the family uncertain.

FEMALE HYPERGAMY

Deindustrialisation has quietly intensified a pre-existing social dynamic: female hypergamy—the tendency for women to seek partners of equal or higher socioeconomic status. In a post-industrial economy, where stable, well-paid jobs for non-graduate men have largely vanished, this dynamic produces sharp asymmetries in the “relationship market.” As men in left-behind regions become less economically viable as providers, many women opt to delay or forgo long-term partnerships altogether, contributing to rising rates of single parenthood.

Unlike in the past, when even low-skilled men could earn a family wage in sectors like mining, manufacturing, or logistics, today’s economy prioritises educational credentials—an area in which women now increasingly outpace men. This has created a mismatch in relationship expectations. The result is fewer marriages among working-class communities. Personal dysfunction as a structural outcome of economic decline. In deindustrialised regions, children are more likely to grow up without stable father figures, contributing to a host of interlinked challenges: lower educational attainment, poorer mental health, and cyclical disadvantage. What begins as labour market disruption ends as social disintegration, as the economic basis for traditional family formation collapses and no clear replacement emerges. Left unaddressed, this dynamic risks embedding long-term demographic and social instability in Britain’s already marginalised post-industrial communities.

MANAGED DECLINE

{link}

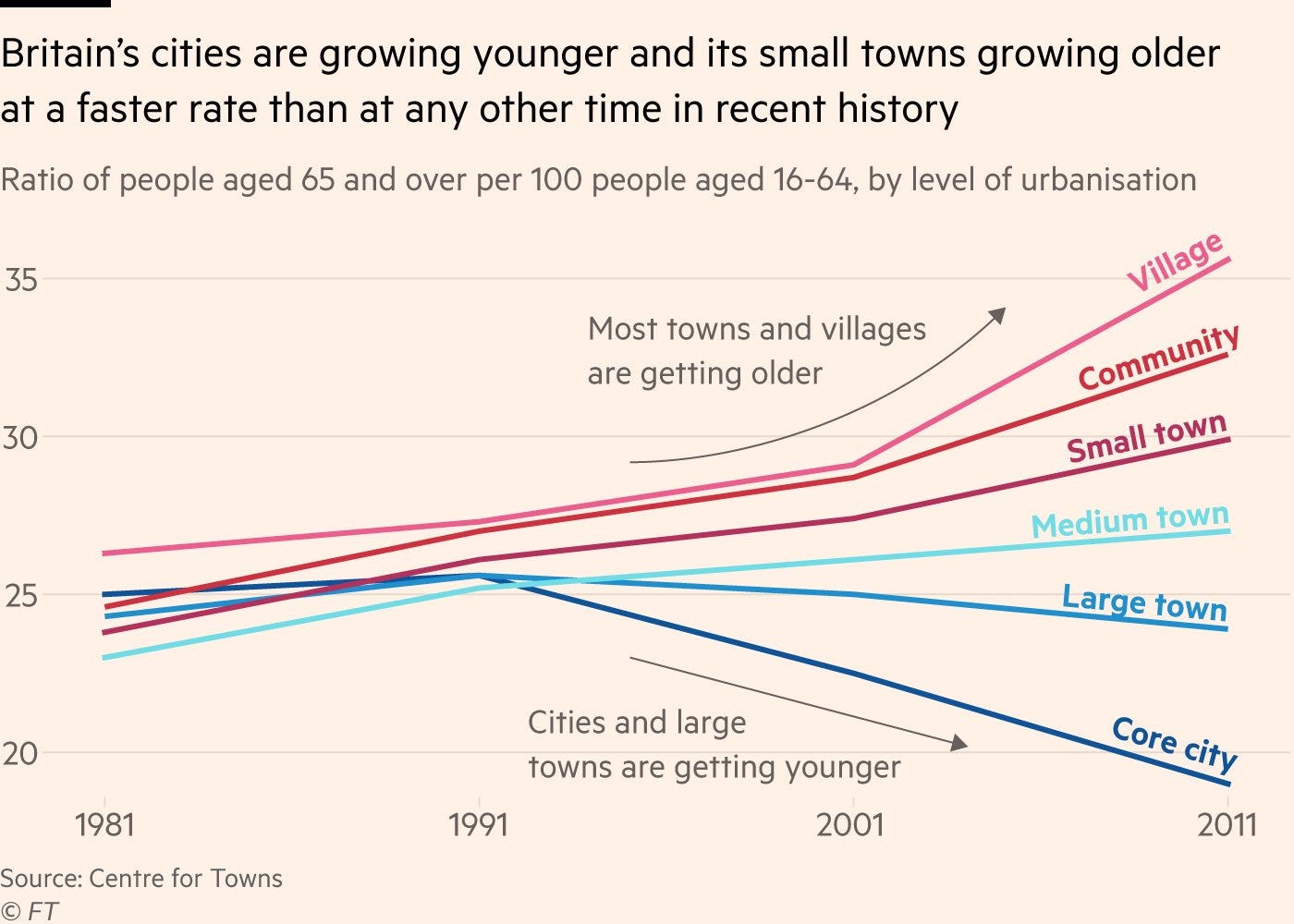

We are left with two choices: reindustrialisation—to provide economic renewal, social stabilisation and political re-calibration— or managed depopulation. If the economic base of post-industrial regions is not rebuilt, then the only alternative is a slow demographic hollowing-out as younger, educated people migrate to more prosperous urban centres, leaving behind ageing, economically inactive populations, frayed social infrastructure, and deepening inequality. Reindustrialisation—whether that be through green energy, advanced manufacturing, public investment in infrastructure or via other means—offers a chance to restore not just jobs, but dignity and purpose, particularly for men whose social role was once bound up with stable, manual work. But it requires long-term commitment, state capacity, and a rejection of the assumption that Britain can thrive on services and finance alone.

{link}

Depopulation, by contrast, may make economic sense on a spreadsheet, but it carries weighty social and political consequences. It signals surrender: that entire towns and communities have no future. This risks fostering resentment, alienation, and the very cultural grievances that can fuel the flames of right-wing populism. Either path demands a reckoning with what kind of country we want to be—one that reweaves the social fabric of its neglected regions, or one that quietly lets them wither while blaming their despair on personal failure rather than structural abandonment.

In the absence of meaningful reindustrialisation, Britain is drifting into a de facto policy of managed depopulation, where public investment, talent, and infrastructure are concentrated in London and the South-East, while large swathes of the English North, Wales and Scotland quietly hollow out. This risks not just economic loss, but social and political destabilisation, as entire communities are left to feel abandoned by a state that no longer sees them as viable.

{link}

CONCLUSION

Britain’s post-industrial landscape tells a deeper story than just economic decline—it marks the unravelling of the traditional male role as provider. Deindustrialisation didn’t just destroy jobs; it dismantled a social script that anchored identity, status, and family formation for generations of working-class men. Stripped of stable work, many have become economically adrift and socially marginal, less likely to marry, more likely to disengage, and increasingly clustered in regions marked by welfare dependency and political alienation. Right-wing populism has capitalised on this void, offering a language of grievance where mainstream politics offers silence or technocratic drift. Britain now faces a stark choice: commit to meaningful reindustrialisation that restores economic dignity and social stability—or continue down the path of managed depopulation, with all the demographic, familial, and political consequences that follow. What’s at stake is not just economic renewal, but the re-knitting of purpose and belonging for men left behind.