THE MYTH OF WENGERBALL

English football has changed beyond all recognition over the last 30 years. Why did this happen, who was responsible and has it been a good or bad thing?

INTRODUCTION

Football, as a game, was codified in the late-19th century but football, as a business, only really took off in the late-20th century, 1992 to be exact. To paraphrase Phillip Larkin: modern football began in 1992 (which was rather early for you) - between the publication of Nick Hornby’s ‘Fever Pitch’ and the introduction of Sky Sports Pay Per View. The story of English football, in particular, prior to the 1990’s, is treated not so much as a history as a prehistory, a veritable dark ages, so the popular narrative runs, until a far-sighted professor from continental Europe ushered in a footballing reformation by nailing his theses to the doors of our establishment and, in the process, saved us from ourselves by getting the likes of the Romford Pele himself, Ray Parlour, and his Arsenal team-mates, to partake of the delights of a Japanese-style diet of steamed fish and veg. If you listened to some people, you would think that before Arsene Wenger arrived in England in the 1990’s that English footballers could barely write their own names and were only able to communicate to each other via a series of grunts. I refer to this simplistic popular narrative as the myth of Wengerball.

WENGER AT ARSENAL

This narrative obscures more than it illuminates but yet has become hegemonic as the dominant popular narrative of the development of English football over the last 30 years. The reality is somewhat different. Arsene Wenger was in charge of Arsenal for 22 years (1996-2018) but won only three league titles and no major European trophies during that time. No one could credibly argue that this was a bad record but it's not exactly era-defining either. Especially when we compare that record to the managerial record of someone like Bob Paisley, for instance, who was in charge of Liverpool for only 9 years (1974-83) but yet managed to win 6 league titles and 4 major European trophies in that time. However, Paisley is only dimly remembered, never mind revered, whereas Wenger, whose achievements, in contrast, were far less impressive, is widely celebrated as a hugely important figure in the recent history of English football.

It is very much arguable as to whether Arsene Wenger was even transformative of the club that he managed, Arsenal, never mind the entirety of English football. In the decade prior to Wenger’s arrival in 1996, Arsenal had already won 2 league titles, 3 domestic cup competitions and a major European trophy. This success was built upon a solid defensive back-line that Wenger had inherited from the man who managed the club from 1986-1995, namely George Graham. This defensive back-line - Seaman, Dixon, Winterburn, Adams plus Bould, Keown and also Ray Parlour in midfield - then became the foundation for Wenger’s first league-title success with Arsenal in 1998. In other words, Arsene Wenger was not exactly starting from scratch when he took over the managerial reins from his predecessor Bruce Rioch in 1996 - who himself had already brought Dennis Bergkamp to the club and who had already changed the style of play too - but was in actual fact taking over one of the most successful teams in the country. If anyone was transformative of Arsenal’s fortunes then surely it was George Graham, not Arsene Wenger. When Graham took over at Arsenal in 1986, they had gone 15 years without winning the league and seven years without winning any trophies. Graham left the club under a cloud due to a financial scandal in 1995, and later managed arch-rivals Spurs, which tarnished his time at the club in the eyes of many of its supporters, but it cannot be denied that he left behind a legacy of sustained success at Highbury not seen since the 1930’s.

Furthermore, not only did Graham revive Arsenal’s fortunes on the pitch but he also played a role in changing the image of the club off the pitch too. Graham was one of the first managers in English footballers to field a sizeable number of black players in his team - such as Michael Thomas, David Rocastle, Paul Davis and, later, Ian Wright and Kevin Campbell. This helped Arsenal to move away from its formerly patrician image and forge a new identity for itself. If Arsenal is now considered to have made ‘a historic contribution to Black sporting iconography’ and if the club has ‘created a special relationship with Black Britain, resulting in a multi-generational Black fanbase’ then this is, in large part, because of George Graham, not despite him.

Arsene Wenger’s real contribution at Arsenal was to build upon the work of his two predecessors - he kept the solid defensive back-line built by George Graham but also continued the work started by Bruce Rioch, who brought in one of the world’s great no.10’s, Dennis Bergkamp, to the club, whilst changing Arsenal’s style of play to a short passing game that suited the Dutchman - and to combine it with his knowledge of the market for the best young players in French football. This was at a time when, compared to today at least, foreign players in the English top-flight were few and far between, and at a time when the French national youth academy, Clairefontaine, established in 1988, was first starting to to bear fruit by churning out some of the best young players in the world.

Clairefontaine is now world-renowned for its development of young players, drawn predominantly from the Banlieues of the Île-de-France region, but back in 1996, its huge potential was less well known outside of France. Having a manager with unrivalled knowledge of the French market for young players gave Arsenal, at that time, a distinct advantage over its rival English competitors. Wenger brought in a number of young French midfielders and forward players (as well as some older French players like Manu Petit and Robert Pires,) and then combined them with the existing English defence built by George Graham and the Rioch-bought Dennis Bergkamp. The addition of the French central-midfielder Patrick Vieira, in particular, proved to be especially important. In the 9 seasons that he was at Arsenal, they finished in the top-2 in the League on 8 occasions. In the 23 seasons prior to that? just twice, in the 18 seasons after that? only twice again. It's a testament to how important Vieira was to Arsenal that it’s taken 18 years to properly replace him, a full 5 years after Wenger finally left the club.

In summary, the building blocks for success at Arsenal were already in place long before Wenger arrived, indeed the club was already one of the most successful clubs in the country when he arrived, only Liverpool had won more English League-titles than Arsenal when he arrived in 1996. It has to be acknowledged though that Wenger did use his knowledge of the French market to add a certain va-va-voom to the Arsenal side but this competitive advantage lasted only until the mid-2000s. The second half of the first decade of this century saw a decline in Arsenal’s fortunes as the rest of League caught up by casting its net even wider than Clairefontaine for the best of global footballing talent. In his last 13 seasons at the club, Arsenal managed a top-2 finish in the League only once, in the 2015/16 season, when they finished ten points behind first-placed Leicester.

Wenger at Arsenal was evolutionary, not revolutionary, and his time at the club was not so much a big bang as a high-class engine that was kept purring along, for a period of time, in the hands of a capable driver before being caught up and overtaken by a number of younger drivers going at greater speeds. Good, very good even, but not exactly an all-time great of the English game. Ultimately, no manager at one of the biggest clubs in one of the major European leagues can credibly be classed as an all-time great if they have never won a single European trophy. So why is it that Arsene Wenger is remembered as being such a singularly transformative figure, not just in the history of Arsenal football club but also, even more implausibly, in regards to the history of English football more generally? Why has his role in the recent history of English football been exaggerated out of all proportion to his actual achievements? To answer this question it is necessary to put English football into some kind of wider context in the early 1990’s. Put simply, English football at the start of the 1990’s had a serious image problem.

THE STATE OF ENGLISH FOOTBALL IN THE 1980’s

English football, at the start of the 1990’s, in the words of an infamous Sunday Times newspaper article from 1985, had become viewed as ‘a slum sport played in slum stadiums increasingly watched by slum people.’ The latter half of the 1980’s, in particular, was an unmitigated disaster for the reputation of English football. The 1980’s ended with the Hillsborough disaster in which 97 Liverpool fans died following a crush at the 1989 FA Cup semi-final between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest. Earlier that decade, in 1985, there was a full-scale riot before, during and after the FA Cup quarter-final, between Luton and Millwall, in March of 1985, which injured 47 people. In the same year the Bradford City stadium fire disaster occurred in early May 1985, which killed 56 spectators. Later that same month, there was the Heysel stadium disaster in Belgium, in which 39 people died, before the start of the European Cup final between Liverpool and Juventus. The decrepitude of the stadium, and the ineptitude of the organisation of the event by the authorities in charge of the game, each played a role in this disaster but the role played by Liverpool fans, in regards to the largely Italian death-toll, cannot be denied also.

Violence amongst spectators at competitive sporting events is at least as old as the Nika riots, which date back to the 6th AD, but football hooliganism in the 1980’s, rightly or wrongly (other European countries did have hooliganism problems of their own in the 1980s lest we forget,) was viewed as a particularly English malaise. Indeed, it was literally dubbed the ‘English disease’ by some. The English were not the only ones engaged in football hooliganism but their reputation for hooliganism wasn't unearned either. Leeds United were banned for four seasons after crowd disorder at the 1975 European Cup final and Manchester United were expelled from the European Cup Winners Cup after crowd disturbances in a game against French side Saint-Etienne in 1977. The Heysel disaster was the last straw however for the European governing body, UEFA, who (more or less immediately after Heysel) excluded all English clubs from European competitions for the next 5 seasons and, in Liverpool’s case, for the next six seasons.

This had a devastating impact on English football and compounded its multiplicity of existing problems. Some clubs have never really fully recovered. Everton, who were due to play in the European Cup in the 1985/86 season and who would have been one of the favourites to win the competition that year, lost their manager (Howard Kendall) and best player (Gary Lineker) to Spanish football, plus a number of other players to Scottish football, as rival countries took full advantage of English football’s misfortune, during the ensuing wilderness years. Everton then went on a gradual slide from being the second most successful club in the country (which they were in the late-1980’s in terms of number of League-titles) to the club that exists today, lost in a seemingly never-ending series of relegation-haunted quagmires.

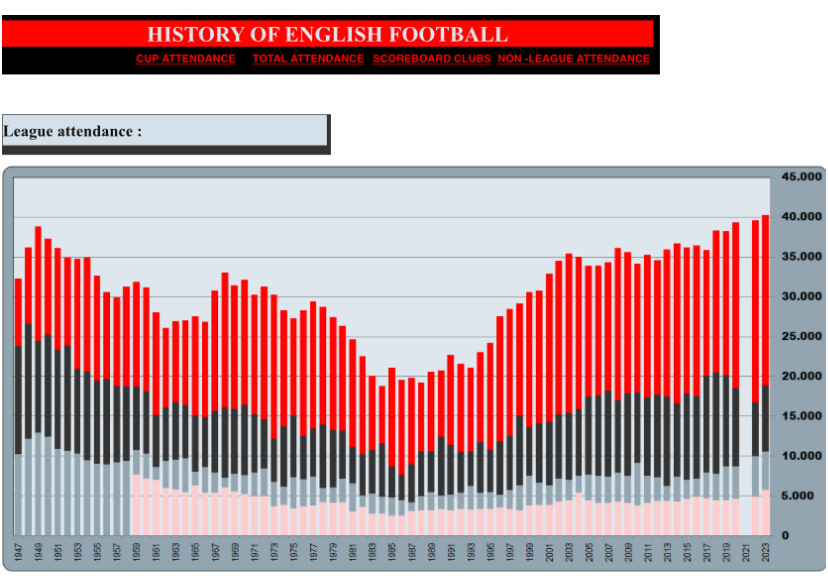

Average attendances to football matches in the English top-flight cratered during the 1980’s and by the 1985/86 season crowds had fallen to their lowest since 1922. The quality of the football on the field dropped too. Cut off and isolated from the cross-fertilisation of footballing cultures that competitive European football can provide, and absent the stimulus to learn and adapt, both tactically and technically, English football started to become an extreme example of the worst version of itself. This was typified in the form of Wimbledon football club, who had been a non-league club for its entire history up until 1977, but who then catapulted their way to the old English 1st division by 1986. Wimbledon finished 6th in their first season in the top-flight in 1986/87, and then, most famously of all, won the 1988 FA Cup. 1980’s Wimbledon represented a peculiarly English form of anti-football that combined route-one football and outright thuggery in order to maximise what little they had in terms of financial resources and footballing ability. Anti-football was nothing new, it was essentially what Alf Ramsey was complaining about when his England side faced an aggressive Argentinian national side in the 1966 World Cup Quarter-Final and also what Brian Clough was complaining about in regards to the notoriously pugnacious Leeds United side of the 1970’s. The difference being however that the Argentinian and Leeds United sides of the 1960’s and 1970’s could actually out-play their opposition, as well as out-fight them, whereas this was not the case for the Wimbledon side of the 1980’s. No one can blame Wimbledon for making the most of what little they had but it speaks volumes for the quality of English football at this time that it was as successful as it was.

If stadium disasters, hooliganism, European bans and reduced attendances were not enough to cast a pall of gloom over the entirety of English football then, to top it all off, as the 1990’s began, Graham Taylor became manager of the English national side. Taylor was basically Tony Pulis avant la lettre, a man who had established his managerial reputation with sides who played direct, route-one football. Taylor was a disaster as England manager and completely out of his depth, with his time in the job culminating in the failed attempt to qualify for the 1994 World Cup. England had twice failed to qualify for the World Cup in the 1970’s but English football at least had the success of its clubs in European competitions to salvage some pride, whereas in 1993, when Taylor stepped down as England manager, there was nothing else to fall back upon and the ignominy of this failure created an indelible impression in the public mind that English football had taken a wrong turn.

There are a number of different factors which explain the decline in popularity of long-ball football in England including the decline in tackling, which has accompanied various rule-changes, allowing creative players who are comfortable on the ball more freedom to dictate the tempo of a game, plus the success of Spanish football, which has helped to popularise a form of football dubbed ‘tiki-taka’ and which places greater emphasis on retention of the ball during play. In his book about the evolution of tactical developments in the English Premier League over the last 30 years, Michael Cox emphasises the introduction of the back-pass rule in 1992, which prohibited goalkeepers from picking the ball up when it was passed back to them by an out-field player, as being one such factor, due to the fact that it necessitated goalkeepers and defenders becoming much more comfortable on the ball. However, Graham Taylor’s embarrassing failure as England manager is also an under-rated factor.

Long-ball football in England was probably shaped by such factors as the weather, the rain-sodden pitches which were once common in English football and were not conducive to a passing game, plus the crowds who demanded excitement on a Saturday after working all week in monotonous work-place settings such as factories and the like. Football is a bit like quantum physics in that the observer plays a role in shaping what he is seeing and in English football during the industrial-era, crowds wanted full-throttle aggression and no-nonsense tackling. English football, as a consequence, has tended to produce more David Batty’s than Michael Carrick’s. In post-war England, however, this style of football was also shaped by such figures as Charles Reep and Charles Hughes who wielded a great degree of influence and helped to provide a respectable sheen of mathematical rationality to this form of football. Data-analysis in football is now associated with forms of football in which the ball is kept predominantly on the floor and play that is built out from the back but in a previous era of footballing data-analysis, men like Hughes and Reep used it to justify long-ball football. In the period from the 1950’s to the 1980’s therefore, long-ball football could be rationalised as representing the forces of modernisation but by the 1990’s this viewpoint had been thoroughly discredited and it now became associated with all the forms of footballing backwardness which we sought to eschew. We have Graham Taylor’s failure as England manager, in part, to thank for this change in perceptions.

This is the context for Arsene Wenger’s arrival into English football in the mid-to-late 1990’s. He arrived at the perfect time for an outsider to come into English football and make an impression. English football had hit complete rock-bottom, both on and off the pitch, in the late-1980’s/early-1990’s, but by the mid-1990’s, when Wenger arrived, the diminution of crowd-trouble following the Taylor report (and the introduction of all-seater stadiums,) plus the injection of new monies (thanks to the Sky Sports TV deal,) not to mention the newfound buoyancy and optimism which now pervaded English football at this time (created by the successfully hosted Euro 96 tournament,) provided an atmosphere that was conducive to change.

THE COMMERCIALISATION OF ENGLISH FOOTBALL

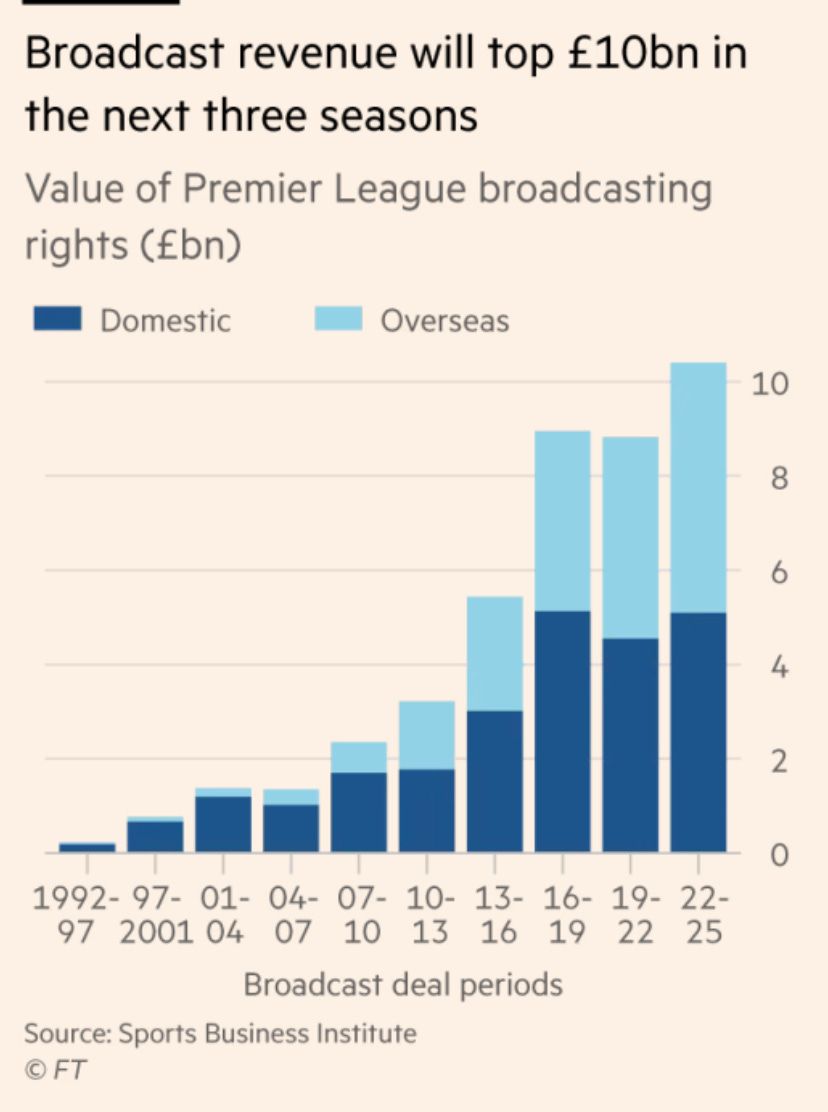

English domestic football has subsequently changed dramatically over the last 30 years to the point where it has now become ‘one of the country’s most valuable products and biggest exports, reportedly reaching 900 million people around the world — more than 13 times the population of the UK.’ In the 2019/20 season alone the English Premier League is estimated to have contributed £7.6 billion to the UK economy and it has become a key aspect of British soft power, akin to British pop music or the Harry Potter books, i.e a recognisably British cultural product that is popular on a global level. As Janan Ganesh put it ‘The French statesman Mirabeau is meant to have said that Prussia was not a state with an army, but an army with a state. England, from outside, can seem like a football league with a nation. It has a claim to be our number-one soft-power asset. The “EPL” is the subject a stranger is likeliest to raise with me upon hearing my accent in the US (where “Premier” rhymes with “Vermeer”). I’ve seen a bar showing West Ham at 2am somewhere around Sukhumvit Soi 12 in Bangkok. No great shock, until I tell you that it was a repeat from the 1993-94 season.’

Simply in terms of revenue, English football clubs now make up 11 of the top 20 in the world. The plans for a breakaway European Super League may lie torn and tattered on the floors of boardrooms, in such places as Turin and Madrid, but, in one sense, such a League already exists, the English Premier League, in a financial sense, is the Super League already. The Premier League’s bottom club receives more TV income than every club in continental Europe except Real Madrid, Atlético Madrid and Barcelona.’ The huge revenue generated by English top-flight clubs means that they are in a position to hugely out-spend their competitors in the rival European leagues, a competitive advantage which is now starting to show on the pitch. Two of the three major European trophies in the 2022/23 season were won by English clubs and three of the last five winners of European club football’s flagship competition, the UEFA Champions League, have been won by three different English clubs too, twice in all-English finals. Attendances are buoyant, England’s second-tier, is the third best attended league in Europe and the bad, old days of English football hooliganism seem like a long time ago. If anything, English football now has the opposite problem, i.e a lack of atmosphere. Roy Keane’s complaints about a ‘prawn sandwich brigade’ have only grown more relevant over time, but gentrification is a nice problem for English football to have in comparison to the problems of the 1980’s when football stadiums were becoming charnel houses for the urban proletariat.

Who do we have to thank (or blame) for the transformation of the English game? Arsene Wenger? As I've made clear, it's arguable whether Wenger was even responsible for the revival in fortunes of the club that he managed, never mind the entirety of English football, so who was responsible? The unpopular answer is the likes of Margaret Thatcher, Rupert Murdoch and Silvio Berlusconi. The transformation of English football has a material basis to it and the essential ingredient which transformed English football, more than any other factor, was its commercialisation following the break-away from the Football League of the newly created Premier League that was specifically designed to capitalise on revenue from satellite-TV in 1992. The commercialisation of English football is inseparable from the shake-up of the British mass-media, which formed part of the Thatcherite economic revolution that took place in the 1980’s. Rupert Murdoch’s media empire was one of the biggest beneficiaries of this economic revolution and in the early-1990’s, in the wave of Italia 90-inspired Gazza-mania, Murdoch alighted upon football as a means of bringing subscription-based satellite-TV to the masses. The rest, as they say, is history. Additionally, changes to European football at the continental level, which we have Silvio Berlusconi to thank or blame, namely the expansion of the European Cup in 1992 into what is now the Champions League, have transformed the economic landscape for all European clubs and accelerated the changes taking place in the English domestic game following the rebrand of the English top-flight in 1992.

The commercialisation of football, which in England we have Margaret Thatcher and Rupert Murdoch to thank or blame, has utterly transformed it, for both good and ill. On the positive side of the ledger, new levels of professionalism have emerged - which the stories about Wenger banning alcohol and making his players eat steamed fish and veg are alluding to - and the result is players like Christiano Ronaldo who have taken sporting asceticism in the pursuit of footballing excellence to heights unimaginable only a few decades ago. To put things in perspective, when the best player in the world in the 1980’s, namely Diego Maradona, was 32, he was overweight, Cocaine-addled and past his peak at middling Sevilla but when the two best players of the 2010’s were 32, on the other hand, Christiano Ronaldo was winning his 4th Champions League and his 5th Ballon d’Or at Real Madrid, whilst Lionel Mess was winning his 10th La Liga and 6th Ballon d’Or at Barcelona. The days when the world’s greatest players could get away with being slightly overweight (Puskas,) a smoker (Cruyff,) an excessive drinker (Best) or a Cocaine-addict (Maradona,) are long-gone and in their place are footballing ascetics like Christiano Ronaldo and family men like Lionel Messi who lead lives low on scandal but high on trophies and goal-scoring records. Seeing the world’s greatest players reach new heights of consistency and longevity is undoubtedly a positive and has resulted from changes in the wider economic landscape of football. Now that football is truly big business, star players are literally precious commodities who play on pitches closer to manicured lawns than the bogs of yesteryear and are afforded greater protection on the pitch than the likes of Diego Maradona could have ever dreamed of too, in order to minimise their risk of injury. Greater remuneration off the pitch has also helped to drive new levels of ultra-professionalism also and the super-human statistics generated by the likes of Ronaldo and Messi are surely testament to its efficacy.

THE GLOBALISATION OF ENGLISH FOOTBALL

The other corollary of English football’s commercialisation has been its globalisation. In 1992, when the English top-flight rebranded itself as the Premier League, less than 5% of squads were made up of foreign players, but by 2004 nearly 60% of Premiership squads were foreign and they hailed from sixty-one different countries. The current figure is closer to 70%, which is higher than other comparable leagues. Premier League clubs spent £2.8bn on players during the 2022-23 season, but just 3% of which (£25m) was spent on acquiring players from the lower leagues within England, whilst a record 85% was spent on players from outside of the UK. It's now been 24 years and counting since an English Premier League side fielded an all-English starting-11. There are currently only 6 English managers out of the 20 sides in the EPL, whereas Gipuzkoa, Spain’s smallest province, which is only half the size of Cornwall, up until recently provided a quarter of Premier League managers alone. It's been 21 years and counting since an English manager led a club to English title-success and it's been 37 years and counting since either Manchester United and Arsenal had an English manager too. When it comes to club ownership, a similar story emerges. Up until relatively recently foreign ownership of English football clubs was unheard of but has now become commonplace. Clubs like Manchester United, Liverpool, Arsenal and Chelsea are all owned by Americans, often financed with private equity money, while Newcastle and Manchester City are owned by middle-eastern states flush with petrodollars. More than half of English top-flight clubs are now backed by American money and only five are actually British-owned anymore.

To put things into perspective, when Liverpool won their first European Cup in 1977, the owners were English, the manager was English and only two of the eleven players in the starting line-up were not English (the odd ones out being Welshman Joey Jones and Irishman Steve Heighway.) When Liverpool won its fifth European Cup in 2019 (now rebranded as the Champions League) the owners were American, the manager was German and only two of the players in the starting line up were English. English football has reinvented itself by de-Anglicising itself. This process of reinvention has been aided and abetted by the collective memory-holing of the history of English football prior to 1992. Given the state of English football in the latter half of the 1980’s, this impulse is, to some degree, understandable. However, this deliberate historical amnesia takes on a distasteful aspect when one considers the number of retired footballers from the pre-1992 era who have developed neurodegenerative disorders in the context of a lifetime of heading the ball and who have subsequently died prematurely, often in obscurity and financial impecunity, without the support of the game to which they had contributed so much. It's a bit on the nose, in regards to the ruthlessness of the football-business, that as large numbers of retired footballers lose their memories of playing the game, we decide to collectively forgot about them too as part of the process of rebranding English football as something that emerged ahistorically from the ether of satellite television in 1992. This trend is exemplified in the endlessly repeated statistic that Alan Shearer is the top-goalscorer in English Premier League history. This is, of course, true but all it tells us is that he has scored more goals in the English top-flight than anyone else since 1992 but the English top-flight actually started in 1888, not in 1992. Alan Shearer is only the 5th top scorer in the history of the English top-flight since 1888, whilst it is Jimmy Greaves who comes top. Memory-holing English football prior to 1992 is something that started off as a marketing strategy by Satellite TV executives but has now become part of our cultural folklore that is handed down as intergenerational conventional wisdom.

THE GENTRIFICATION OF ENGLISH FOOTBALL

The irony is that as the English national team re-asserted its Englishness, English domestic football de-Anglicised itself. It did so, in part, by instituting 1992 as a kind of cultural year-zero and memory-holing anything that happened before that point but also via its gentrification as the big TV money rolled in. Another irony is that the huge contribution that Scotland has made to English football is one such casualty of this process of cultural and economic de-Anglicisation. English football should really be described as Anglo-Scottish football, such has been the contribution of Scottish players and Scottish managers to English football and such has been the symbiosis between the two countries' footballing cultures since the game’s codification in the Victorian-era. Anglo-Scottish football was rooted in the experiences of its urban proletariat and its industrial heartlands in Scotland and Northern England, areas from which a disproportionate number of the best players, managers and clubs in British football once emanated.

Alex Ferguson, a man who grew up in a tenement in mid-20th century Glasgow, dominated the first two decades of Premier League football. His Manchester United side finished top of the table in 13 of the first 21 seasons of the English Premier League. By rights then, if any manager should be synonymous with English domestic football in the modern-era, it should be him, but instead it is Arsene Wenger who is most closely associated with the dawning of the Premier League era and all the changes that it has subsequently wrought. The unvarnished truth is that because English football underwent widespread gentrification, Alex Ferguson was just too working-class in his origins and too much a product of the industrial-era of Anglo-Scottish football to be the face of change which the newly re-branded English top-flight wished to project to the rest of the world. This is despite the fact that Ferguson won as many English titles in a 21 year period as Arsenal have in their entire history and even though, whilst never a teetotaller, he had also changed players diets and challenged players drinkers cultures, just as Wenger is said to have done at Arsenal.

The myth of Wengerball is the popular narrative that Arsene Wenger was singularly transformative of the English game. This narrative should be seen for what it is, essentially a marketing ploy to rebrand English top-flight football and, in the process, render it more appealing to the middle-class customer base which the footballing authorities sought to attract to the game. Wenger fit the bill perfectly given that he was middle-class, well-educated (with a master’s degree in economics,) and from continental Europe, rather than being a product of working-class, Northern, industrial Britain, as all the great managers of the past had been in English football. The business of English football in the 1990’s did not exist in a vacuum and was subject to the same pressures that the rest of the English economy was under. Wenger as the figurehead for post-1992 English football symbolises an acclimation to the changed economic landscape that resulted from the process of deindustrialisation that was effectuated in Northern England and Scotland and the subsequent shifting balance of economic gravity towards the service economy of South-East England. The function of Arsene Wenger in this scenario is analogous to the role that Tony Blair played in the rebranding of the Labour party. New Labour was a post-industrial rebrand of an industrial-era political party that was rooted in the former coalfields, factories and mills of Northern England, Wales and Scotland. New Labour and the English Premier League both represent adaptations of industrial-era, working-class institutions to the realities of the post-industrial era. This is why Tony Blair and Arsene Wenger had to be the face of those changes whereas Alex Ferguson and Gordon Brown could never be. Ferguson and Brown were too much a product of the older era of industrial Britain to ever convincingly sell the English Premier League and the British Labour party as representing newly redesigned forces of modernisation.

As stated previously, the myth of Wengerball may have started off as a sort of marketing ploy to sell Satellite TV subscriptions but it has now become part of our shared cultural folklore that is handed down as intergenerational conventional wisdom. It has become shared folklore, in part, because it panders to the prejudices and biases of the opinion-forming class who write about football and who shape how we view our footballing history. The socio-demographics of the professions in general are skewed towards the most wealthy in this country and journalism is no different. The wider embourgeoisement of English football is reflected in its football writing, a trend accelerated by the huge success of Nick Hornby’s book ‘Fever Pitch’ in 1992, and in Arsene Wenger they see a proxy for themselves; middle-class, well-educated and cosmopolitan. It's therefore no surprise that the myth of Wengerball is like catnip to the opinion-forming classes who write about football because it allows them to flatter themselves by casting the change-agent of our footballing-history in their own image. Additionally, this view of footballing progress, as engineered by middle-class university-educated technocrats like Wenger, helps to camouflage the fact that the changes in the English game have actually come about because of people like Rupert Murdoch and Margaret Thatcher, right-wing figures who writers of a progressive political bent find unpalatable.

CONCLUSION

The commercialisation of football has changed it beyond all recognition and we have people like Silvio Berlusconi, Margaret Thatcher and Rupert Murdoch to thank or blame for this situation, not Arsene Wenger. The current state of English football, which has gotten into bed with a rapacious gambling industry that milks addicts for profit, not to mention the fact that it has welcomed with open arms a number of dubious figures to own our football clubs who then tried to form a European super league against the wishes of its fans, is primarily the result of the Thatcherite economic model being applied to football. A more clear-eyed assessment of the changes that have taken place in the game over the last thirty years is needed which recognises this fact if we are ever to address the current problems that plague our game, including widespread financial irregularities, and also the reduced level of competitiveness which has resulted from the huge inequalities between clubs that the Champions League in particular has exacerbated. The myth of Wengerball doesn't help us in that cause and acts as a soporific, dulling our perceptions, precisely when we need them to be at their most sharp. Free-market principles will always have their limitations when they are applied to football, we do do not choose our footballing allegiances in the same way that we choose our internet service providers, for instance, and it is high time that those limitations were spelled out more explicitly and robustly.

Nice stuff.

If I remember correctly, Wenger's Myth really took off around the time of the Invincibles. At the same time, with Wenger's revolutionary methods being deployed at Arsenal, a gruff, no-nonsense Proper Football Yorkshireman was doing the same thing at Bolton.

And being laughed at.

On the other hand, Allardyce never had the rumours about being a nonce.

Very nice write-up. In retrospect, 1996 does seem a pivotal year for English football. 1992 obviously the transformative moment structurally but ’96 was the first proper reveal of the long-term effects of the breakaway and TV deals. It should also be noted that 1996/97 was the first season after the Bosman ruling, and when UEFA ditched its ‘max. five foreigners’ rule. Take Man Utd, who suddenly went on a splurge of foreign signings that summer (van der Gouw, Johnsen, Solskjaer, Cruyff, Poborsky), where before they’d largely prioritised homegrown talent. It’s also famously when Middlesbrough brought in a bunch of garlanded foreigners and tried to bolt them onto a team of dogged, but limited, British players. Their relegation can be seen in hindsight perhaps as the moment the PL became an elitist competition, dominated by an entrenched few clubs. No provincial side ever again dared believe they could challenge for the title (one freak season for Leicester excepted).

To give Wenger his due, the Back Four all credit him with prolonging their careers and making them more skillful players. And when the so-called ‘Invincibles’ were about to break Forest’s unbeaten run record, Brian Clough himself said - just a few weeks before he died - that they played the most attractive football he’d ever seen in this country (“they don’t just pass to feet, they pass to each others’ better foot”). I might also contend picking at Wenger for not winning a European trophy. Ironically, the Champions League expansion perhaps made it harder for him and Arsenal to do so than in previous generations - as did playing their home games at Wembley - though admittedly they did blow a couple of great chances in 2000 and 2004.

However, I do agree with the general thrust that Wenger is a little overrated. I would say there are some parallels to the impact Cantona made. Both arrived at a specific moment when they were able to stand out and be a pioneer of sorts. A moment when English football was newly awash with money and unusually open to new ideas, and when local talent was at a relatively low ebb. Our island-nation insularity anointed them as world-class. But when you compare them to their continental contemporaries, they don’t quite match up.

You also make a great point about how and why George Graham too often gets written out of the picture, and a very important one about Margaret Thatcher being a hugely important figure in the creation of the Premier League. I think there is now an acknowledgement in the mainstream football media of her unwitting part in the Premier League’s creation. But I did previously perceive a curious denial that the PL was - is - Thatcherism incarnate. And not just from liberal-leaning fans more likely to credit Fever Pitch for making football 'acceptable' - whatever that really means - but also from conservative commentators and older, Thatcher-voting fans, bemoaning the rapid inflation of players’ wages, even as they celebrated the economic impact she brought to everything else.