THE LOW FERTILITY TRAP

An analysis of the great worldwide baby bust and a critique of pronatalism

The problem of collapsing world-wide birth-rates is a complex topic but I will state my thesis baldly at the beginning: there is a large overlap between the things that underpin long-standing worldwide birth-rate declines and the things that underpin our prosperity. As the biologist John Aitken has put it:- ‘The fundamental cause of human fertility decline is prosperity.’ Therefore, birth-rate declines are hard to undo and reverse because to unpick low-fertility risks also unpicking our prosperity too. Therefore, pronatalists face an uphill battle, to put it mildly. Pronatalism (a term used to describe advocates for policies geared towards increasing fertility rates) is nothing new but has gained greater salience in recent years due to rapidly rising old age dependency ratios across the OECD countries in particular. The Economist reports that the share of countries with pro-natalist policies has grown from 20% in 2005 to 28% in 2019. In any analysis of the merits or demerits of pronatalism it is important to differentiate between liberal and illiberal forms of pronatalism. In its illiberal guise, pronatalism can be motivated by an ugly ethno-nationalist undercurrent which views pronatalism as a means of avoiding what it perceives to be the evils of mass-immigration, which is seen in catastrophic terms as tantamount to ethnic replacement and racial/civilisational suicide. But this form of pronatalism is, at best, a fringe view in this country and I'm not going to waste my time critiquing a set of views which are not held by anyone with any real influence or power.

My critique is aimed at the less sinister and more liberal form of pronatalism which holds sway over a greater swathe of policy-makers. There are bad-faith critics who will try to collapse the two forms of pronatalism into one and pretend that all forms of pronatalism are inherently morally suspect, but this is not a view I subscribe to. My critique of liberal pronatalism is not that it is inherently morally problematic to utilise various policies to try to encourage more people to have children. Pronatalism, in its liberal form, is a perfectly legitimate set of policy aims. My argument is pragmatic, not moralistic. My argument is that liberal pronatalism is simply not going to work. As the authors of Empty Planet’ explain:- ‘the “low-fertility trap” ensures that, once having one or two children becomes the norm, it stays the norm. Couples no longer see having children as a duty they must perform to satisfy their obligation to their families or their god. Rather, they choose to raise a child as an act of personal fulfilment. And they are quickly fulfilled.’

My critique of liberal pronatalism also seeks to avoid falling into the trap of dichotomising economic versus cultural factors, a tendency which tends to obscure, rather than illuminate, analysis of fertility trends. For instance, urbanisation is associated with birth-rate declines (current estimates indicate that 70% of the world’s population will be living in urban locales by 2070 and it's already at 83% in the UK) but is urbanisation a cultural factor or an economic factor? a bit of both is the answer. Economics or culture is therefore a false dichotomy. In predominantly rural societies, children are an extra pair of hands and an insurance policy against old age and sickness when there are no social safety nets, so, in that sense, an economic factor. I once worked with a West African lady (who had been born and raised in a rural location) who described her five children as literally her “pension.” This is a vivid illustration of the ways in which children are viewed as economic assets in predominantly rural societies and stands in stark contrast to urbanised societies, such as the UK, where children are widely viewed primarily in terms of being an economic cost, rather than an extra pair of hands and an insurance against old age and sickness. In industrial and postindustrial societies, complete with extensive social safety nets, and with work located away from home in a factory or in an office, as opposed to at home on a smallholding or a farm, the economic equation of having children is fundamentally altered.

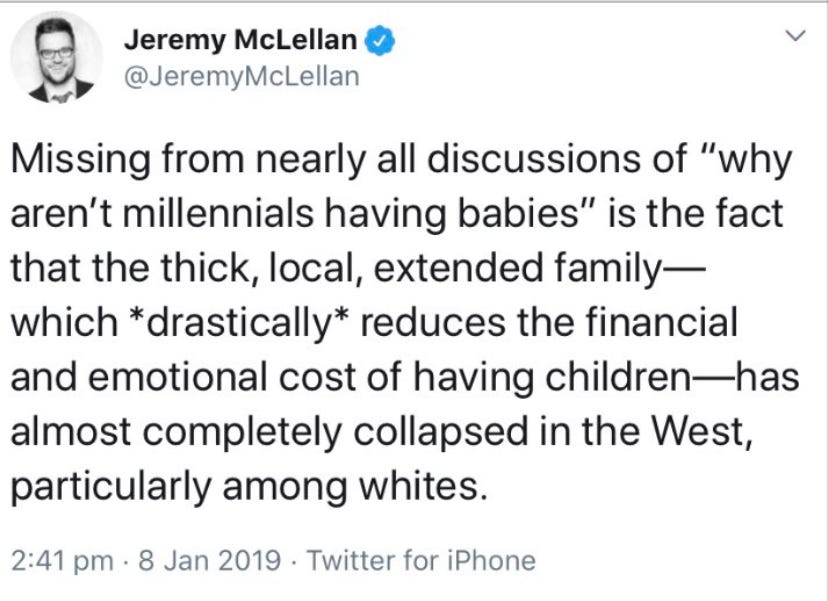

However, cultural factors are also at play. When large families are the social norm within a culture then this has a tendency to become mutually reinforcing. Having a small family, or no children at all, when everyone else around you are having large families, automatically makes you the odd one out. Humans are social creatures with an instinct to conform and this creates a degree of path-dependency with respect to fertility-levels, which can make them difficult to change without a fundamental alteration in material circumstances. Additionally, people in rural societies are more likely to live near an extended family-network. Whereas in urban societies, with its greater degree of geographical mobility, population churn and social dislocation, proximal family networks tend to be replaced with co-workers and university friends and the like. As the authors of ‘Empty Planet’ explain, this has ramifications for fertility because ‘family members encourage each other to have children, whereas non-kin don’t.’

The grandmother effect is a real phenomenon. Research has demonstrated that having a living maternal grandmother increases the number of offspring born by their daughters by about 20% whilst another study found that a grandparental death leads to a reduction of approximately 5 percentage points in the five-year probability of childbirth amongst their offspring. The grandmother effect gives us an insight into some of the cultural factors which underpin higher fertility rates in predominantly rural societies, given that in rural areas people are more likely, on average, to live near extended family and given that there is a positive and statistically significant association of parental support with adult daughters' entry into parenthood. Birth control, as a technological factor, is another good example of the false dichotomy between economics versus culture as regards analysing fertility trends. Birth control measures, such as condoms or the pill, are a material issue, but their take-up is influenced by cultural factors. We can see this quite clearly with respect to the British total fertility rate which fell in 1877 due to a change to social norms when a book about birth control triggered a controversial censorship trial. Birth control is a material factor, but the take up of various forms of birth control are influenced by changes in social norms, which are cultural. Needless to say, economics versus culture, as opposed to economics via culture, is the wrong frame for an analysis of fertility trends.

{Source}

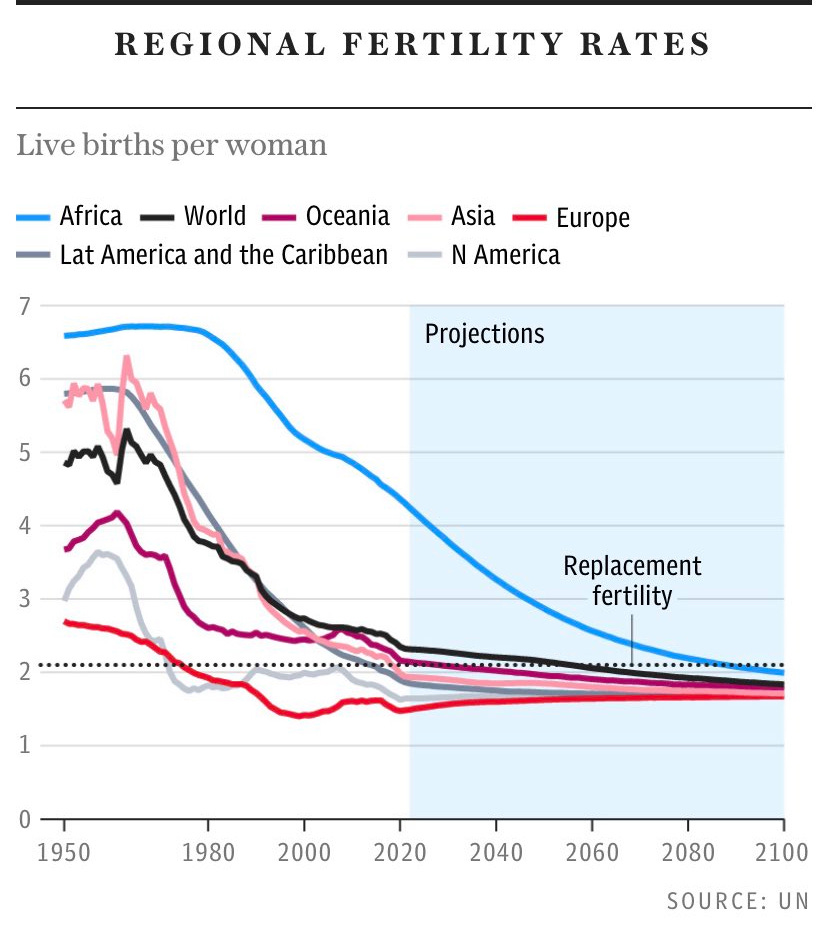

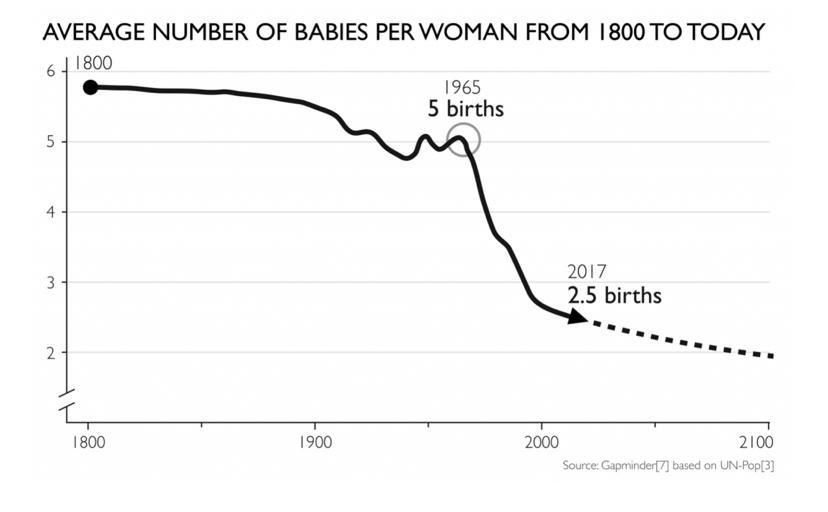

Despite widespread multiple decades-long panic about overpopulation, birth-rates are on the decline across the world. Back in 1800, in all regions of the world, on average, women gave birth to 6 babies each. Even up to 1965 the average woman gave birth to 5 babies. Since then the number has halved. Globally, the average per woman is now below 2.5 children. In the 2015–2020 period, the total fertility rate was 1.61 children per woman in Europe, 1.65 in Eastern Asia, 1.75 in North America, 2.04 in Latin America, 3.25 in Northern Africa, 3.46 in Oceania (excluding New Zealand and Australia), and 4.72 in sub-Saharan Africa. The Financial Times reports that ‘’two-thirds of global citizens live in a country where the fertility rate is less than 2.1 births per woman, roughly the level required for populations to remain stable if mortality rates are low.’ In 1900 children formed 40% of the American population, in 2022, just 22%. Also that year, 61% of US adults lived in a household with a child under age 15, but by 2020 that had fallen to 29%. In Europe, only 29% of households include children, in Sweden that drops below 20%.

{source}

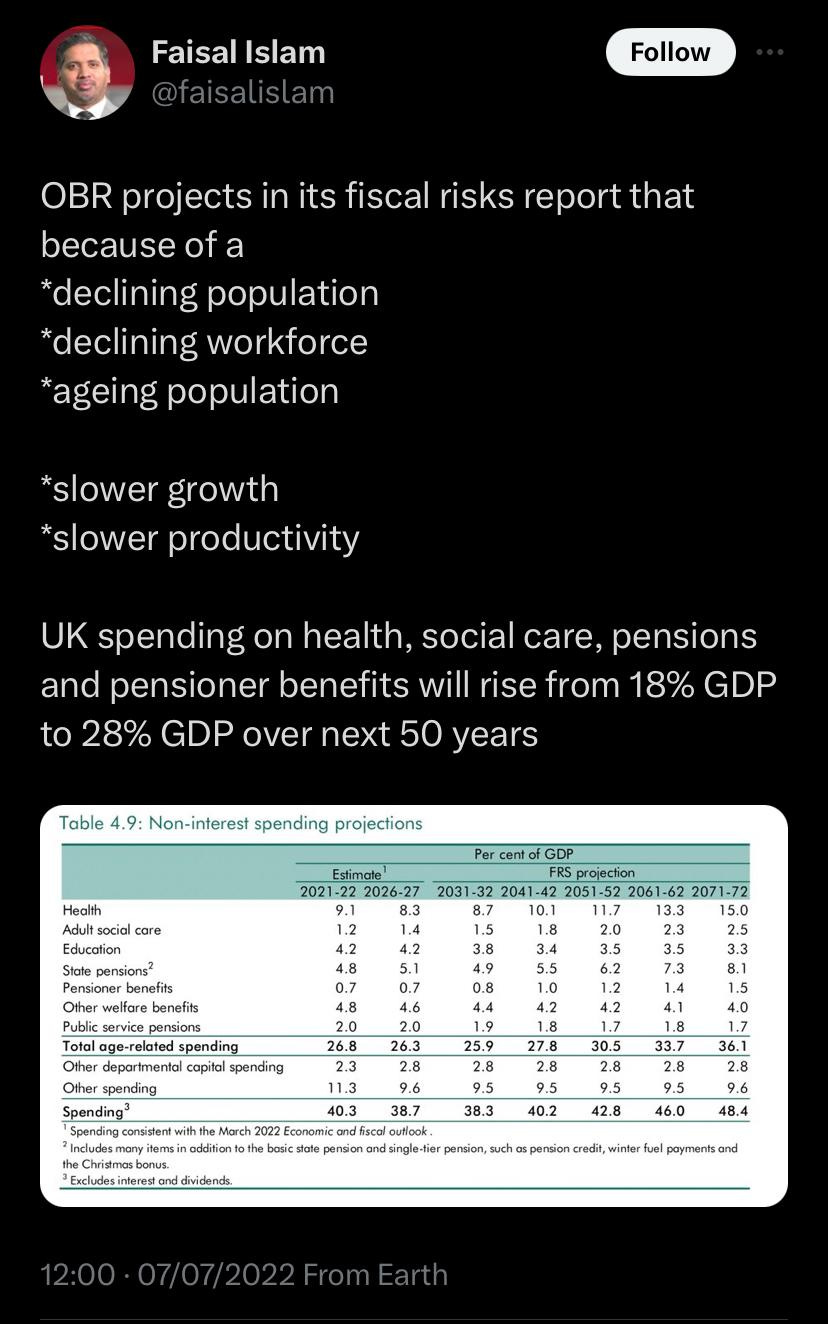

Fertility declines have combined with increases in life expectancy to produce rapidly ageing societies. Scott Galloway has written that ‘globally, the number of people older than 80 is expected to increase sixfold by 2100. Meanwhile, the population of children 5 and younger will get halved.’ The New York Times has reported that ‘in 2020 the median age of developed countries was 42, up from 29 in 1950.’ The Economist reports that ‘the rich world currently has around three people between 20 and 64 years old for every one over 65. By 2050 this ratio will shrink to less than two to one. That will necessitate later retirement ages, higher taxes or both.’ Meanwhile, The Guardian reports that ‘Japan's ageing population is already affecting nearly every aspect of society. More than half of all municipalities are designated as depopulated districts, schools are closing and more than 1.2 million small businesses have owners aged about 70 with no successor.’ Whilst The Times reports that ‘at the moment, there are about 28 pensioners per 100 working people, but this will rise to 39 by 2070. If nothing changes, the Office for Budget Responsibility says that age-related spending will have to rise from 15% of GDP to about 26%.’

A rapidly ageing population has obvious implications for the public finances. The state pension is the largest single item of welfare spending in the UK (£104.86bn in 2021/22) and makes up 42% of the total welfare spend. The Times reports that ‘the cost to the taxpayer of funding university tuition is 8% of the amount spent on state pensions every year (£10 billion compared to £124 billion).’ Whilst the OBR estimates that ‘the ageing of the population, and the associated rise in age-related spending, puts steady upward pressure on public spending and would see public debt more than double to over 250 per cent of GDP by 2070 if no further fiscal action is taken.’ Low fertility has huge implications for public policy in general, as indicated by academic research which estimates that ‘if fertility levels in the UK do not change for the remainder of this century, the nation’s immigration ratio will need to rise to 37% by 2083 to maintain a sufficient working-age population.’ Ageing societies also risk calcifying into gerontocracies with rapidly increasing levels of intergenerational inequality. As an article in The Times put it, ‘a country with fewer children inevitably allocates more resources and more power to older people.’ Whilst CapX reports that in the UK ‘one in four pensioners is a millionaire, whilst the median pensioner….already has more disposable income than the median worker, and is likely to have greater wealth.’

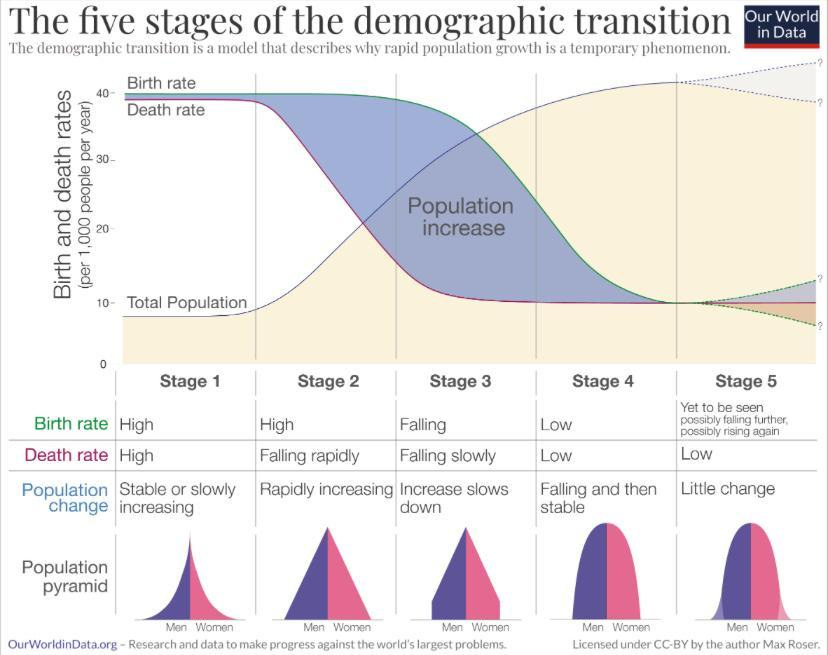

Experts who study demography refer to these combined sets of population changes as the demographic transition. The demographic transition started in North-West Europe around 1800 — the total fertility rate in France, for instance, dropped by 20% between 1800 and 1870 alone —and has been slowly spreading outwards to the rest of the world since then. This demographic transition has been revolutionary in its implications. As demographer Ronald Lee explains:- ‘before the start of the demographic transition, life was short, births were many, growth was slow and the population was young. During the transition, first mortality and then fertility declined, causing population growth rates first to accelerate and then to slow again, moving toward low fertility, long life and an old population. The transition began around 1800 with declining mortality in Europe. It has now spread to all parts of the world and is projected to be completed by 2100. This global demographic transition has brought momentous changes, reshaping the economic and demographic life cycles of individuals and restructuring populations. Since 1800, global population size has already increased by a factor of six and by 2100 will have risen by a factor of ten. There will then be 50 times as many elderly, but only five times as many children; thus, the ratio of elders to children will have risen by a factor of ten. The length of life, which has already more than doubled, will have tripled, while births per woman will have dropped from six to two. In 1800, women spent about 70 percent of their adult years bearing and rearing young children, but that fraction has decreased in many parts of the world to only about 14 percent, due to lower fertility and longer life.’

{source}

Simplified greatly, as country after country have secularised, industrialised, urbanised, and increased its educational levels, birth-rates have fallen (as levels of affluence have risen.) This has huge implications. As the authors of ‘Empty Planet’ put it:- ‘The great defining event of the twenty-first century—one of the great defining events in human history—will occur in three decades, give or take, when the global population starts to decline. Once that decline begins, it will never end. We do not face the challenge of a population bomb but of a population bust, a relentless, generation after generation culling of the human herd. Nothing like this has ever happened before…..Population decline isn’t a good thing or a bad thing. But it is a big thing. A child born today will reach middle age in a world in which conditions and expectations are very different from our own. She will find the planet more urban, with less crime, environmentally healthier but with many more old people. She won’t have trouble finding a job, but she may struggle to make ends meet, as taxes to pay for health care and pensions for all those seniors eat into her salary. There won’t be as many schools, because there won’t be as many children.’

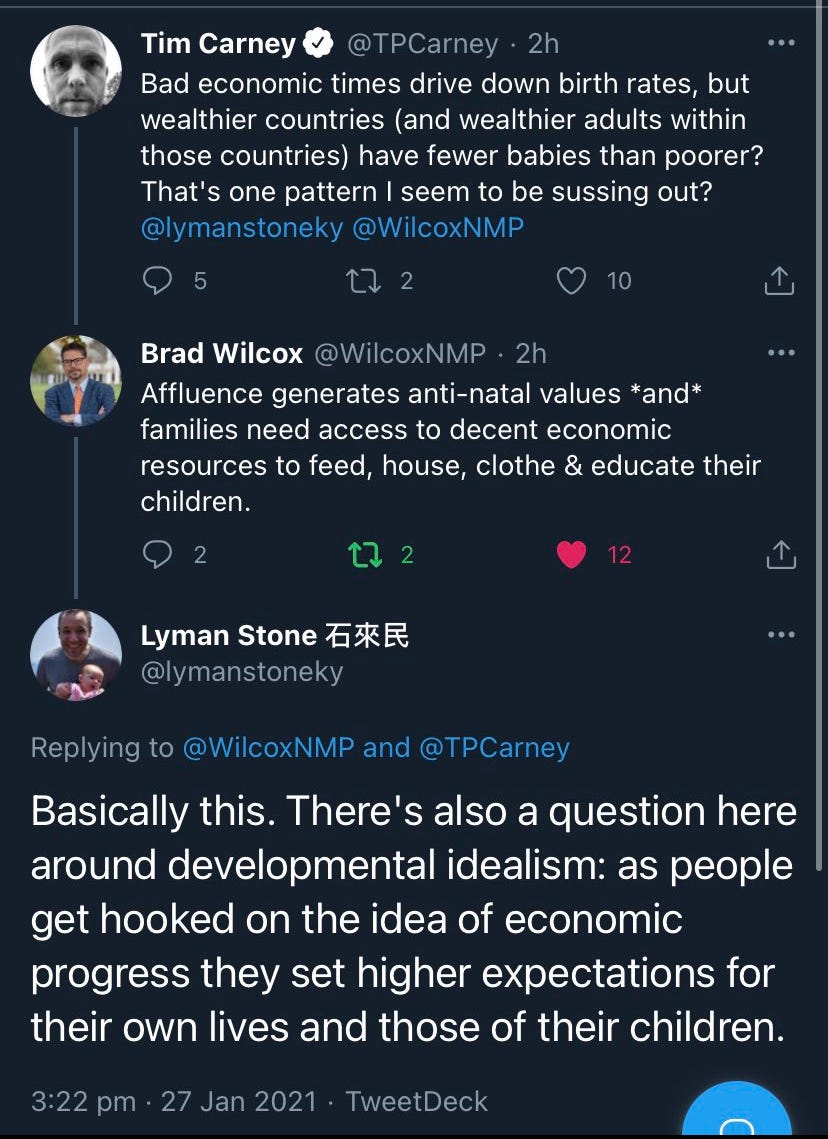

Economic incentives can obviously influence human behaviour but if economic incentives alone explained fertility declines, irrespective of context, then it would be relatively easy to fix the problem, just bung a load of cash at people of child-bearing age and watch the total fertility rate in a given area go up and up, but unfortunately, many countries have tried variants of this approach already with very limited results. Part of the problem here, it seems to me, is that policy-wonk think-tank types are the ones who write about this subject more than anyone else and policy-wonk types are naturally inclined to emphasise aspects of the problem which might be amenable to policy-levers, which tend to be mostly economic, and to downplay things which are less amenable to change via policy, factors that tend to be mostly cultural. We rely on policy-wonks for their specific knowledge about particular subjects but they tend to have their own biases. One of which tends to be the belief that something can be done in regards to the particular problems that form the locus of their area of expertise. A policy-wonk is incentivised to always believe that something can be done with respect to their area of expertise because otherwise: what are they doing exactly? However, sometimes very little can realistically be done with respect to certain intractable problems. In the case of birth-rate declines, if the same factors that play a role in fostering birth-rate declines also play a role in fostering our prosperity then reversing those birth-rate declines will likely involve huge unattractive trade-offs that most people would be unwilling to accept.

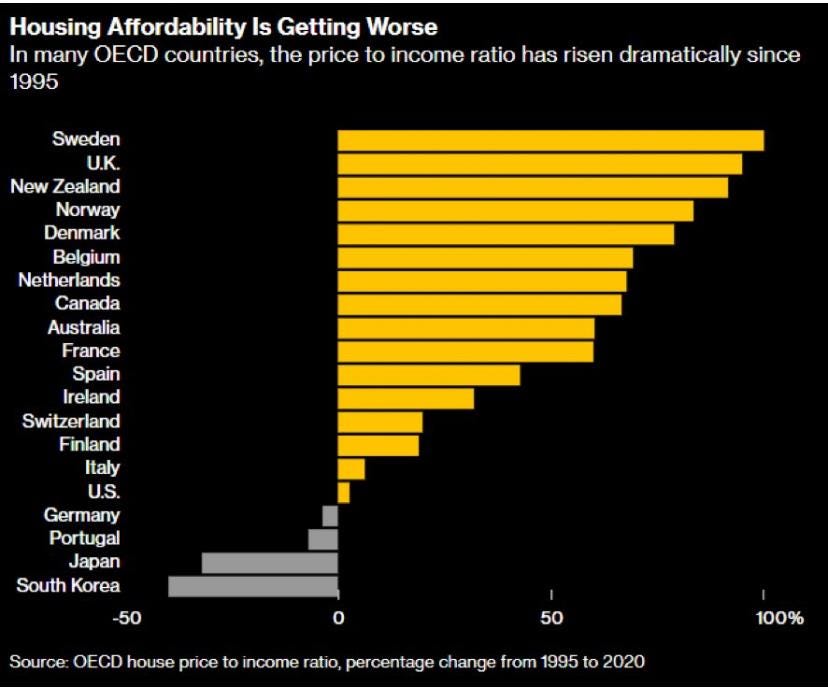

Economic incentives clearly matter when it comes to decisions about having children, but perhaps not in the way some people imagine. There is an unexamined assumption that the primary reason why birth-rates have declined is simply because having children has become more unaffordable to a greater swathe of the population, but total fertility rates were actually a lot higher when we were much poorer and poorer countries, such as those in Africa, have much higher total fertility rates than countries that are far more affluent, such as those in Europe (three times as high in fact.) Clearly there is more to this topic than meets the economists eye. Restrictive planning laws leading to high housing costs, which then preclude young people from becoming home-owners (which is a real problem,) are often adduced as a primary factor behind declining birth rates in this country. This is despite the fact that more houses have been built in Tokyo than in the whole of England since 2008 but yet Tokyo has a total fertility rate of only 1.04, which is not only lower than the rest of Japan but also lower than the rate in the UK too, which currently stands at 1.56 children per woman. The idea that a lack of affordable housing is the primary reason why birth-rates are so low is not a theory which matches the available evidence.

British birth-rates dipped below replacement-rate fertility levels as far as back as the early-1970’s and have stayed below replacement-rate levels ever since then, but our current housing problems, whereby people in their 20’s and 30’s struggle to get on the housing ladder, dates back only to the 1990’s (at the earliest.) Home ownership rates for those aged between 25 and 34 was as high as 51% in 1989 and even as recently as 2011, 43% of the 25-to-34 age group were homeowners, but by 2022, this had reduced to 24%. High housing costs, and low home-ownership rates amongst young people, are a real problem, but they are not the primary reason why the UK has a below replacement-rate fertility level. Low birth-rates predate our current housing problems and the example of Tokyo indicates that building more houses will not, in of itself, do much, if anything, to increase the birth-rate. If increased housing affordability was the simple path to increased fertility-levels then we would expect to see higher fertility levels in countries like Japan and South Korea but that is not what we see.

{source}

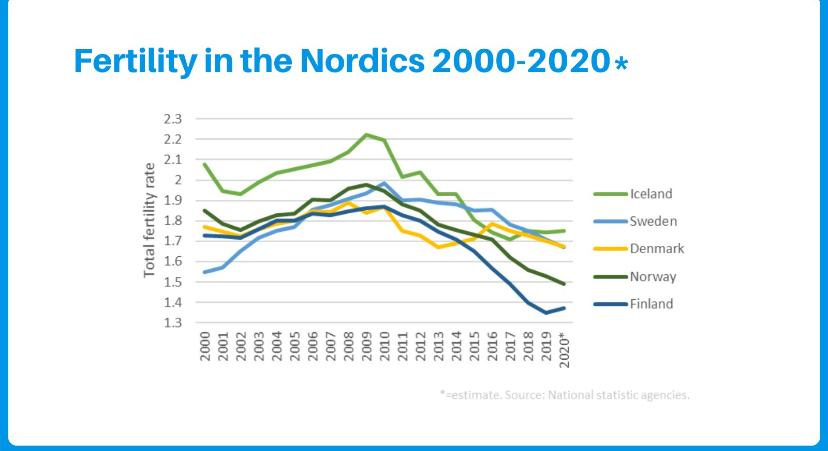

The same applies to childcare. Childcare costs in the UK are exorbitant. The Financial Times estimates that an average dual-earner, two-child family in England, spends about 40% of its disposable income on childcare (as compared to 5% in Germany.) Our childcare system is estimated to be the third most expensive childcare system in the world (behind only Slovakia and Switzerland.) There is no question that this is a serious problem that requires serious solutions but childcare costs are not the primary reason why the UK has a below replacement-rate fertility-level. Our low birth-rate predates our current childcare issues and in countries which have universal free childcare, such as Nordic nations like Finland, we do not see an appreciable increase in the birth-rate. In Norway, for example, the average family only spends 8% on childcare and parents also share 49 weeks of parental leave at full pay, but yet their total fertility rate is also below replacement-rate levels and, as recently as 2020, was lower than the UK rate at 1.48 births per woman compared to 1.56 births per woman in the UK.

{source}

Urbanisation, which generally accompanies industrialisation, creates the conditions for our modern levels of prosperity, via agglomeration effects, but changes the economic equation of having children from one of an economic investment to one of an economic liability. Gradually this leads to less people having children and (combined with increased life-expectancy) results in an ageing society with a reliance on immigration to make up for the shortfall in the workforce. Ageing societies, such as Japan, without high levels of immigration, tend to become economically stagnant and end up racking up huge levels of debt due to a declining number of workers and an increasing number of people who are economically inactive. Whilst ageing societies, such as those in Europe, who have become reliant on immigration to make up for the shortfalls in their working-age population, end up being roiled by nativist backlashes in the form of repeated waves of right-wing populism (which have occurred in country after country following large-scale immigration.)

Tinkering around the edges of the problem with various policy proposals related to tax, housing and childcare, whilst well-meaning, misunderstands the depth and the complexity of the problem. The factors that are associated with high levels of fertility, not just urbanisation, but also religiosity, reductions in child mortality, high marriage rates (plus marrying young) and female educational levels — John Aitken states that ‘the education of women has probably done more to curtail human fertility than the entire plethora of contraceptive technologies and pronatalist Government policies added together’ —are not things that we are likely to reverse, or, in some cases, even, things that we actually want to reverse anyway. So this presents us with an existential societal dilemma. Economic stagnation via low fertility and low immigration, like we see in Japan, or endless right wing populist nativist backlashes via low fertility and high-immigration, like we see in Western Europe and North America. Given that these are the other options, it is unsurprising that liberal pro-natalists cling to the comfort blanket that we can easily shift the dial on fertility by tinkering with policies related to tax, housing, childcare and the like.

Liberal pronatalists cite the fact that people will generally report, when asked, that they want to have more children than they currently have as evidence for the necessity of pronatalist policy-making. However, if you asked the average person whether we should increase taxes to pay for public services then they would also likely say yes but this does not necessarily mean that they want to pay more tax personally themselves. Nobody wants to be obese either and if you asked someone who was overweight or obese whether they wanted to lose weight then they would invariably say yes but that does not necessarily mean that they are willing to make the lifestyle changes that would be necessary to achieve this in an obesogenic environment geared towards sedentary living and with the ubiquitous availability of highly-caloric food. Likewise, in the abstract, people will often say that they want to have more children than they currently have but that does not necessarily mean that they would be personally willing to make the actual trade-offs that would be necessary to facilitate this in an anti-natal environment.

In Vegard Skirbekk’s description of sub-Saharan Africa, in his book ‘Decline and Prosper,’ we get a glimpse into what a high-fertility culture actually looks like:- ‘compared with the rest of the world, sub-Saharan Africa has relatively high levels of illiteracy (34% in 2018) and low education. There are fewer economic opportunities and often restricted access to contraception. People in this world region are generally more religious, tend to have more traditional family values and fatalistic attitudes toward childbearing are widespread. Childbearing and marriage remain close to universal, and majorities marry at a relatively young age. Within marriages, childbearing is often expected and is the basis for legal, social, and cultural systems.’ A high-fertility culture would be one which was less urban, more religious, probably with less birth control, certainly with more teenage births, near universal and early marriages, more unplanned pregnancies, and one in which women started having children much earlier, likely foregoing manifold educational and professional opportunities in the process. In a truly high-fertility culture, there would also likely be less emphasis on the importance of work and education in general too. Some people would welcome a retraditionalised society that was less urban, more religious, and one in which more women had lower levels of education and fewer career opportunities because they were having children much earlier, but many people would most certainly not welcome this set of changes.

{source}

The point being that liberal pronatalists do not even spell this out but offer a misleading narrative instead that we can have everything that we want without having to make any significant trade-offs. Many of the things that liberal pronatalists advocate, such as making home-ownership more widely available, are well worth doing, but they are unlikely, in of themselves, to increase the birth-rate by much, if at all, and certainly not in any sustained fashion. The low-fertility trap that we have found ourselves in goes much deeper than just housing, childcare and tax systems and is rooted in a demographic transition that has come to all societies which have industrialised, urbanised, secularised and increased their educational levels. Urbanisation has given us prosperity but also changes the economic equation of having children from an economic investment to an economic liability. Urbanisation is also associated with changes in social and cultural norms too which serve to mutually reinforce a low-fertility orthodoxy also.

Even the post-second world war baby-boom doesn't offer us a viable road-map out of the low-fertility trap given that it likely happened because young women were denied opportunities in the labour market due to discrimination. If the baby boom was caused, at least in part, by reduced female labour force participation then this is not something that liberal pronatalists would be willing or even able to reverse without the risk of widespread immiseration and political controversy. Immigration does not offer us a viable long-term solution to this problem either given that migrants who move from higher to lower fertility societies tend to adopt the lower fertility patterns of the host country. Immigration maximalism in response to declining birth-rates tends to be unpopular and polarising but so are the other conceivable solutions to the problem of ageing societies and declining working-age populations, whether that be raising pension ages or investing in automation and robotics.

The truth is that there is no simple pat answer to this problem but at the very least we should be honest with ourselves that this problem is not something that we can solve simply by tinkering around the edges with housing, childcare and tax policies. As Norwegian population economist and social scientist Vegard Skirbekk has written:- ‘fertility generally tends to be higher in areas where the population is less educated, where more people are illiterate, and where there is more poverty and fewer economic opportunities.’ If these are the factors associated with high-fertility then most people would happily choose low-fertility. The reality is that the factors which underpin low-birth rate trends are also the factors which are inextricably linked with the prosperity of the countries with low birth-rates and therefore we can't easily unpick one without also risking the unravelling of the other. As Vegard Skirbekk has written, ‘fertility tends to be higher in regions where the population is less educated, more religious, poorer, and more rural.’ This pattern of living is not one which people in the UK are likely to find an attractive option.

{source}

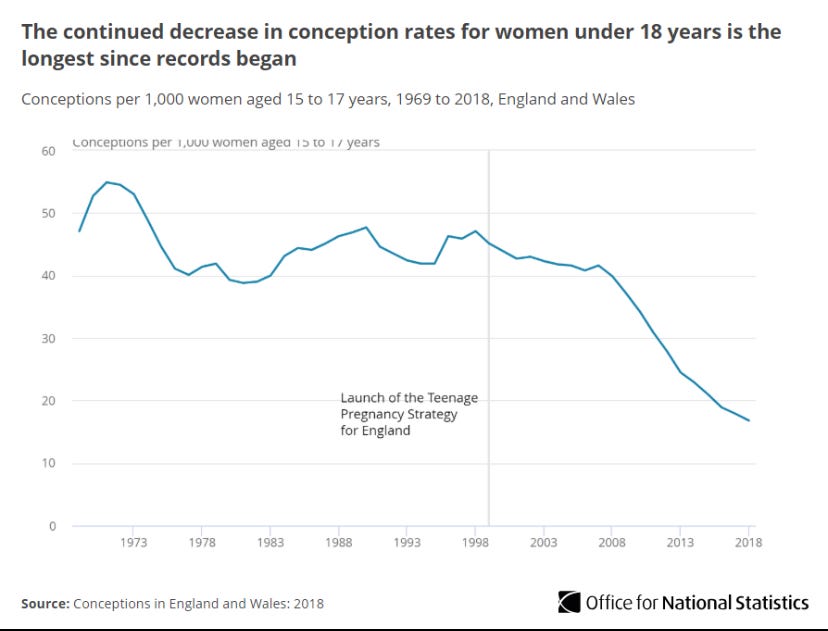

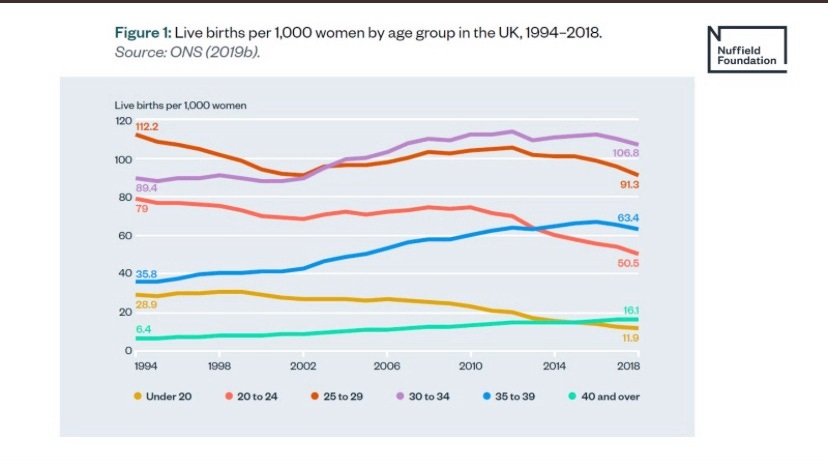

Delayed childbearing is a huge factor underpinning fertility-declines and has become the norm in the UK. The IFS has reported that ‘the average age at becoming a mother has increased by a year per decade since 1970. In 1970 the average age at first birth was 23.7 years, by 2000 it was 26.5 years and in 2019 it stood at 28.9 years.’ Whilst The Guardian reported in 2022 that ‘in 1971, just 18% of 30-year-olds {in England and Wales} had no children – today the figure has risen to 50%.’ Bobby Duffy reports, in his book ‘Generations,’ that in England and Wales in 1985, six times as many babies were born to teenagers as to women aged over 40. But by 2015, the number of children born to women aged over 40 was larger than the number born to those aged under 20, for the first time in our history.’

{source}

This is not an example of British exceptionalism either. Delayed childbearing has increasingly become the norm in industrialised and urbanised countries in general. Vegard Skirbekk writes that ‘given the postponement of childbearing observed in the United States and many other more developed countries, age-related decline in fecundity has become an important driver of modern-day childlessness in industrialised countries.’ This is despite the fact that after the age of 30, women are significantly more likely to miscarry, to give birth to children with congenital diseases and also to remain childless due to declining fecundity. One piece of research estimated that 27 years old is the oldest age a woman should start childbearing for a 90% chance of having 2 children. To reverse the pattern of later childbearing would likely take more than just policy-tinkering with housing, childcare and tax systems however. Reversing the pattern of later childbearing would also likely require some form of retraditionalising of social and cultural norms pertaining to gender roles, birth control, religiosity and marriage, that would not only be beyond the scope of government to socially engineer, but would also, in all likelihood, be highly controversial and unpopular also. We are also not going to de-urbanise either despite the fact that urbanisation is one of the key drivers of low-fertility.

None of this to imply that we should do nothing about falling birth-rates or that falling birth-rates are of no consequence. Falling birth-rates are often analysed in terms of their wider societal ramifications, whether that be in terms of economic or cultural stagnation, but falling birth-rates have deep personal consequences on an individual level too. Falling birth-rates means fewer brothers, sisters and cousins for our children to socialise with and a lonelier world for them in general as they grow older. Rising rates of childlessness are also a worrying trend given that participation in marriage and family life is associated with lower suicide-rates and a longer lifespan. Low fertility rates are also a contributing factor to reduced levels of social trust in general. But we will never be able to address the constellation of issues entangled with low-fertility without a clear-eyed assessment of how we got to this point, and that is something which liberal pronatalism appears to be unwilling or unable to provide. We should also be aware that falling birth-rates have some advantages too. An ageing society is one that is less likely to have violent crime, for instance, given that young men everywhere are responsible for the majority of violent crime. In any case, the low fertility trap is part of a demographic transition that happens to every society which industrialises and urbanises, it's not something that we can eradicate via policy-tinkering nor is it completely negative in every single respect. There are no easy answers to the problems that the low fertility trap poses and we would do well to be sceptical of anyone who proposes otherwise.

Fantastic summation.

Some minor observations:

Given all of the above, with the shift from seeing children from an economic asset to a personal choice (simplifying, I know) men and women have to actually like children. It seems to me that this is absent. Children are often either sentimentalised or seen as a drag on ‘self actualisation’.

Children are perceived as ‘expensive’ - all the paraphernalia that it’s assumed you need for babies, then toddlers - when you need none of it.

The toxification of men, the undermining of the male need to be protectors and providers. Women complaining they can’t find a man with whom they can have children and at the same time demanding that men be more like women.

The rise of dogs as substitute babies - I see that all around me.

It’s literally unsustainable that in order to maintain our current levels of prosperity we have essentially had to transfer a large proportion of the population from having and raising children to wage labour, to the extent the population faces a collapse. Whilst this has produced the most prosperous society in history and has made numerous women’s lives more fulfilling and independent, a declining population traps us in a cycle of ever increasing dependency, which is extremely difficult to pull out of.

Best case scenario, the one that the techno-utopians dream of, and I think most western governments are simply hoping for, is that AI an robotics massively reduce labour demand whilst bio-tech extends healthy working lives into their 70’s. It’s not really a policy, it’s faith in the coming of technological salvation to resolve the problems they are unable to.

One of the most concerning aspects of the demographic crisis is the inability of democracy to enact self correcting mechanisms. Once an older population has established electoral dominance there seems no way to reverse it other than to allow the system to collapse. We’re like a car with the accelerator stuck and the breaks cut. The only way to stop is to slam into a wall. In a similar way, it feels like the only way intergenerational inequality will end is when governments default on their debts and we can no longer pile anymore bills on the next generation and have to start paying for our own care, because no one will vote to make themselves poorer.

If I were to suggests and solution to the problem, i would say that nothing short of making motherhood a paid role would move the dial now but even a modest sum would be hugely expensive and reduce the tax base. Or we could link retirement age to a generations fertility rate, as it really always should have been, because regardless of how much you save, if you have no labour to take over when you retire, you don’t have a feasible retirement plan, other than forcing other people’s children to pay for it or mass migration.

But as I said, no one will vote for these measures, let alone an aging population unwilling to sacrifice their days in the sun, which leaves us back with technological salvation or economic crash as our only options.