‘Humans evolved to live in small social groups; perhaps no more than 50 to 120 people formed a Palaeolithic clan and probably most clans were smaller. But now we live in enormous aggregations—sometimes tightly packed in small boxes piled on top of each other. We have social hierarchies and a mixture of interactions well beyond our evolved experience. How well are our brains matched to these challenges? To what extent might some mental illness be a reflection of a mismatch between our evolved brains and these dramatic social changes? There is a growing and respected school of psychologists who believe that such a mismatch is indeed fundamental to the ecology of mental illness.’

(Peter Gluckman and Mark Hanson)

‘There is wildness in us all, but in most of us it’s latent, sleeping, unused. Wild we are in our deeper selves: we are hunter-gatherers in suits and dresses and jeans and T-shirts. We have been civilised – tame – for less than 1 percent of our existence as a species.’

INTRODUCTION

Jonathan Haidt, in his influential book ‘The Anxious Generation,’ has written that ’the Great Rewiring of Childhood, in which the phone-based childhood replaced the play-based childhood, is the major cause of the international epidemic of adolescent mental illness.’ I take issue with this thesis on a number of levels (as I explain in depth in two previous Substacks blogs here and here and which I also elucidate in two ongoing Twitter mega-threads here and here.)

Firstly, I take issue with the idea that smartphones are a cause of mental illness. The idea that ‘social media use causes young girls to develop mental health problems’ in my opinion is just the ‘computer games causes young boys to become violent’ of the current era. A moral panic rather than serious social science.

Secondly, I also take issue with the level of certitude people evince in the idea that there actually has been an ‘international epidemic of adolescent mental illness’ in the first place. The erroneous idea that vaccines cause autism arose initially because autism rates had increased rapidly in a short space of time. What the anti-vaxxers did not appear to understand or accept was that autism diagnosis rates had increased because autism was redefined to capture a bigger group of people. The idea that smartphones and social media use cause child/adolescent mental illness is, I believe, a similar story.

Any analysis of the prevalence of functional mental illness which doesn’t fully grapple with the fact there are no definitive biomarkers and that they are defined literally by committee and are therefore subject to change due to diagnostic fads, and lobbying by patient consumer groups, isn’t worth the paper it's written on. This doesn’t mean that mental illness is a myth but it does mean that the parsimonious explanation for reported increases in rates of mental illness is always more likely to be diagnostic expansionism rather than exogenous shocks (such as the introduction of the smartphone.)

The mistake that Haidt and others make is to fail to fully grasp the inherent elasticity of Psychiatric concepts and therefore to assume that the rise in the reported prevalence of mental disorders must have been caused by an exogenous shock. The history of Psychiatry is littered with diagnostic fads that came and went—whither Neurasthenia or Hysteria?— which started within the walls of Psychiatric practice before breaking free and running wild in the popular culture. We should bear this in mind when analysing current trends rather than pursuing an ahistorical approach.

However, where I do agree with Haidt is with respect to his emphasis on the significance of the decline of what he describes as a ‘play-based childhood’ This is a real phenomenon with real-world consequences. Whilst I disagree with Haidt that this has been caused by smartphones, given that it is a trend which predates their introduction by a number of decades, I do agree that this loss of childhood independence is a significant societal trend with huge ramifications for the health and well-being of children and adolescents.

The decline of childhood independence and its ramifications are the subject of this blog. I posit the idea that we have created an evolutionary mismatch in which we evolved to live in one set of circumstances—spending lots of time outside with lots of access to greenspace, and lots of opportunities to partake in sufficient amounts of physical activity and to engage in free/unstructured play—but yet have contrived to live in a totally different set of circumstances without sufficient access to those things.

I posit that this is primarily due to car-centric urban design and intensive parenting styles geared towards the concerted cultivation of educational outcomes, trends which predate the introduction of the smartphone. I argue that this mismatch has created a number of problems and I borrow the concept of ‘rewilding’ from environmental conservation to make the case for a different conception of childhood development more conducive to meeting the needs of young people.

In this blog I am not substituting smartphone-use for a different cause of child/adolescent mental health problems. I'm not of the belief that we can ever be truly sure that there actually has been a genuine rise in mental health problems, given the inherent elasticity of Psychiatric concepts. My argument is simply that we evolved to thrive in one environmental milieu but have conspired to live in a completely different one and that this has consequences for our sense of well-being and life-satisfaction.

{link}

BIOPHILIA

The late American biologist E.O Wilson coined the phrase ‘biophilia’ to describe the theory that humans are hardwired to thrive in environmental settings similar to those in which humans evolved. As English conservationist Isabella Tree has put it: ‘We have been hunter-gatherers for 99% of our genetic history, totally and intimately involved with the natural world….The need to relate to the landscape and to other forms of life—whether one considers this urge aesthetic, emotional, intellectual, cognitive or even spiritual—is in our genes. Sever that connection and we are floating in a world where our deepest sense of ourselves is lost.’

There is a mountain of evidence that spending time in natural environments (greenspace, to use the correct social science parlance,) is beneficial for health and well-being. Access to residential green space in childhood is associated with a lower risk of psychiatric disorders from adolescence into adulthood. One Danish study found that growing up near vegetation is associated with an up to 55% lower risk of mental health disorders in adulthood. Residential exposure to vegetation is associated with reduced risk of depressive symptoms for young people.

There is evidence to suggest that nature characteristics such as vegetation cover and afternoon bird abundances are positively associated with a lower prevalence of depression, anxiety, and stress. People living within 100 metres of higher density of street trees have lower antidepressant prescription rates. Children who grow up in cities tend to have psychotic symptoms more often than children living in smaller towns and villages. Those raised in major cities were more than 40% more likely to report psychotic experiences, such as hearing voices and feeling extremely paranoid, than their rural counterparts. Natural surroundings in childhood are associated with lower schizophrenia rates.

Listening to birdsong can also help relieve feelings of fatigue and to concentrate better at school too. Furthermore, a study found that a 10% increase in the number of bird species in peoples' surroundings increased their life satisfaction by as much as an extra 10% in the bank. There is evidence that there is certain bacteria in soil that has similar properties to antidepressants. Higher residential surrounding greenness is associated with slower cognitive decline. Simply seeing nature, even through a window, appears to boost well-being. People who see trees, flowers and grass recover from surgery faster (and take fewer painkillers), than those with views of brick or concrete.

Greening vacant lots is associated with crime reduction. Prisons with more greenspace have lower rates of violence and self-harm. Buildings that looked out on trees and grass experienced about half the violent crime level of buildings that looked out on barren courtyard. The less green the environment, the higher the rate of assault, battery, robbery and murder. The more tree cover around a school, the better its standardised test scores in both reading and maths.

Spending more time in natural environments is associated with enhanced levels of creativity and with greater psychological well-being. Living in areas with higher amounts of green spaces is associated with reduced mortality, particularly from cardiovascular disease, and lower rates of hospitalisation for people with neurodegenerative diseases. Visits to parks, community gardens and other urban green spaces is associated with lower use of drugs for anxiety, insomnia, depression, high blood pressure, and asthma.

The higher maternal residential greenness, the lower risks of congenital heart defects in infants. There is evidence that greener play areas and childhood exposure to outdoor microbes can boost children’s immune systems. There is also evidence of inverse association between surrounding greenness and all-cause mortality.

{link}

DENSITY DIVIDE

I could go on and on, but the list of relevant research examples which point towards the powerfully restorative effects of spending time in natural environments are endless. It is not a huge surprise therefore that studies have found that the longer you spend in an urban environment during childhood and adolescence the higher your risk of developing mental illness in adulthood.

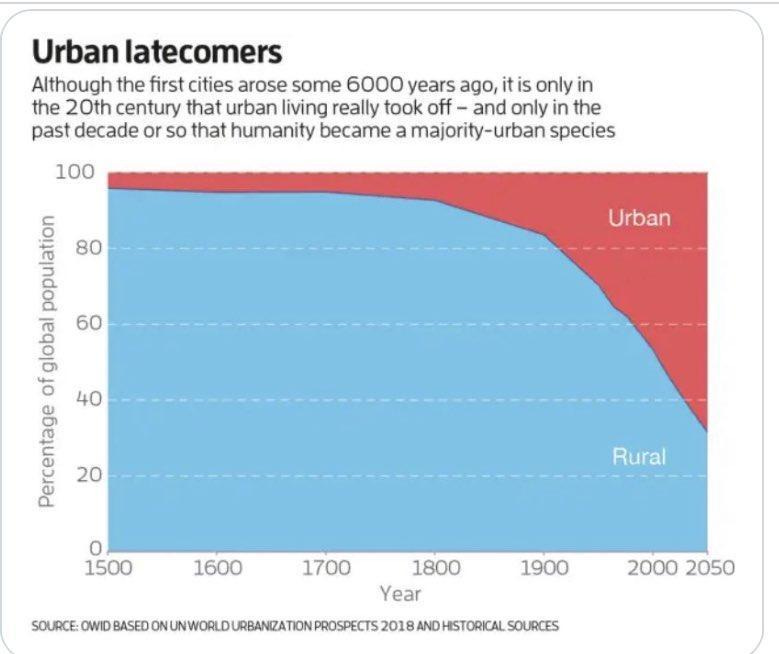

We take urbanisation for granted but as recently as 1805 barely 5% of the global population was urbanised, in 1950 it was still only 30%, and only in 2015 was it the case that more than half of the global population lived in urban environments. Human beings have been anatomically modern for roughly 200,000 years, but only in the last 9,400 years have we, and then only a tiny minority for the vast majority of that time, lived in towns and cities. City and town dwellers are exposed to more pollution, they have less access to greenspace, they get less exercise and they are also lonelier too. Research indicates that people who live in dense urban areas, particularly those with closely packed apartments, are more likely to experience loneliness and that the density of social connections is lower in cities. Unsurprisingly then, London, the most densely populated part of the UK, is also the loneliest.

The risk of developing depression has been estimated as 20% higher in urban dwellers than those who live outside the city, the risk of developing generalised anxiety disorder, 21% higher, and the risk of developing psychosis, 77% higher. Increased population density in general, such as you would be more likely to find in urban locales, is associated with lower levels of well-being.

There are a number of reasons why this might be the case, pollution could be one partial explanation, for instance, another is exercise. It stands to reason that the more time you spend outdoors, the more likely you are to engage in physical activity and the studies bear this out. Residential greenness is associated with increased physical activity and reduced obesity. One study found that people who lived furthest from public parks were 27% more likely to be overweight or obese. Whilst another found that living in a neighbourhood with more trees was independently associated with more free-time physical activity.

There is a huge amount of evidence that exercise is beneficial for our mental health, especially among adolescents. Adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines among adolescents is related to lower odds of suicidality in older boys. Replacing 60 mins daily sedentary behaviour with light activity at ages 12, 14, and 16 associated with 12-16% lower anxiety scores at 18. After adjusting for socio-demographic factors, greater frequency of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity is associated with lower depression symptoms.

There is plenty of evidence that teens who play team sports are generally happier and healthier too. Our nomadic ancestors had plenty of opportunities for exercise and this is reflected in studies of modern-day hunter-gatherers. Perhaps not coincidentally, the children of hunter-gatherer tribes exhibit lower levels of Psychiatric symptoms than the children and adolescents of modern, industrialised societies.

{link}

CAR CULTURE

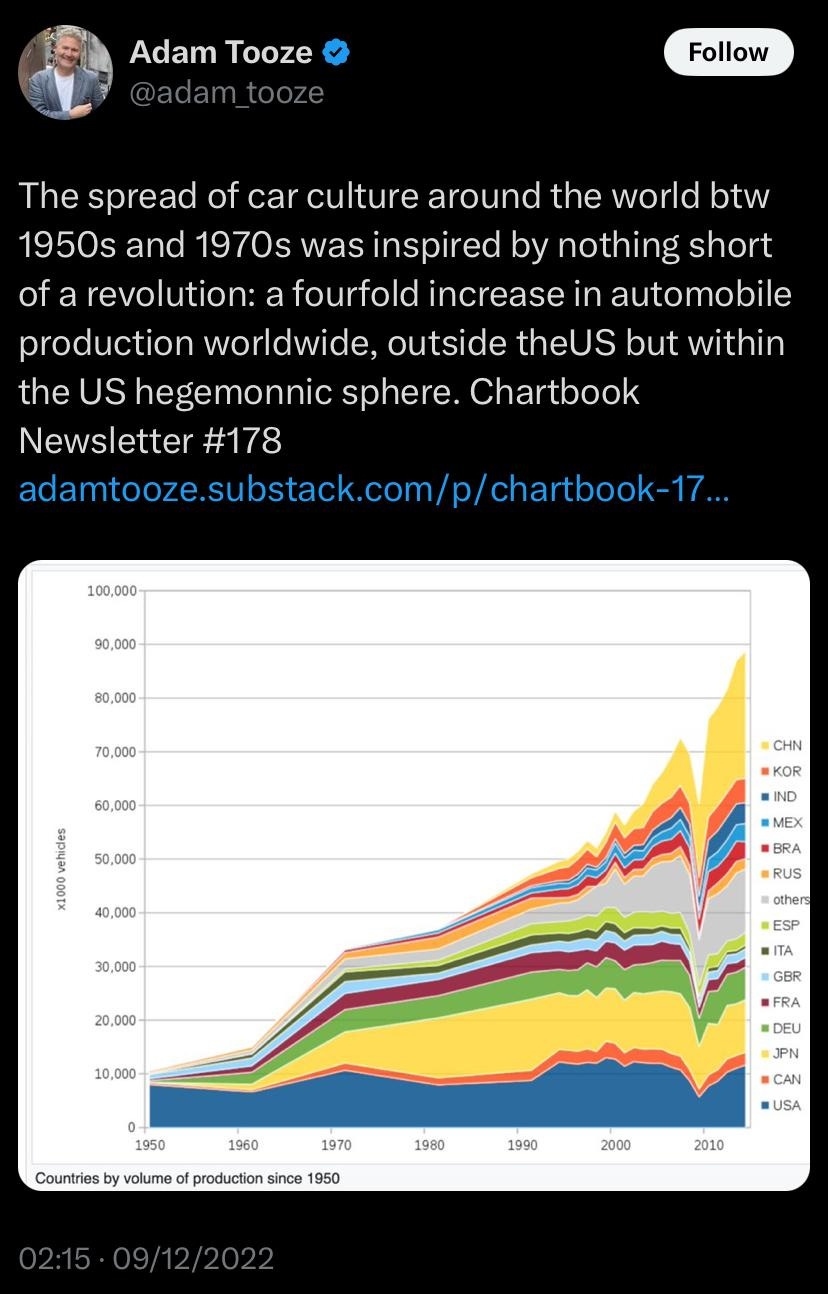

Opportunities for children/adolescents to exercise are more restricted in modern, urban environments designed around cars rather than pedestrians. Children walk less the more cars there are in a household and so have less independence. Studies have found that increasing traffic was the one factor above all others that restricted the development of children's spatial range. Since WW2, many cities have been outgrown by their surrounding suburbs, and as suburban sprawl has extended outwards, the number of cars has correspondingly increased. Urbanists have long argued that transportation technologies determine urban form and that modern suburban sprawl is a child of car-culture.

The widespread adoption of the car and the choice we have made to redesign our towns and cities around them have had far-reaching consequences. Ten minutes extra daily commuting time reduces involvement in community affairs by an average of 10%. People who endure more than a forty-five-minute commute were 45% more likely to divorce. The more time that people in any given neighbourhood spend commuting, the less likely they are to play team sports, hang out with friends, watch a parade, or get involved in social groups.

The effect of long-distance living is so strong that a 2001 study found that neighbourhood social ties could be predicted simply by counting how many people depend on cars to get around. The more neighbours drove to work, the less likely they were to be friends with one another. Charles Montgomery, in his book ‘Happy City,’ has written that people who live in mono-functional, car-dependent neighbourhoods outside of urban centres are much less trusting of other people than people who live in walkable neighbourhoods where housing is mixed with shops, services and places to work. They are also much less likely to know their neighbours, get involved with social groups, to participate in politics, answer petitions, attend rallies or join political parties or social advocacy groups.

Traffic danger is one of the main reasons that children don’t play outside like they used to. In Great Britain, research has found that children today play outside on average slightly more than 4 hours per week, compared to 8.2 hours for their parents' generation. British children are not allowed to play outside until two years older than their parents' generation, most children now turn 11 before they can play outside unsupervised. It has even been reported that three-quarters of UK children spend less time outside than prison inmates and the decline of what Haidt describes as a play-based childhood has marched in lock-step with a withdrawal from nature—half of British children cannot identify stinging nettles, 65% wouldn't know what a blue tit is, 24% do not recognise conkers and 23% do not know what a robin looks like—as we’ve retreated into suburban enclaves designed around cars.

THE HAPPIEST KIDS IN THE WORLD

{link}

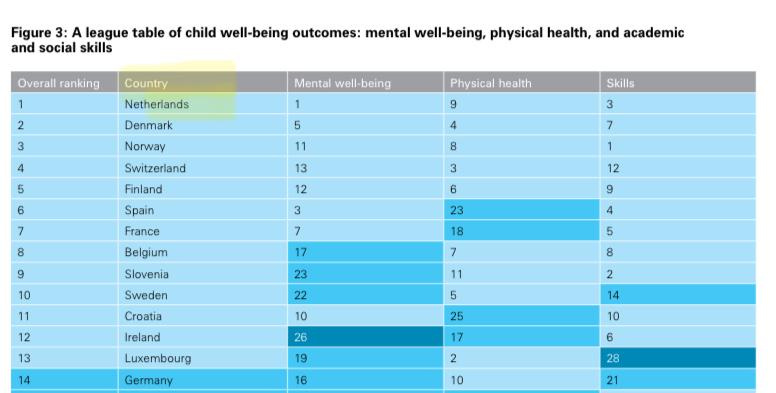

At the risk of contradicting my own argument, its important to point out that the Netherlands has long been one of the most urbanised parts of Europe but also reportedly has the happiest children in the world too (not to mention some of the lowest levels of child obesity among industrialised nations.) In the most recent WHO study, 90% of Dutch girls and 96% of Dutch boys aged fifteen claimed ‘high life satisfaction. Perhaps not coincidentally, the Netherlands also has the planet’s highest percentage of people who regularly cycle. Active commuters are less likely to suffer from a range of negative physical and mental health outcomes than non-active commuters. Fully 27% of all trips in the Netherlands are made on bicycles, school buses are uncommon, as the vast majority of those high school children cycle to class, plus 95% of ten-to-twelve-year-old’s bicycle to school at least some of the time. Dutch residents are the most physically active on earth, getting 12.8 hours of exercise each week.The average Dutch person cycles about 1,098K per year.

{link}

Dutch parents encourage their children to be independent and do not hover over their children. This, in turn, helps to promote the freedom and well being of Dutch children. This relatively relaxed parenting-style is underpinned by national infrastructure committed to enabling children to spend time outdoors and to be independently mobile in a safe manner. This is important because children are happiest when they are playing outside. Dutch cycling culture is not due to innate or immutable characteristics inherent in the Dutch psyche but due to political decisions made in response to the 1970’s oil shock.

Therefore, it shouldn't be beyond the wit of countries like the UK to follow their example.Tellingly, there is little difference between the amount of time Dutch and British kids spend in front of screens despite the fact that Dutch children report being happier than British children do. A sign perhaps that we should stop chasing red herrings. One in three children aged under nine in Britain today do not even have a playground near their home, never mind Dutch-style cycling culture, not to mention the fact that local authorities and state schools have sold off over 10,000 playing fields since 1979.

The example of the Netherlands demonstrates that urbanisation itself isn't necessarily the problem when it comes to happiness, albeit it presents a different set of challenges, it largely depends upon which type of urban design we’re actually talking about. Simply put, urban design which helps to facilitate active commuting and enables children to be independently mobile and to play outside (independent of constant adult supervision) in a safe manner, will be more conducive to the health and well-being of children and adolescents than forms of urban design which do not.

{link}

HELICOPTER PARENTING

Suburban sprawl, and the car-culture which it produces—to put things into perspective, over the course of their lifetime, the average American now spends as much time in their car as they do outside and spend as much as 90% of their entire time indoors—are not the only reasons children have less freedom and independence to go outside and play on their own. Additionally, changes in parenting styles are contributing factors also. Intensive parenting styles—dubbed ‘helicopter parenting’ to capture the ways in which parents are now said to hover over their children, a style of parenting that features parents being more heavily involved in their children’s lives—have become far more prevalent over the last few decades.

{link}

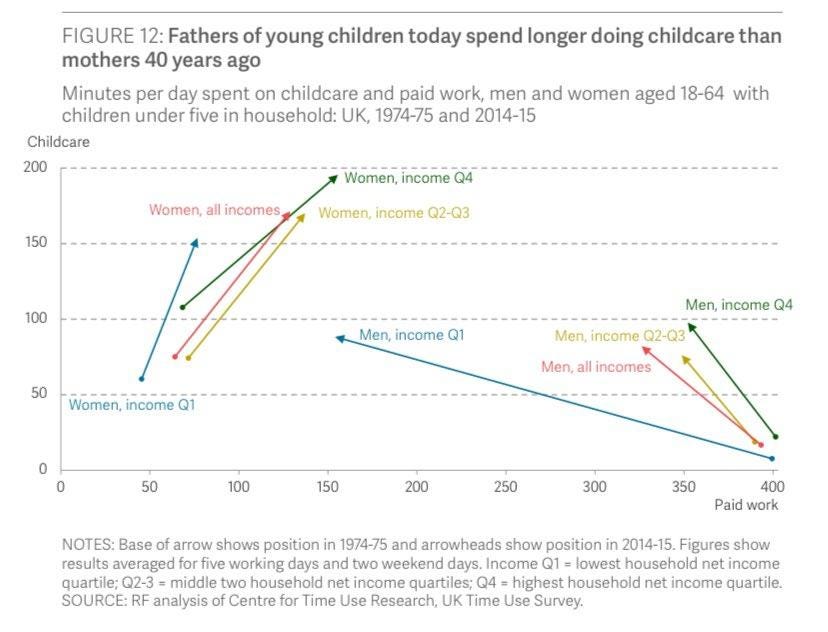

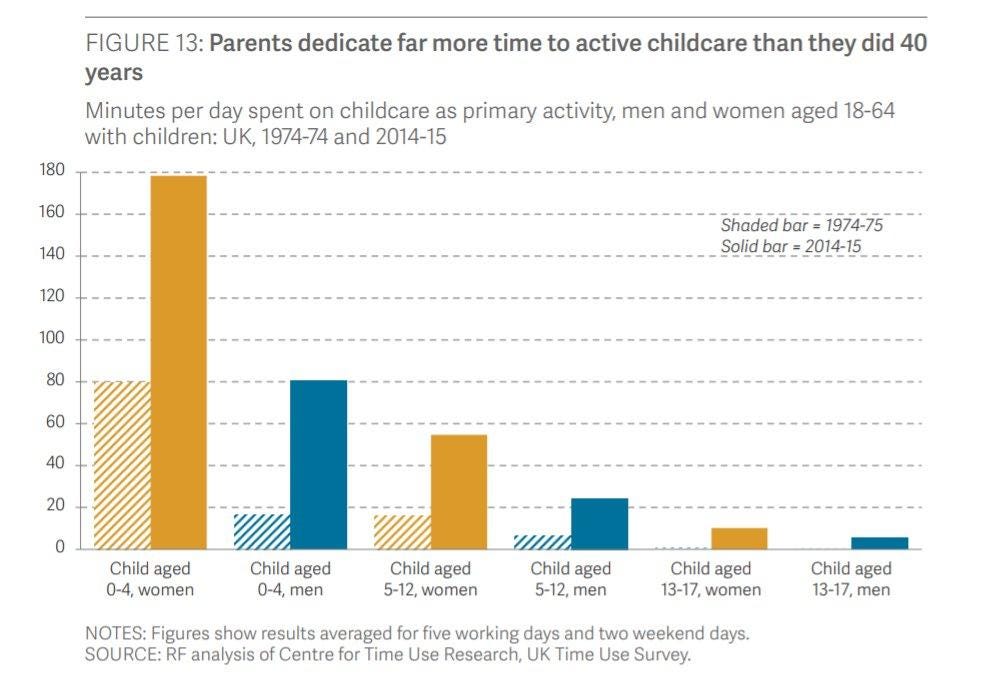

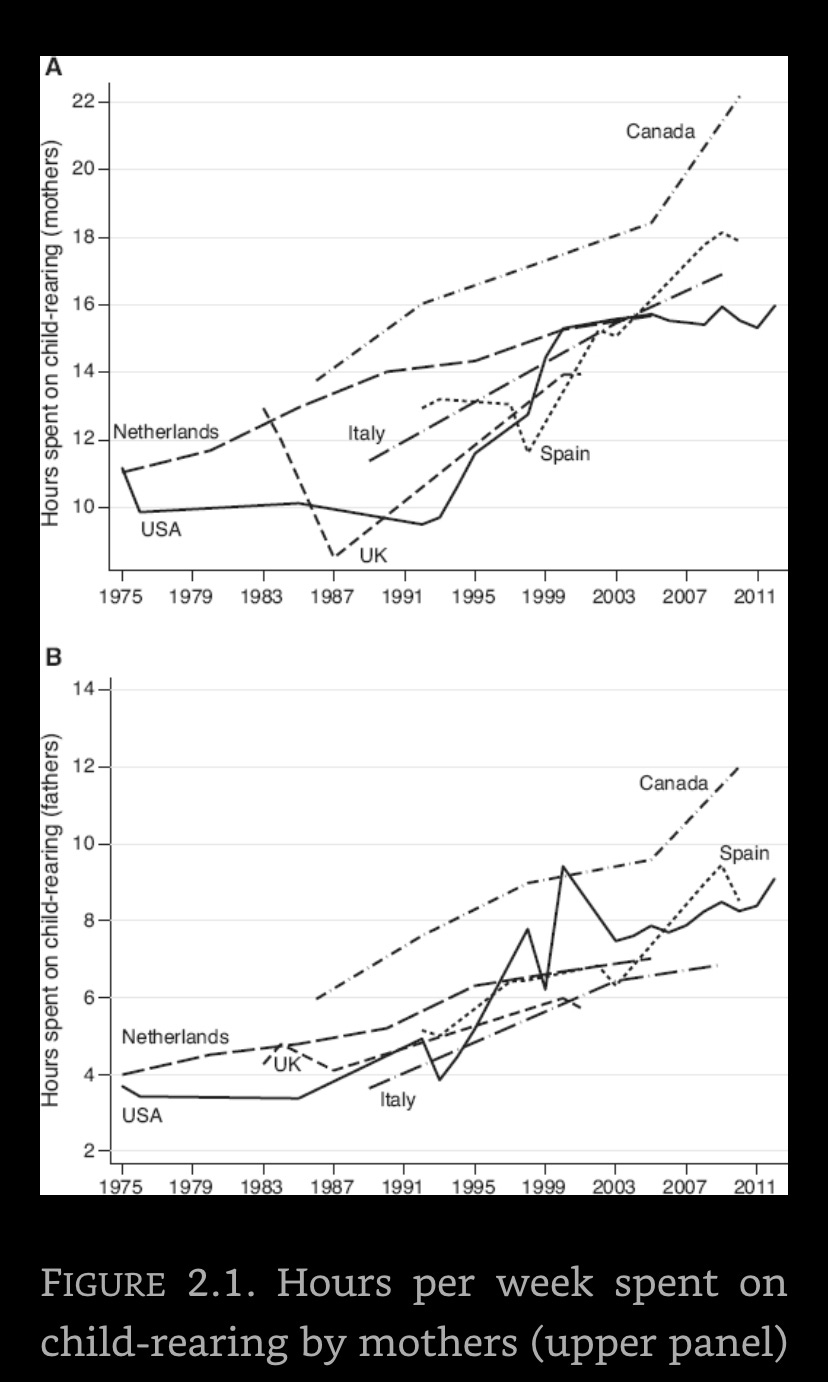

Some of the statistics on this are quite startling. Working mothers today devote more time to active childcare than stay-at-home mothers did in previous generations. Whilst fathers of young children today spend longer doing childcare than mothers did 40 years ago. Parents are now reportedly spending over 80% more time with their kids than they did in the 1970’s. This is an international phenomenon.

This rise in intensive parenting styles corresponds with other trends which indicates that younger generations are taking less risks than previous generations did and extending their adolescence for longer (if we conceive of adolescence as the transitional stage between childhood and adult independence.) Younger generations are now more likely to delay getting married and are having children later than previous generations did, they are also less likely to have a driver's license, to drink alcohol, to take drugs, to go on dates, to socialise with their friends, to even have friends, to have a summer job, to work for pay at all, to have a fight, to get pregnant, to have a boyfriend or a girlfriend, or to have sex, Put these changing adolescents trends alongside changing childhood trends which indicate that children have less freedom to roam than previous generations did, to be allowed to play outside independently, and to travel to school alone, and a definite pattern emerges.

Childhood has been enclosed and adolescence extended. Some of these trends—such as the decline of alcohol use among young people—are good—and some are bad—the decline of socialising with peers for instance—but it’s important to understand that both trends are inextricably linked. As Yuval Levin has put it:- there is less social disorder because there is less social life. The increase in intensive parenting styles is right at the heart of these changes. The decline of risky behaviours among young people is largely due to the decline in unstructured in-person socialising with their peer group and that is largely because of changes in parenting styles which has resulted in children/adolescents leading more sheltered and structured lives under the watchful eyes of their parents.

{link}

Why have parenting styles changed to become more intensive? It is partly as a result of declining fertility rates and technological changes, after all, the type of concerted cultivation of each individual child just wasn't as practical or feasible in an era before labour-saving devices and larger families because there literally wasn't enough time in the day (the relationship between intensive parenting styles and low fertility is likely to be bidirectional.)

In their book ‘Love, Money, and Parenting: How Economics Explains the Way We Raise Our Kids,’ economists Fabrizio Zilibotti and Matthias Doepke persuasively explain that intensive parenting styles have become more prevalent because they work. They work in the sense that they are associated with higher test scores and the higher educational attainment of children.

Doepke and Zilibotto demonstrate that when it comes to parenting styles, economics and culture are symbiotic. They show that in inegalitarian societies there is a greater parental emphasis on the importance of hard work in order to get ahead and that in modern, meritocratic societies—in which educational outcomes largely determine occupational opportunities and life chances—this emphasis on the importance of hard work is laser-focused on educational attainment in particular. In terms of parental styles, in combination with other factors, Doepke and Zilibotto explain that ‘the increase in inequality raises the stakes in parenting: parents will be more concerned about their children's position on the social ladder and hence have an incentive to invest more. This can explain why the rise in economic inequality has been accompanied by more intensive parenting overall.’

{link}

DIPLOMA DIVIDE

Intensive parenting styles have become more prevalent because they work. They work in the sense that they are associated with better educational outcomes on the part of children, and as inequality has risen, and the returns to education have grown, the incentives to invest more time in childcare has risen accordingly.

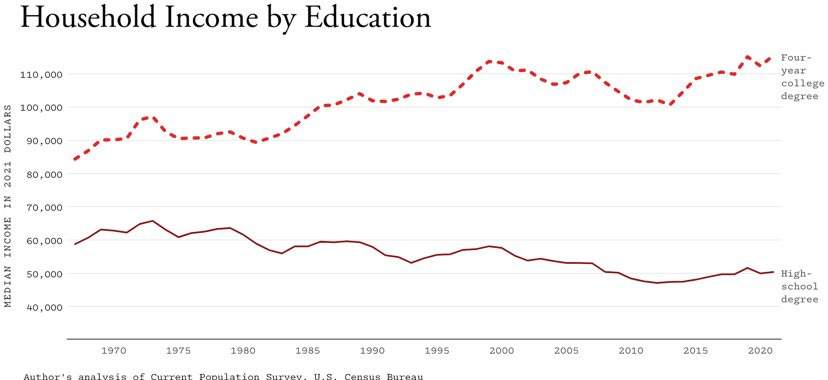

The returns to education have increased because, to quote economist David Autor:- ‘By making information and calculation cheap and abundant, computerization catalyzed an unprecedented concentration of decision-making power, and accompanying resources, among elite experts. As computerization advanced, the earnings of workers with four-year college and especially graduate degrees like those in law, medicine and science and engineering, rose steeply. This was a double-edged sword, however: computers automated away the mass expertise of the non-elite workers on whom professionals used to rely.’

As a result, deindustrialised economies, such as the USA and Great Britain, have ended up creating a diploma divide which has then opened up into a diploma chasm. Graduates earn more, they’re also more likely to be employed in the first place, they’re less likely to go to jail, more likely to go to church, more likely to get married, less likely to get divorced and be single-parents, more likely to have friends and an extensive network of people they can rely on for financial and social support, more likely to be connected to social and civic organisations, less likely to be disabled, less likely to experience pain, less likely to commit suicide, less likely to smoke, less likely to be obese, less likely to overdose, less likely to be mentally distressed, more likely to find life meaningful, and they’re more likely to live longer.

Helicopter parenting styles are sometimes presented as being irrational and driven by parental neuroticism but to the extent to which intensive parenting styles are geared towards ensuring children end up on the right side of the diploma divide they are driven by a logical and realistic appreciation of how societies are currently configured.

SCHOOLIFICATION OF CHILDHOOD

However, the trade off is that intensive parenting styles, combined with suburban sprawl and car-culture, have enclosed childhood and led to the demise of what Haidt refers to as a play-based childhood. The term parenting itself—a verb rather than a noun and which implies that being a parent is a form of work—only dates back to 1958 and it wasn't until the 1970’s that its usage soared.

Psychologist Alison Gopnik (in her magisterial book ‘The Gardener and the Carpenter’) reminds us that:- ’the rise of parenting has accompanied the decline of the street, the public playground, the neighbourhood, even recess…Contemporary adolescents often don’t do much of anything beyond going to school. Even the paper route and the babysitting job have largely disappeared.’

This schoolification of childhood, which delays full adult maturity and extends adolescence, results from the extensive requirements of certification in a society that values higher levels of literacy and other skills increasingly located in educational institutions. Journalist Derek Thompson recently reported that in the 21st century, we’ve intensified the demands of the school week and that in many OECD countries, teenagers study longer than the permitted legal working hours for adult employees.

From 1981 to 1997, the amount of time American children up to age twelve spent studying increased by 20%. In that same period, free playtime decreased by 25%, whereas time spent on homework more than doubled. Between 1950 and 2010, the average length of the school year in America increased by five weeks. In the UK school break-times have been curtailed over the years and are as much as an hour shorter than they were two decades ago.

Psychologist Peter Gray has written that ‘Not only has the school day grown longer and less playful, but school has intruded ever more into home and family life. Assigned homework has increased, eating into time that would otherwise be available for play. Parents are now expected to be teachers’ aides…..The school system has directly and indirectly, often unintentionally, fostered an attitude in society that children learn and progress primarily by doing tasks that are directed and evaluated by adults, and that children’s own activities are wasted time.’

The schoolification of children and the intensive parenting styles that have accompanied it are well-intended trends that are designed to ensure that children end up on the right side of the diploma divide but there is plenty of evidence that these trends are also making children miserable too.

School openings are associated with an increased incidence of acute psychiatric emergencies among children and adolescents. Children are less happy in school than in any other setting where they spend significant amounts of time each week. Suicides among 12-to-18-year-old’s are highest during months of the school year and lowest during summer months. Researchers have concluded that youth suicides are closely tied with in-person school attendance. In Britain, suicides among children and young adults peak at the beginning of exam season. Returning from online to in-person schooling in America after the Covid pandemic was associated with a 12-to-18 percent increase in teen suicides. In Japan too, the cyclical pattern of youth suicide is closely related to the school calendar.

EVOLUTIONARY MISMATCH

Human childhood evolved over millennia in a very different environmental milieu than the one which dominates today. Children used to have far more freedom to roam about and to engage in unstructured play and to be active and to spend time in natural environments without constant supervision and surveillance. We forget that mass compulsory schooling is a recent invention and that ‘parenting’ —in the sense of it being a verb rather than a noun —is even more recent. So, at least to some extent, I would argue, that some of the problems of modern-day children and adolescents—which are variously attributed to smartphone and social media use—are, in actual fact, attributable instead to an evolutionary mismatch.

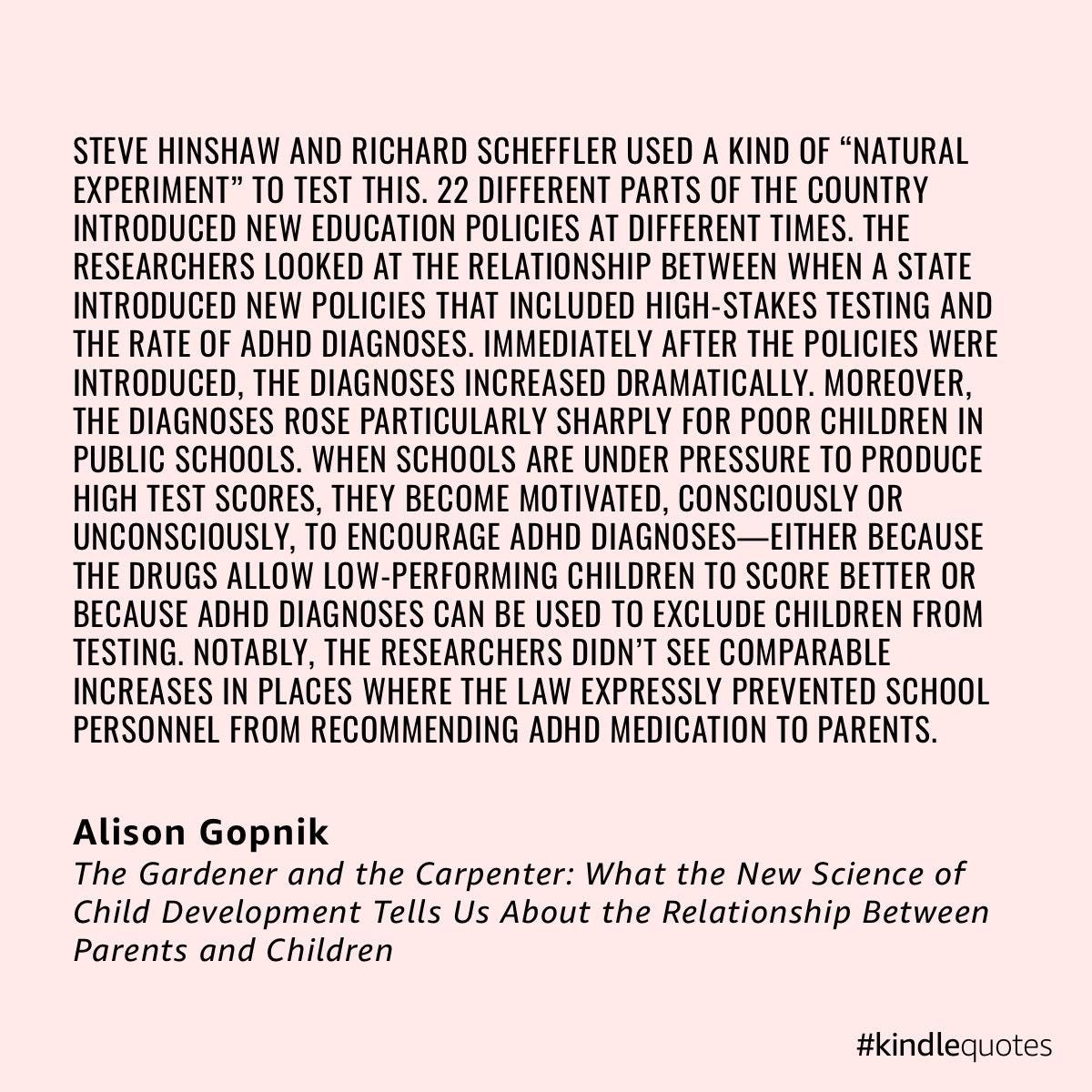

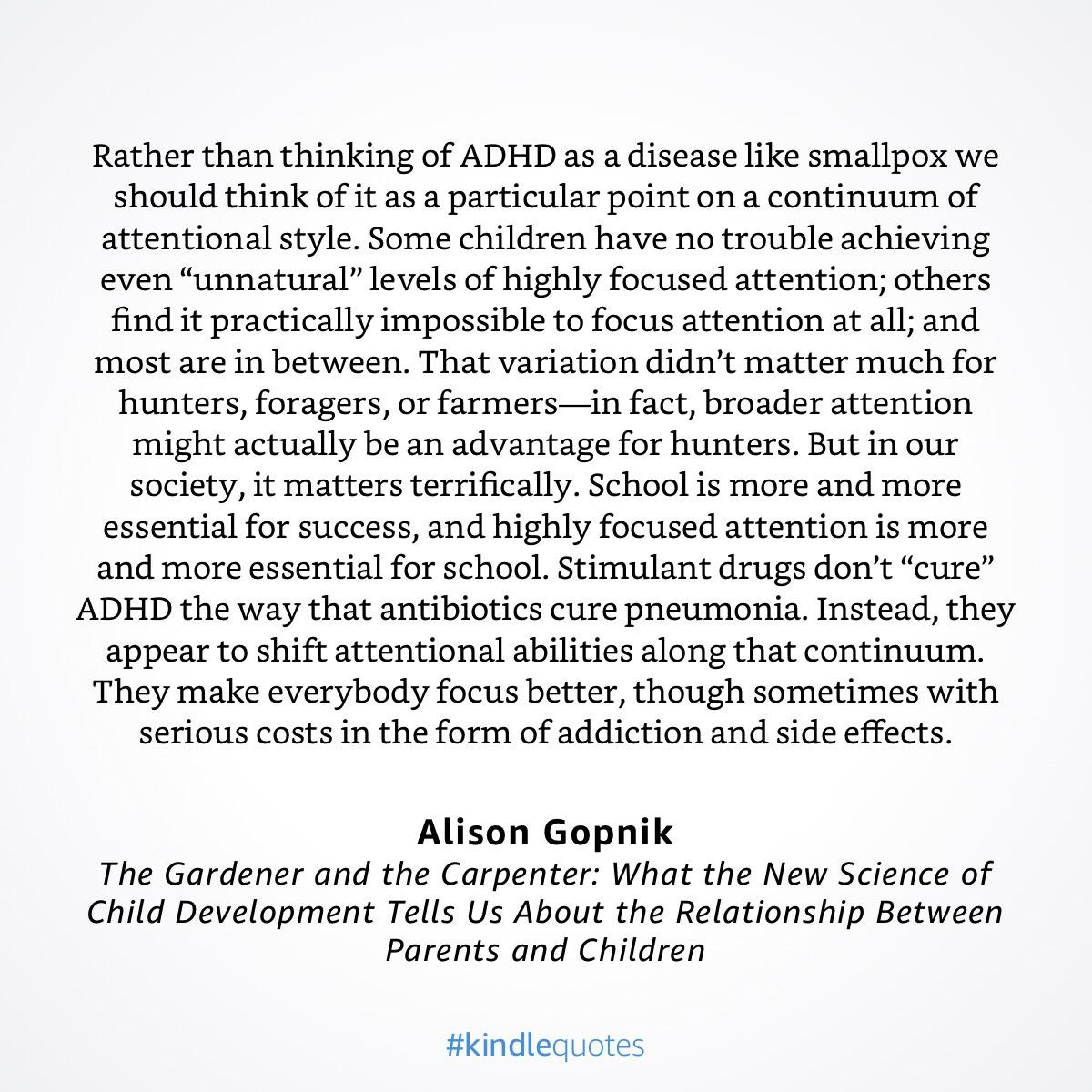

As Alison Gopnik writes (noting the close connection between the rise of schools and the development of ADHD in particular) ‘Children who don’t fit the demands of school are treated as if they were ill or defective or disabled. And this “disease” model is especially prevalent because many of the skills that are most important for school are far removed from the natural abilities and inclinations of most children. In particular, schooling requires the ability to focus attention narrowly. In a classroom, focusing attention on what the teacher says, and just what the teacher says, is essential…The fact that younger and younger children...are not only being diagnosed with ADHD but are also receiving drugs is particularly disturbing. Narrowing attention may be part of growing up, but wide attention is part of being young. It’s not something we need to fix.’

CONCLUSION

The term ‘rewild’ was coined in the 1980s by the American conservationist Dave Foreman and has since helped to popularise efforts to reintroduce wild animals into its old habitats in order to stem and reverse biodiversity loss. The enclosure of childhood resulting from the spread of suburban sprawl, car-culture, intensive parenting styles and the schoolification of childhood has led to the loss of childhood freedom with a corresponding diminished childhood happiness and well-being. If we are to reverse this tide then we will have to think creatively about ways in which we can ‘rewild’ childhood and restore some of their freedom and independence.

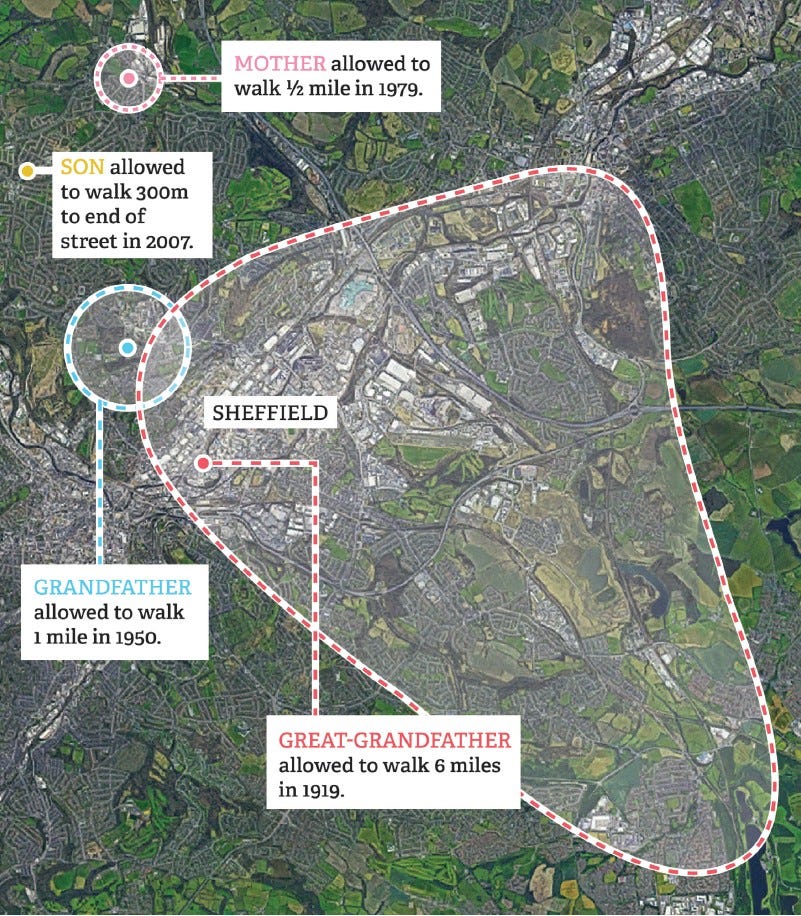

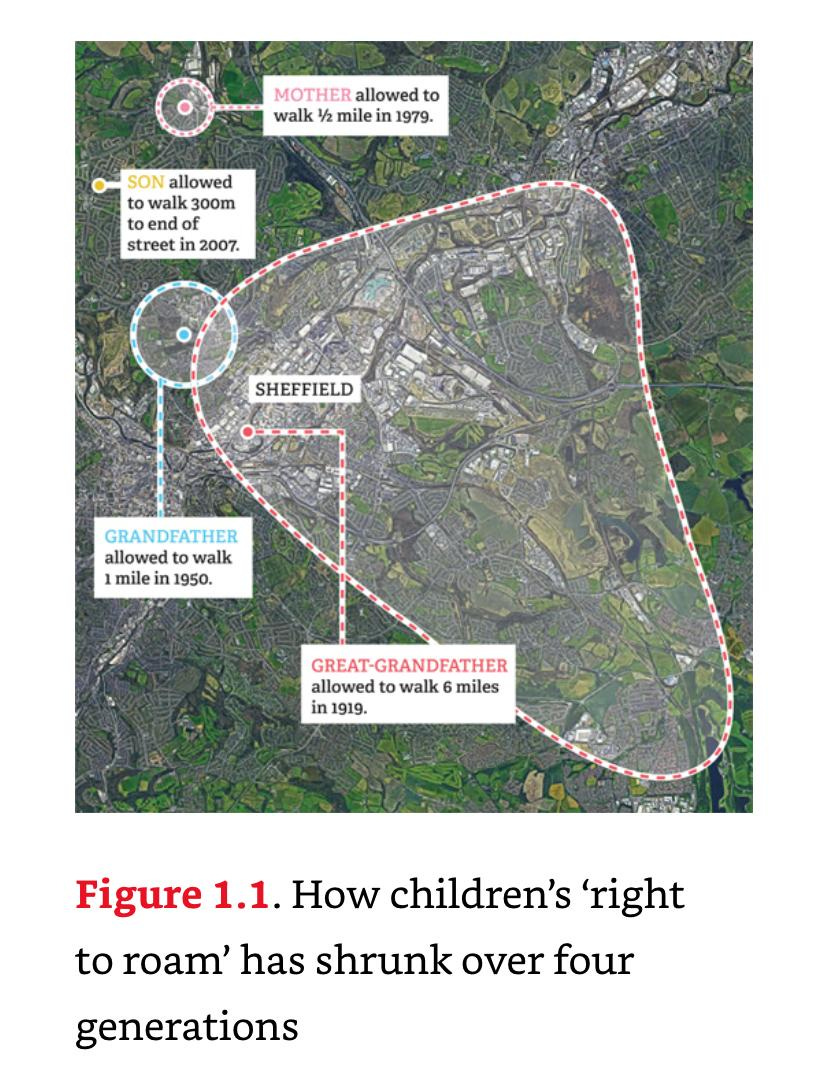

The decline of what Haidt describes as the ‘play-based childhood’ goes hand in hand with a bunch of other trends that pre-date smart-phones. As Hugh Cunningham reminds us:- ‘Children’s mobility outside the home has become seriously restricted. The 'home habitat' of a typical eight year old has shrunk by a factor of nine in one generation…In 1971 eight out of ten seven or eight year olds were allowed to go to school on their own, 20 years later fewer than one in ten. At the age of nine most children in 1971 were allowed to cross roads on their own, to go on non-school journeys on their own and to use buses. In 1990, only half were allowed to cross roads, only one-third to go on non-school journeys and less than one in ten to use buses. The median age at which children were allowed to do these things had risen by two and a half years; what you could do on your own at seven in 1971, you had to wait until you were nine and a half to do in 1990.‘

I agree with Haidt that the decline of a ‘play-based childhood’ is a deleterious trend with potentially baleful consequences but its important to understand that it happened *before* smartphones came along and therefore: taking smartphones away from children will not, in of itself, bring about the return of a ‘play-based childhood.’

What children and adolescents actually need is more access to green-space, more active commuting, more walkability, changed urban designs to facilitate this, more opportunities to engage in free and unstructured outdoor play, less schoolification of childhood, and less intensive parenting. Kids go to school and then come home and do little else. We then wonder why so many of them are miserable. We could take away their screens but that doesnt mean that they are going to go outside, thanks to intensive parenting styles and the schoolification of childhood there isnt the time and thanks to suburban sprawl and car-culture there isn’t the opportunity.

Hi Pete,

I grew up in a rural area, running wild for most of my childhood. I'm mid-fifties now.

I instinctively disagree with you regarding smartphones simply because I have seen what mine has done to me. To paraphrase Jim Carrey from from The Mask, it put my brain in a blender and hit frappé.

I know that's not very scientific, but it's all I've got.

I suppose I would say it's 'both/and' not 'either/or'. You and Haidt are both correct in my opinion.

Regardless, I really appreciate free-thinkers like you challenging my beliefs with such thought-provoking articles as this. I admire that you're so willing to swim against the tide.

I'm a member of a some pressure groups wanting to ban phones from schools and reduce usage amongst kids. I will share your articles on this matter, because you add a lot to the debate and it's good to have our assumptions challenged.

Thanks for your effort putting this together.

I'm convinced by the wilding thesis, but it's hard to see how much will change, at least in the UK. You'd need a government willing to invest in green spaces, discourage car use and tackle urban crime – and these are actually the easiest problems.

Not condemning children who are not suited to academics requires a complete shift in our attitude to economics. And all the decision makers are people who benefited from the current system.