SMARTPHONES HAVE NOT DESTROYED A GENERATION

Tech panic, kids these days and diagnostic inflation

‘If men learn this, it will implant forgetfulness in their souls’ (attributed to Socrates about the new-fangled invention of written text, quoted by Plato in The Phaedrus, circa 370 BC.)

INTRODUCTION

I’ve worked in mental health services for the past twenty years and have watched with increasing frustration as the discourse has coalesced around the simplistic monocausal idea that smartphones and social media are the primary cause of mental ill-health in younger people. My basic contention is that if this were true then it would be reflected in what I have seen in clinical practice over the past twenty years, but this is not what I have seen, nor is it signalled by the noise emanating from extensive clinical research on the matter, which is mixed, to put it mildly. So why has this idea gained such traction? Moreover, who is responsible for promoting this idea? And also, what are the factors that are actually linked to mental ill-health among young people? In this Substack post I will attempt to answer these questions.

THE SMARTPHONE/SOCIAL MEDIA PANIC HAS ROOTS IN THE POPULISM PANIC OF 2016

In 2017 ‘The Atlantic’ published an essay written by the American social psychologist and academic Jean Twenge entitled ‘How Smartphones Destroyed a Generation’. The article —the short form equivalent of her book published in the same year entitled ‘iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood’ —posited the theory that ‘post-Millenials’ (the generational cohort born between 1997-2012 that we now more commonly refer to as Gen Z) were suffering from a mental health crisis caused primarily by smartphones and social media. This was an article that was perfectly calibrated for the time in which it was published, coming one year after the election of Donald Trump as President of the USA and also one year after the Brexit vote, which confirmed the United Kingdom’s decision to leave the European Union, events which were met with widespread shock and disbelief by political progressives on both sides of the Atlantic, and who then reacted by quickly identifying culprits, not least of which were social media and smartphones.

Updating old Marxian ideas about ‘false consciousness’ —-an unfalsifiable idea that Marxists used to explain the lack of enthusiasm for Marxism amongst its intended audience of the industrial proletariat — and combining that with an update of cold war paranoia about foreign governments engaging in attempted mind-control and ‘brainwashing’ of the civilian population, various trans-Atlantic progressives argued that spikes in support for right-wing populist political projects, as exemplified in their mind by support for Brexit and Trump, had resulted from the fact that we were living in an era of ‘post-truth politics’ driven by the ‘filter bubbles’ of the internet, which were then harnessed by nefarious foreign actors, such as the Putinist Russian regime, in order to inveigle the masses into voting against their own economic interests.

For Anglo-American progressives, resurgent right-wing populism was not so much a rejection of their own form of politics as it was a communicable political disease, carried by the air-borne virus of post-truth politics, with the vector of this pathogen identified as the misinformation that had proliferated because of algorithms amplified by social media. Something which, the argument ran, became entrenched in our popular-culture due to the advent of the smartphone. A resurgent right-wing populism wasn't part of an inevitable backlash to policy-decisions made by various neoliberal and progressive politicians, in the 1980’s, 1990’s and 2000’s, to globalise, deindustrialise and liberalise our economies, no, it was all simply Mark Zuckerberg’s fault.

One man clearly taken with these ideas was a social psychologist and academic named Jonathan Haidt who had made a name for himself via the popularity of his 2012 book ‘The Righteous Mind - Why Good People Are Divided by Religion and Politics,’ a book which garnered huge plaudits and subsequently granted him the rarefied status of a bona fide social-science public intellectual, a status which only a handful of academics, such as Robert Putnam and Steven Pinker, can claim to currently occupy. Haidt was clearly aware of the rising wave of right-wing populism back in 2016, given that he had written about the subject for ‘The American Interest’ that year in an article entitled ‘When and Why Nationalism Beats Globalism.’ What is interesting about that article, especially in the light of his later pronouncements on the subject, is the clear lack of concern and curiosity about the potential role of social media in the rise of support for right-wing populism across a number of different countries. By 2019 this had clearly changed as evidenced by his piece in ‘The Atlantic’ published that year with the ominous title of ‘The Dark Psychology of Social Networks’ which made the now familiar and hackneyed argument that social media had facilitated the rise of Donald Trump as a political candidate.

I've written elsewhere about why this idea is false—the common factor underpinning support for right-wing populists are actually ethnocentric backlashes against rising levels of immigration rather than social media use—but the point of this post is not to regurgitate arguments about why support for right-wing populists increased in the 2010’s but to point out that the populism panic of the mid-to-late-2010’s was a rabbit hole that a number of people fell down and which then made the Jean Twenge argument that social media had ‘destroyed a generation’ a plausible one to those people who were already susceptible to this line of argument. Haidt is a notable example of this. Prior to 2016, there isn't much evidence to indicate that he was concerned about smartphones and social media but after 2016 it becomes increasingly evident that it had become a catch-all explanation for a range of different societal problems, including child/adolescent mental ill-health. Given Haidt’s gravitas as a publicly-respected intellectual and his seeming neutrality and objectivity as an ostensible man of science, and a political centrist able to appeal to both left and right, his intellectual imprimatur was a highly consequential development for the spread of these sets of ideas to an even wider audience.

THE MODERN-DAY SMARTPHONE/SOCIAL MEDIA PANIC TAPS INTO THE ANXIETIES OF A NUMBER OF DIFFERENT GROUPS IN SOCIETY

2016 marks a turning point in how smartphones and social media use were perceived. Between 2016 and 2019 there was a sea-change in attitudes towards social media use, exemplified by the intellectual journey of Jonathan Haidt, from a neutral-to-benign view, that it was formerly granted due to its associations with the election of Barack Obama as POTUS in 2008 and the so-called ‘Arab Spring’ of 2011, to the darkly suspicious view which predominates today, in which social media use is blamed by progressives for rises in support for right-wing populism and, in turn, for a number of other societal ills.

If it was only Haidt and Twenge who were convinced by these theories then there would be no point in me writing this blog, however, a number of other groups have also endorsed this form of tech-panic too. Blaming smartphones and social media for a number of societal ills is attractive to a number of people for a number of different reasons. There’s something in it for everyone. Left-wingers blame social media for right-wing populism and right-wingers blame social media for the left-wing ‘great awokening.’ Both sides of the political fence are already inclined to believe the worst about it.

Perhaps most importantly of all, the theme of ‘the next generation is going to hell in a hand-basket and here’s the simple explanation why,’ which the Haidt/Twenge thesis is a modern version of, taps into our natural instinct to care for and to protect our children. It's likely therefore that there will always be a market for variants of this idea and the only thing that will ever change will be the particular locus of that worry and concern. Twenty years ago it was teen pregnancies and video games. Today it's smart-phones and social-media. There is a smaller market for books or articles that tell you that the evidence is mixed about new forms of tech and that the youth of today will probably turn out to be fine. The bigger market is for crystal clear messages that are black and white and prophesying doom.

Gen Z are less likely to engage in a number of problematic and/or worrisome behaviours than previous generations were, but our worry, which stems from our natural instinct to protect our children, will always be there and it doesn't pacify us to learn that children in general are much safer than previous generations were, we will always worry about our own children and that worry will always find an outlet. To paraphrase Samuel Goldman, you could describe this as the law of conservation of moral panic. In any given society, there is a relatively constant and finite supply of parental worry. What varies is how and where it is expressed.

KIDS THESE DAYS EFFECT

{source}

Furthermore, the ‘smartphone/social media is causing all of our problems’ thesis feels intuitively plausible to many people because we are particularly prone to worrying about the social implications of new forms of technology, indeed, anything that is new, and are particularly prone to overestimating media effects in general. The tendency to overestimate the extent to which other people, but not ourselves, are negatively impacted by things like internet misinformation has been dubbed the ‘third person effect’ and is a particularly widespread phenomenon. When applied to the clinical arena, we take it for granted that the mass-media influences clinical outcomes for other people without realising that the evidence for this can sometimes be weaker than many presuppose.

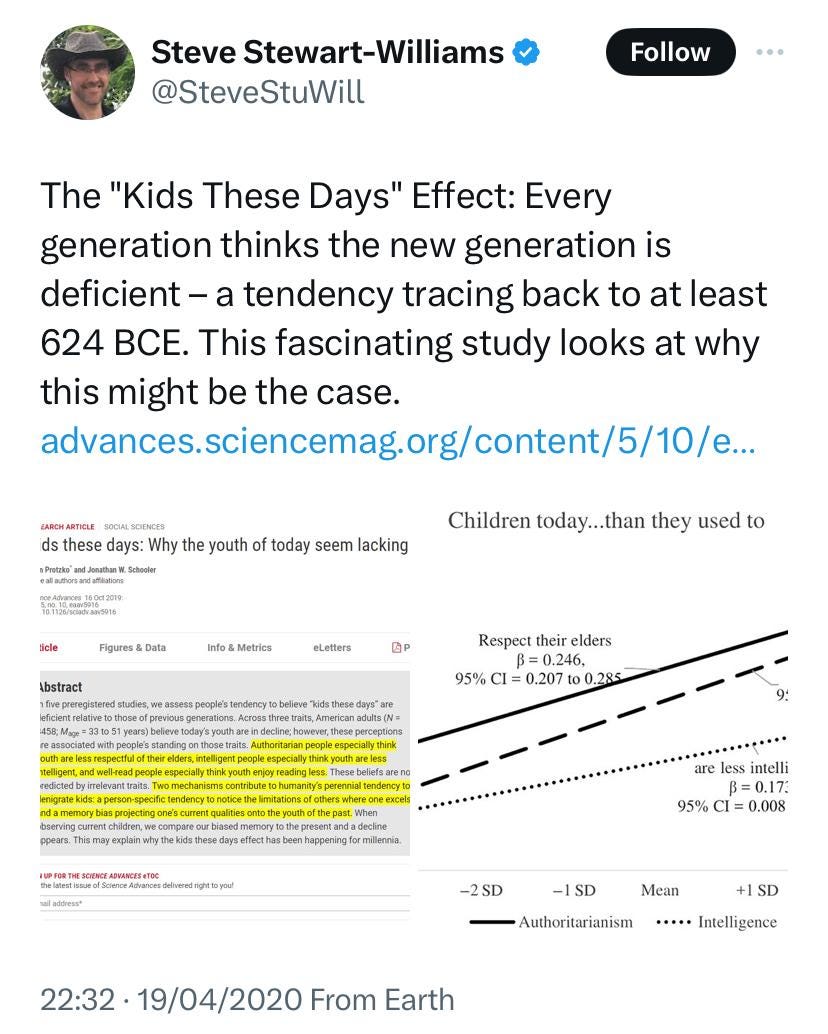

Additionally, you can be sure that with each and every form of technological advancement that emerges (especially when they are popular amongst young people) new moral entrepreneurs will also emerge who seek to make political capital from prophesying doom. This is a modern update of an age-old story that goes back, at least, to Socrates warning about the dangers of writing in ancient Greece and which has been dubbed the ‘kids these days effect’ by John Protzko and Jonathan W. Schooler who write:- ‘The pervasiveness of complaints about “kids these days” across millennia suggests that these criticisms are neither accurate nor due to the idiosyncrasies of a particular culture or time—but rather represent a pervasive illusion of humanity.’

WE ARE POOR FOLK PSYCHOLOGISTS

The Haidt/Twenge thesis takes for granted that there is a global ‘mental health crisis’ amongst young people but we would be wise to treat such hyperbolic claims to further interrogation rather than accepting this uncritically. Unfortunately, such talk fits neatly into many of our existing priors about the world. Not only are we liable to believe the worst about the younger generation anyway but the folk understanding of what constitutes ‘mental health’ and ‘mental illness’ are inherently expansionist. Mental health is routinely conflated with mental wellbeing, perfectionism with OCD, habitual behaviours with addiction, social awkwardness with autism, sadness with depression, worry with anxiety disorders and trauma with PTSD. When confronted by moral entrepreneurs with the imprimatur of social science who claim that there is a global mental health crisis amongst young people that has been caused by smartphones, a message which is then amplified by journalists and politicians, we are already primed to believe them because the boundaries of what constitutes mental disorder in public perceptions has already expanded to such an extent that seems eminently plausible.

THERE IS NO SUBSTITUTE FOR ACTUAL CLINICAL EXPERIENCE

Haidt and Twenge may present themselves (and are treated) as experts on the mental health of young people but they are social psychologists, not clinical psychologists, never mind Psychiatrists, and academics, not practitioners, clinicians or therapists. Nor is mental illness their area of academic expertise either, Haidt is an expert on moral psychology and the focus of Twenge’s research has been in relation to the differences between generational cohorts. Why does this matter? It matters because functional mental illnesses don't have any actual biomarkers, and because of this it is more prone to fads and fashions, and its contours are shaped more by the expectations and values of the culture that it is situated in than is the case in many other areas of medicine. Therefore, there are distinct limits to a purely quantitative approach to the understanding of mental illness. You actually have to see it in the flesh, as it were, to truly understand it, not just read about it in books or research papers. It also means that one should always be slightly suspicious of any reported increases in the prevalence of mental illness until diagnostic inflation has been ruled out first.

Clinical experience is clarifying in two ways. Exposure to the various manifestations of mental illness at close-quarters over a number of years makes it very difficult to take the reasoning of the anti-Psychiatry movement seriously. The anti-Psychiatry movement has many different guises but all forms of it tend to revolve around the idea that because functional mental illnesses do not have any actual biomarkers then this means that mental illness is purely a social construct. It is true that there are no biomarkers for functional mental illnesses but there are no definitive biomarkers for pain either but this doesn't mean therefore that pain is merely a social construct. At the other extreme from the denial of mental illness altogether is the expansionist conception of mental illness which medicalises things which would be better described as social problems, or as problems of living, or as forms of eccentricity or just plain immaturity. Once you have seen the most severe forms of mental disorders then it makes it very plain that those who are high functioning and with mild/transient symptoms don't belong in the same category as the people with the lowest functioning and the highest levels of symptomatology. Twenty years of working in mental health services clarifies that mental illness does exist and it also clarifies what it is and what it isn't.

DIAGNOSTIC INFLATION

The Haidt/Twenge thesis builds upon the expansionist conception of mental disorder, indeed, takes it for granted, but there are a number of good reasons why they should be more sceptical. The reported increases in the prevalence of mental disorders in countries like the UK and the USA have followed increases in both the supply of mental disorders and also the demand for them too. In other words, there have been changes over the last two-to-three decades in how people are diagnosed—the number of purported mental disorders has increased and the thresholds for determining who meets the criteria for a diagnosis of some mental disorders have been lowered in some cases—and also how mental disorders are perceived—well-meaning destigmatisation campaigns have resulted in the overpathologisation of common psychological experiences in some cases—which, it can be argued, has resulted in widespread diagnostic inflation and the normalisation of suicide.

If we change the way that we conceptualise mental and neurodevelopmental disorders, both as professionals and as members of the public, in an expansionist direction, then it should come as no surprise that levels of reported mental and neurodevelopmental disorders will rise even if nothing fundamental has actually changed, other than our collectively tendency to overpathogise. A fact which complicates any analysis of the true prevalence of mental disorders. However, this does not appear to be factored into the Haidt/Twenge thesis at all. It is perhaps in this respect that their lack of clinical experience is most telling.

As American Psychiatrist Allen Frances has written in ‘Saving Normal: An Insider's Revolt Against Out-Of-Control Psychiatric Diagnosis, DSM-5, Big Pharma, and the Medicalization of Ordinary Life’:- ‘Human nature is stable and resilient. There has been no real epidemic of mental illness, just a much looser definition of sickness, making it harder for people to be considered well. The people remain the same; the diagnostic labels have changed and are too elastic. Problems that used to be an expected and tolerated part of life are now diagnosed and treated as mental disorder…if we create an overly broad definition and apply it liberally, we readily recruit an army of new “patients,” many of whom will have been much better left to their own devices. We are not a sicker society in any real sense—even if we see ourselves that way…..Because there are no biological tests or clear definitions that distinguish normal from mental disorder, everything in psychiatric diagnosis depends on very easily influenced subjective judgements. Whenever rates of a mental disorder jump explosively, the safe bet is always on fad. Assume that many, if not most, of the newly identified “patients” are really “normal enough.” They have been mislabeled and will likely be overtreated.’

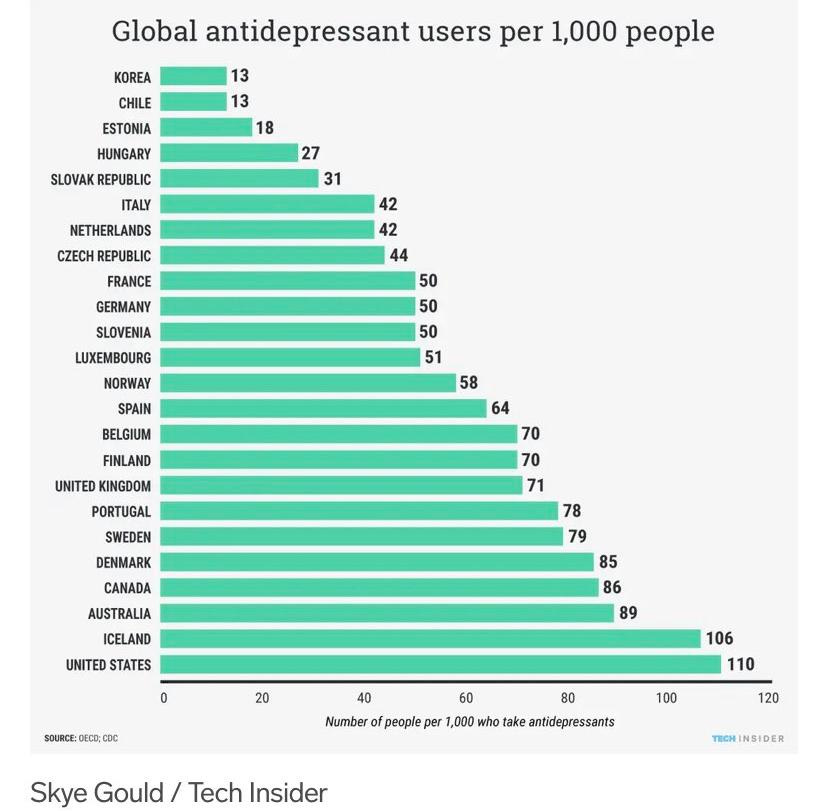

The supply of Psychiatric diagnoses has increased both horizontally —a wider variety of phenomena are now labelled as representing mental disorder with shyness medicalised as ‘social anxiety disorder’ a classic example of what has been described as ‘disease mongering’—and also vertically to encompass less severe phenomena—the huge increase in the number of people who have been prescribed antidepressants in response to milder/transient problems being a pertinent example.

In her book entitled ‘What Mental Illness Really Is… (and what it isn’t)’ British psychologist Lucy Foulkes writes:- ‘When the first edition of the DSM {the diagnostic and statistical manual used by American Psychiatry and which has had a huge influence on world Psychiatry} was published in 1952, it listed 106 disorders, and with each subsequent iteration, that number has grown….there is wide agreement that each time the DSM is updated, the number gets bigger. The first edition had 128 pages; DSM-5 has 947.’ A report by the Centre of Social Justice (CSJ) stated:- ‘Dr Lucy Foulkes…has attributed this rise in mental health diagnosis to a loosening of language where individuals in more hospitable parts of the mental health terrain have started to co-opt terminology that really needs to be reserved for people trapped further in its depths.’

Additionally, the demand for Psychiatric diagnoses has increased exponentially in the face of well-meaning mental health awareness raising campaigns. As Lucy Foulkes puts it:- ‘The lens through which we see our mental distress has been transformed – thanks to the official guidelines and the destigmatising campaigns – so that today we are more inclined to label milder or more transient psychological experiences as being within the realms of a problem or disorder. Not only are people now more willing to talk about previously hidden mental health problems and illness – what people understand ‘mental health problems’ and ‘mental illness’ to be has changed.’

THE REAL-WORLD IMPLICATIONS OF DIAGNOSTIC INFLATION

The real world implications of the expansionist conception of mental disorder are pretty staggering. From the mid-1990s to the mid-2000s, the diagnosis of bipolar affective disorder in children and young people apparently rose by 4,000% in America. In the UK meanwhile, Autism diagnoses have increased by 787% in the last two decades. In America, autism diagnoses quadrupled and now one in every thirty-six 8-year-olds has apparently been given this diagnosis. Since 2020 the ADHD Foundation has reported a 400 per cent increase in adults seeking a diagnosis in the UK. The number of ADHD diagnoses in America increased by 39% between 2003-2016 and now 15% of American 18-year-olds have been diagnosed with ADHD. Among children 2-5 years of age, the rate of diagnosis for ADHD in America increased by more than 50% from 2007-2012. In the UK, a quarter of 17- 19 year olds are said to have a ‘probable mental disorder’ and The Economist magazine has reported that in the UK ‘in 2022 some 57% of university students claimed to have a mental-health issue.’

{source}

In England, between 2000-2019, antipsychotic prescriptions for children and adolescents doubled. In the UK, antidepressant prescriptions for 5-12 year olds increased by 41% between 2015-2021, whilst other studies have shown that antidepressant use in 12-17 year olds more than doubled between 2005-2017, with children in the most deprived quintile being twice as likely to be prescribed antidepressants. Even pre-Covid, 17% of the adult English population were prescribed antidepressants. In Scotland, the figure is even higher, 1 in 4. In the USA, antidepressants are now taken by roughly one in eight adults and adolescents and it is estimated in 2019 that 15.8% of Americans were taking medication for mental health-related reasons, this includes 5% of all children in the USA on medications for ADHD. The increase in the prescription of psychotropic medication is not something we should be taking lightly. Psychiatrist David Healy, in his book ‘Pharmageddon,’ writes that in his estimation ‘drug-induced injuries are now the fourth leading cause of death in hospital settings’ whilst physician and medical researcher Peter Gotzsche has written that prescription drugs are, in his estimation, the third-leading cause of death. If such medications are required (and for some people medication will be required) then that is one thing but if the increase in the prescription of psychotropic medication reflects, at least in part, diagnostic inflation and overmedicalisation, then we risk creating extra levels of iatrogenic harm for negligible benefit.

THE FISCAL IMPLICATIONS OF DIAGNOSTIC INFLATION

The fiscal implications of this expansionary conception of what constitutes mental and neurodevelopmental disorders are also striking. The Times reports that in the UK:- ‘Between 2002 and 2022 there was a 76% in disability payments. One in nine children now has a disability — a rise driven largely by post-pandemic ADHD diagnoses, which represented one fifth of all claims for child disability payments. Last year nearly 140,000 received benefits for behaviour disorders. In 2023, 52,989 adults received disability benefits where ADHD was cited as their main condition, up from 37,784 the previous year, a 40% rise.’ The Resolution Foundation think-tank reports that the number of new personal independence payments claims (PIP) in England and Wales (this is a welfare benefit which was formerly entitled the disability living allowance) is up 138% for 16-17-year-olds, and up 77% for 18-24-year-olds within just the last four years. The Resolution Foundation also report that ‘in 2016, there were just over 8,000 new claims for PIP made by 18-24-year-olds with a psychiatric condition; in 2023 that number is estimated to have almost trebled to 23,000…By 2022, those in their 20s were more likely to classify as disabled with mental health problems than those in their 40s to 60s. Indeed, around one-in-eight people in their late 20s to early 30s now report a disability with a mental health {condition}.’

THE SOCIAL IMPLICATIONS OF DIAGNOSTIC INFLATION

If the increase in levels of economic inactivity amongst the under-25’s in the UK was linked to a true rise in the prevalence of mental and neurodevelopmental disorders then that would be troublesome enough but at least there would be clearly identified clinical pathways to address the situation. However, if this rise in economic inactivity instead represents, at least in part, the result of diagnostic inflation and overmedicalisation then not only are the fiscal implications quite profound but also the social implications too, in terms of wasted potential.

It has more than once crossed my mind that if the current expansionist conceptualisation of what constitutes ‘autism’ had been prevalent when I was growing up in the 1980’s/90’s then I might have been labelled with it given my inherent shyness, social awkwardness and my slightly niche and obsessive intellectual pursuits, but how would it have helped me to label me in such a way? that remains unclear. What did actually help me was working in a person-facing role, which forced me to come out of my shell and talk to people. This allowed me to overcome my shyness and social awkwardness and to eventually fully mature via the adoption of the full-suite of adult responsibilities. Facilitating higher-functioning and non-seriously mentally ill young people to drop out of adult responsibilities and a normal, healthy maturation process by becoming NEETs (not in employment, education or training) is the exact opposite of that.

What some young people need is the opportunity to mature. As young people enter into the rites of adulthood, such as marriage, parenthood and home-ownership, later than previous generations did, then the risk is that immaturity itself becomes medicalised due to a lack of opportunities to pass through the normal adult maturation process. Sadly, there is some evidence to indicate that, at least in some cases, what is essentially immaturity is indeed being recast as disorder.

{source}

THE EVIDENCE TO LINK SCREEN-TIME TO MENTAL ILLNESS IS WEAK

{source}

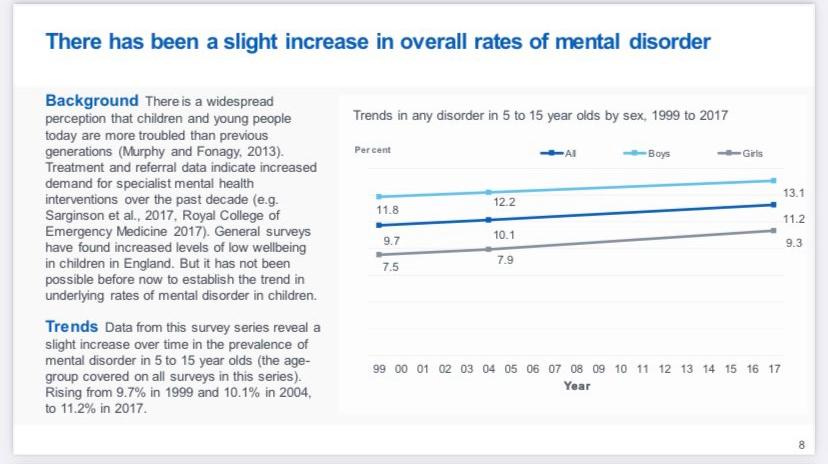

The Haidt/Twenge thesis takes for granted that there has been an international rise in the true prevalence of mental disorders amongst young people which, it is claimed, is of epidemic proportions—something which, as we’ve seen, is, at best, debatable—and that this is linked to smartphone and social media use. If there has been a rise in the prevalence of mental disorders amongst young people then it is likely to be much lower than people like Haidt and Twenge suggest. As The Times reported in an interview with Lucy Foulkes:- ‘Are mental health disorders soaring to “epidemic” levels... they are not... climbing only by tiny amounts. For example, one study found that in 2004 the proportion of 5-15-year-olds with a diagnosable disorder was 10.1%; by 2017 it had risen to 11.2%.’

{source}

If the idea that there is a ‘youth mental health crisis’ is contestable then the idea that social media use causes mental illness is even more contestable. It is noticeable that none of the people pushing the idea that social media use causes mental illness, have clinical experience. This is not an idea that is being pushed by people who actually know what they are talking about when it comes to the subject of mental illness. In the twenty years that I have worked in mental health services and been exposed to people with mood disorders, anxiety disorders, psychotic disorders, personality disorders, organic disorders, in inpatient settings, in outpatient settings, in all age groups, and at all levels of severity, not once have I encountered a case where it was felt that smartphone/social media use was a significant factor in the aetiology of their mental disorder. So either this is a freak coincidence or Haidt and Twenge are wrong.

{source}

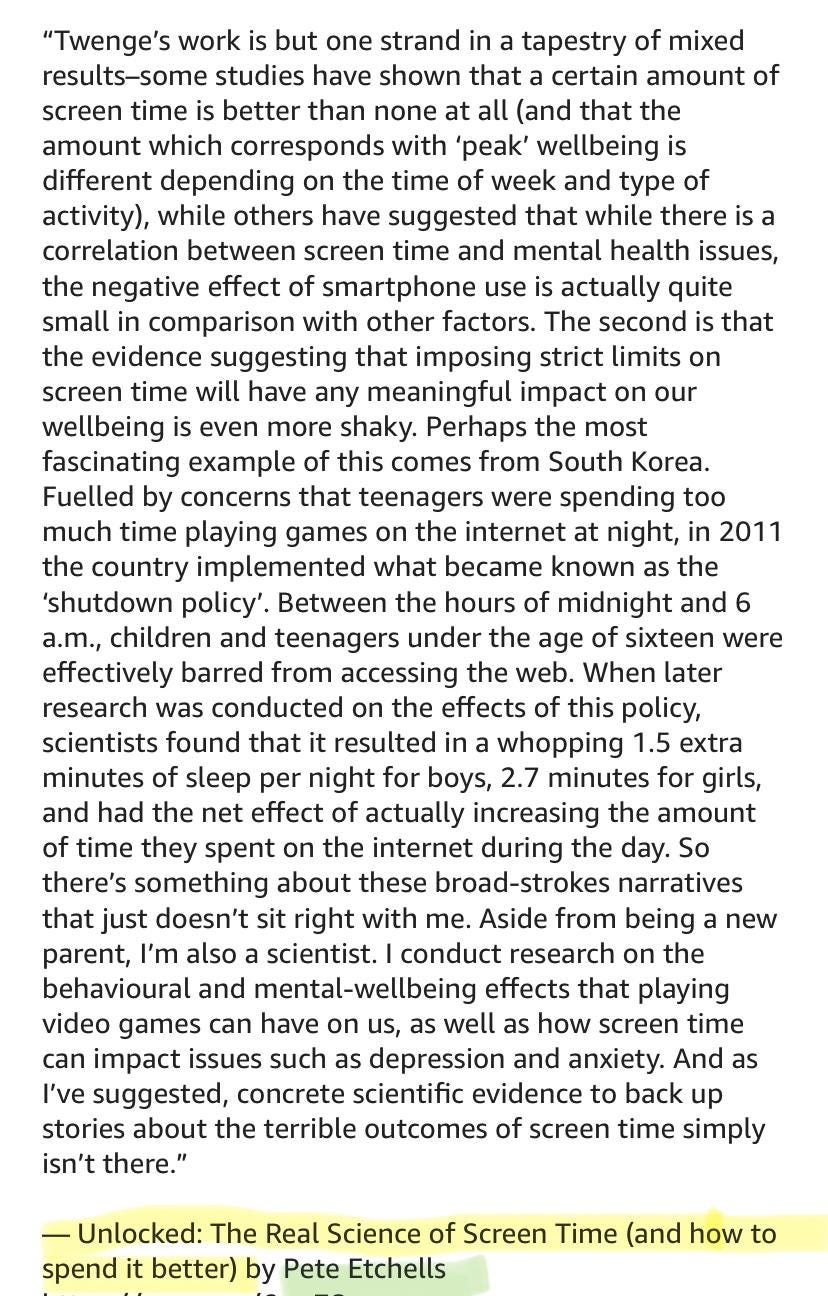

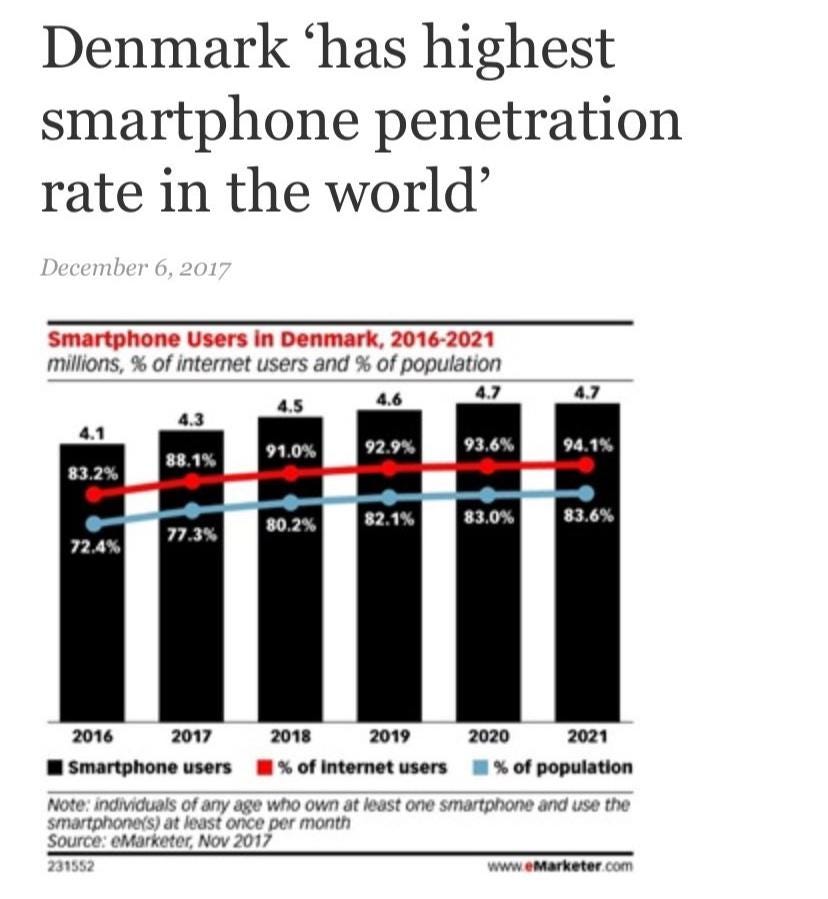

What does the academic research on the matter say? I have tried my best to keep abreast of the research on the topic and compiled as many studies in one place that are relevant to the topic as I could find here. As you can see, there is plenty of academic research to back up my own clinical experience. Smartphone, internet and social media use are global phenemona but increases in teen suicide-rates are not. Dutch children are apparently the happiest children in the world, whilst British children are not, but there is apparently little difference between Dutch children and British children when it comes to their screen-time. Denmark, another country that is regularly near the top of the list when it comes to who the happiest children in the world are, had the highest smartphone penetration rate in the world as recently as 2020, but in the same period saw its teen self-harm rate fall. Whilst an analysis done in 72 countries shows no consistent or measurable associations between well-being and the roll-out of social media globally.

{source}

In his book ‘Unlocked: The Real Science of Screen Time (and how to spend it better)’ psychologist Peter Etchells summarises the current state of the research on the putative links between screen-time and mental illness thusly ‘research which attempts to understand the links between screen time and mental health is so fraught with methodological problems and statistical limitations that we simply don’t have anything near the sort of convincing evidence base necessary to come to firm conclusions about cause and effect. We certainly have nothing to reasonably support the outlandish claim that smartphones have destroyed a generation.’

WHAT FACTORS ARE ASSOCIATED WITH MENTAL ILL-HEALTH AMONG YOUNG PEOPLE?

There are a number of issues linked to mental ill-health in young people but the three main reoccurring ones in clinical practice that you will see most often are adverse childhood experiences, substance abuse and familial dysfunction. I will briefly fly through a non-exhaustive list of other relevant factors that are known to be linked to child/adolescent mental ill-health. Socio-economics status is linked to mental health outcomes. Children raised in families with low socioeconomic status are more likely to exhibit symptoms of psychopathology and are more likely to attempt suicide. Physical ill-health is also associated with an increased risk of mental ill-health in adolescents, just as it is with adults and is associated with an increased risk of suicide. The timing of puberty can also be a contributing factor to some mental health problems, especially among girls, with earlier menarche associated with a higher risk of anxiety and depression. There is some evidence to indicate that hormonal contraception can increase the risk of some mental health problems in young girls too.

Substance abuse is a huge factor to consider when it comes to the subject of adolescent mental ill-health, the most common of which is Cannabis misuse. Cannabis use (especially if it is used more frequently, from a younger age, and the form of the Cannabis being used is more potent,) increases the risk of psychosis, mood disorders, anxiety disorders, self-harm and suicide. Adverse childhood experiences, which range from bereavement to trauma, to abuse, to child maltreatment to bullying are very important factors to consider. Adverse childhood experiences have been found to have strong and dose-responsive association with attempted suicide among adolescents. As regards bullying, which is an oft-mentioned topic when it comes to the issue of social media use among children and adolescents, Lucy Foulkes makes the point in her book that bullying is still overwhelmingly an offline issue, which speaks to the larger point Ive been trying to make in this essay; namely, that it is still children’s offline experience which count the most.

Unsurprisingly, what matters most for young people is still what happens in their offline lives, at home and at school. At school, there is a link between schooling and suicide a finding which has been replicated across a number of different countries. But it is family structure, conflict, dysfunction and breakdown which are, in my clinical experience, by far and away the biggest contributing factors to child/adolescent mental ill-health. Parental divorce during childhood has consistently been linked to increased risk of suicide attempt among offspring. Whilst a large-scale longitudinal study in Sweden found that young boys and girls who were living with single parents were more likely to commit suicide than were youth living with two parents. There is evidence to indicate that there is a higher risk of self-harm and drug-use in children living in lone-parent households and that the prevalence of mental disorders in general tends to be higher in children living in lone-parent households. Father absence is linked to an increased risk of externalising behaviours. Children who experience family breakdown by the age of 18 are more likely to experience mental health problems. There is also evidence to indicate that children with a probable mental disorder are more likely to be living in a family who reported problems with family functioning and that family background is closely linked with children’s mental health problems also. The outcomes for children raised in care illustrate just how important family, and its absence, can be for the mental health of children and adolescents. In England, 45% of ‘looked after children’ were found to have a diagnosable mental health disorder. compared to just 10% in the general population and those with experience of the care system have been found to be four to five times more likely to attempt suicide in adulthood than their peers. Adverse childhood experiences, as we have discussed, are hugely important when it comes to child/adolescent mental health and the child’s family experiences goes a long way to determining their exposure to them, as we can see most clearly in children who have been raised in care.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, the idea that ‘smartphones have destroyed a generation,’ which has been promulgated by Jean Twenge, Jonathan Haidt and others, is the latest instalment of a long running story called ‘the kids these days effect’ and has occurred in the context of a wider tech-panic. Diagnostic inflation complicates any analysis of whether the true prevalence of adolescent mental ill-health has actually increased and the evidence to implicate ‘screen-time’ in child/adolescent mental ill-health isn't strong. There are a number of factors that are associated with the mental ill-health of children and adolescents, and these include substance abuse, adverse childhood experience and familial breakdown, conflict and dysfunction. It remains the case that the thing that matters most for child and adolescent life outcomes is what happens in their offline world, at school, and especially at home. We would be wise not to get distracted by the faddish reductionism of social media determinism and not to lose sight of that fact.

I really enjoyed this piece, thank you! I was particularly interested that you trace the current smartphone/social media panic back to 2016. I'd be tempted to trace its beginnings earlier than that, to the early 2010s, when news outlets began to increasingly publish articles about the "dangerous trends" that were circulating amongst teens on social media like planking and the cinnamon challenge.

Overall I felt that Haidt's book presents a really inaccurate timeline of teen engagement with tech. His own data shows that teen mental health was stable (perhaps improving) throughout the 2000s, the exact decade when teens began compulsively texting (c. 2001), hanging out on MSN after school, and posting photos of themselves to Bebo or Myspace (c. 2005). It was also the decade the first smartphone was released (2007). So an uptick in mental health problems from 2012 doesn't even really correlate with the arrival of smartphones and social media.