THE SUPPLY AND DEMAND OF GUN VIOLENCE IN AMERICA

What causes gun-violence in America? Guns? Shooters? Both? The answer may surprise you! (It’s clearly both)

INTRODUCTION

When it comes to markets, we do not need to have read Adam Smith, or to have studied economics, to intuit a basic understanding of what is meant by the terms ‘supply’ and ‘demand’ or to grasp that there is some kind of relationship between them. But when it comes to social problems however, the logic of supply & demand suddenly becomes much more counter-intuitive.

Take suicide, for instance. The layman understanding of suicide tends to fixate upon demand-side factors related to suicide and to ignore supply-side factors altogether. The layman assumes that when someone enacts lethal self-injury, that this was simply as a result of that person being depressed (a demand-side factor,) often ignoring the role of method and opportunity altogether (i.e supply-side factors,), in the mistaken belief that if one method had been denied to that person, another method would simply have been substituted in its stead. Yet this is not what the evidence from years of research on the subject tells us. Suicide research reveals that the demand for suicide, i.e suicidal ideas themselves, are often momentary and fleeting and therefore: if the opportunity to enact lethal self-injury can be made less immediately accessible, then suicide-rates can be reduced merely by reducing supply (i.e by restricting access to the means of suicide) without substitution into alternative methods.

The near quarter-century long American opioid-related drug-death epidemic, now in its fourth wave, widely seen as representing a trend dubbed ‘deaths of despair' thanks to the popularisation of the concept by economists Angus Deaton and Anne Case, is another notable example of this tendency. The ‘deaths of despair’ narrative lumps drug-related deaths in with deaths related to suicide and also to alcohol (misleading in of itself as they are three different sets of phenomena) and posits that the American opioid epidemic resulted from a situation whereby deindustrialisation created the demand for highly potent opioids in the context of diminished economic prospects for predominantly middle-aged, non-college educated, white Americans, in places like the Rust-Belt and Appalachia and elsewhere.

Whilst Case and Deaton are undoubtedly correct that deindustrialisation has helped to widen a diploma-divide into a veritable diploma-chasm, resulting in diminished life-chances for non-university educated Americans in the process, the ‘deaths of despair’ narrative does not explain why America has an opioid epidemic when so many other nations, who have also deindustrialised, do not (aside from Canada and Scotland.) Nor does this narrative help to explain why the American opioid epidemic took off when it did (in the late-1990’s) given that deindustrialisation in America started much earlier than this (what do we think that Bruce Springsteen was singing about all those years ago?) i.e in the 1970s. As Patrick Radden Keefe put it in his book ‘Empire of Pain,’ which focuses on the role played by the Sackler family & their company ‘Purdue Pharma’ in triggering the initial wave of the American opioid epidemic via their marketing of Oxycodone/Oxycontin:- ‘prior to the introduction of OxyContin, America did not have an opioid crisis. After the introduction of OxyContin, it did.’

In other words, the reason why America has an opioid epidemic, at least in its initial stages, was because of changes in supply, not in demand, and, as a much wider audience is now aware, thanks to TV dramatisations such as ‘Dopesick’ (based on the book of the same name,) it was a case of supply stimulating demand in this case, not the other way round. Before the mass-marketing of highly potent opioids as a mega-dose, long-term treatment for moderate pain, as opposed to a small-dose, short-term treatment reserved for patients dying of terminal illnesses, and before their inevitable diversion into use as a street-drug, there was no huge public demand for the flooding of America with powerful opioids.

THE PROBLEM OF GUN-DEREGULATION APOLOGISM

This same principle applies to America’s gun-death problem too. The ‘deaths of despair’ narrative unwittingly obscures the fact that the American opioid epidemic initially happened because of changes in supply, not in demand, changes that were ultimately linked to the pursuit of corporate profit. Apologists for gun-deregulation in America use exactly the same sleight of hand, whether unwittingly or disingenuously, when obscuring the banal, material & proximal cause of America’s gun-death problem i.e the guns themselves.

As Sarah Churchwell recently wrote in The Atlantic:- ‘ It takes ingenuity to avoid blaming guns for gun deaths. Blame mental illness. Blame doorways. Blame teachers who won't take a loaded weapon into the classroom. A Michigan school district just banned backpacks because a loaded gun was found in a third grader's bag- the third weapon to be found in a backpack in the district this year. There were 44.358 gun deaths in the U.S. in 2022. They weren't all mass shootings, but none of them were caused by a backpack.’

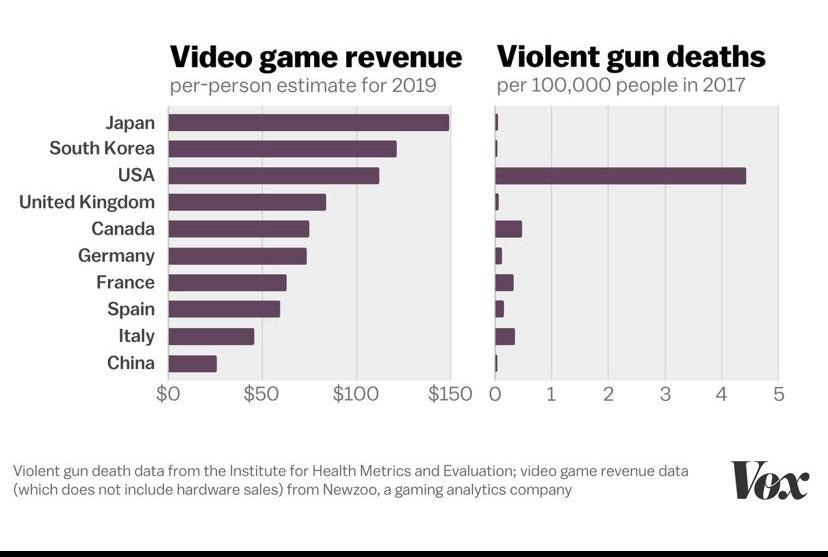

What all apologia for American gun deregulation has in common is this tendency to focus on demand-side factors in relation to gun-violence (i.e to focus on specific characteristics said to be hallmarks of the perpetrators of gun-violence) and to ignore the supply-side factors altogether (i.e the guns themselves,) or, at least, to downplay their importance. A variety of factors have been cited as contributing to rising demand for gun-violence in America including violent video games, family breakdown, fatherlessness, declining religiosity and social trust, plus mental illness, amongst many others. However, many other countries also have violent video games, high rates of family breakdown, fatherlessness, declining religiosity & social trust, plus mental illness, etc, too, but they do not necessarily have comparable rates of gun-violence to America.

Demand-side factors are not completely unimportant, far from it, but, and this is my point, they do not tell us why America in particular has such high rates of gun violence - to put things into perspective: children and teens in America are fifteen times more likely to die from gunfire than their peers in thirty-one other high-income countries combined and America is home to five percent of the industrialised world’s population under 15 years old, but yet accounts for 87 percent of the unintentional firearm fatalities involving that age group - when other countries who share many similar features to America, do not.

AMERICAN GUN-VIOLENCE IS A PROBLEM OF SUPPLY NOT JUST DEMAND

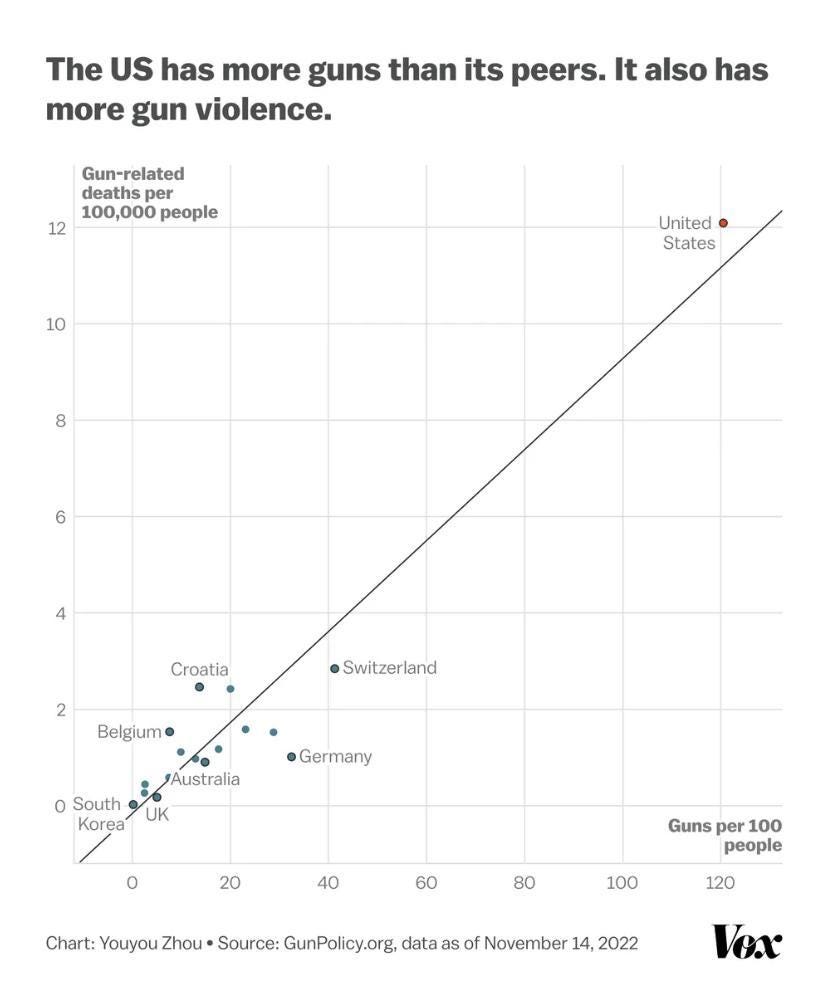

What differentiates America from a country such as Switzerland, for example, who also have a large number of guns amongst its civilian population too, is not just the sheer number of guns in circulation i.e an increased supply of guns, which is much larger than in Switzerland —to put things into perspective: Americans make up less than 5 percent of the world’s population, yet they own roughly 45 percent of all the world’s privately held firearms—but also the increased loosening of restrictions related to their sale and use i.e the increased accessibility of guns (more immediately accessible than in Switzerland.)

Apologists for gun deregulation in America are fond of citing Switzerland as an example of a country with a relatively large number of guns but with a relatively low level of gun-violence. However, even Switzerland accepts that in response to mass-shootings, and other forms of violence involving firearms, the appropriate response, at a societal level, in order to reduce the risk of their recurrence, is to tighten regulations pertaining to their sale and use. Whereas America has moved in the opposition direction, in response to increasing levels of gun-violence, by liberalising restrictions pertaining to their sale and use, despite evidence that this has contributed to an escalating number of resulting harms.

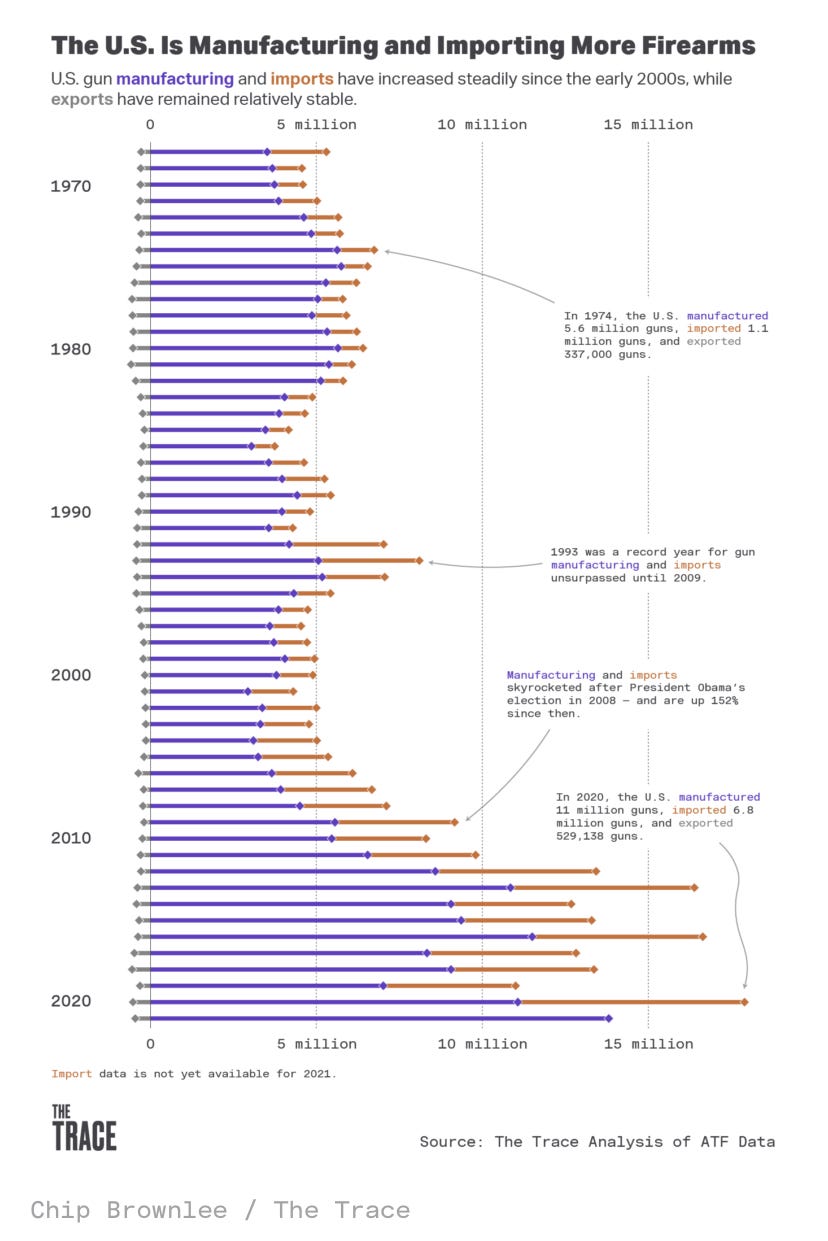

The proliferation of handguns, plus their increased accessibility/availability in a wider variety of settings, (i.e changes in supply,) has implications for gun-violence in America, given that the majority of gun-violence is perpetrated with handguns and given that, as Anthony Braga and Phillip Cook put it, in their book ‘Policing Gun Violence:- ‘guns that are sold to civilians are becoming more lethal over time, with the market increasingly dominated by weapons featuring higher capacity magazines and using larger calibre ammunition…. The transition from revolvers to semi-automatic pistols and from smaller to larger calibre handguns mirrors national trends in handgun production in the United States between the 1980s and 1990s. Another noteworthy trend has been the strong growth in sales of assault weapons—military-style semi-automatic firearms that accept a large, detachable magazine holding 50 rounds or more. These have become the predominant weapon used in mass murders.’

THE PARETO PRINCIPLE AS APPLIED TO AMERICAN GUN-VIOLENCE

The Pareto principle states that, for many outcomes, roughly 80% of consequences come from 20% of causes, and a similar statistical distribution also applies to the American gun-violence problem too (and to all forms of violence in truth.) In other words. American gun-violence is spatially, demographically and geographically concentrated. In America this means that a large proportion of gun-violence emanates from a relatively small number of young black men in urban settings. However, it has to be said that even the white-American homicide-rate is over four times larger than the Swiss homicide-rate and is also much higher than the rate of white Europeans in general.

This is the subtext to much of the right-wing opposition to gun-control, namely the subject of race/ethnicity. Comedian Dave Chapelle once joked that if black Americans started buying guns en masse then this would be the one thing that would guarantee an increase in support for gun control measures amongst a broad range of white Americans. The irony of that joke is that there is indeed some truth behind it. The 1967 Mulford Act, which prohibited public carrying of loaded firearms without a permit, was crafted with a view to disarming the Black Panthers (a black power group) who were conducting armed patrols in Oakland neighbourhoods at the time.

African-Americans trace their American origins to the Deep South, where homicide-rates have always been the highest in the USA, even to this day. The roots of Deep South violence are theorised by Richard Nisbett to originate in an honour culture derived from the culture of herdsman who came from the fringes of Britain and who were the first white-settlers into the region. Thomas Sowell has theorised that African-Americans in the Deep South internalised this honour-culture, which, as Jill Leovy has pointed out, was then reinforced by the lack of a state monopoly on violence. Barry Latzer has theorised that the great migration (which saw African-Americans in the 20th century move to the rest of the USA in large numbers for the first time) then spread this Deep South mode of violence, rooted in honour-culture, to the rest of the USA, subsequently resulting in the great violent-crime spike of the 1960’s, 1970’s and 1980’s.

THE GREAT VIOLENT CRIME SPIKE AND ITS BALEFUL CONSEQUENCES

In 1963 there were only 4.6 homicides for every 100k people in the USA but the national homicide rate then rose in the later half of the 1960s, more than doubling between 1963-1974. The overall US homicide rate increased by 44% between 1960 and 1970 alone. It wasn't until the 1990’s that the American homicide-rate dropped in a significantly sustained fashion. Between 1991-2014, the national murder rate dropped by more than 50%, from 9.8 to 4.4 killings per 100k people. The American homicide-rate has fluctuated since 2014, spiking notably in 2020, but it has never again reached anywhere near the levels of the bad old days of the 1960’s, 1970’s & 1980’s. The bad old days may be over but they have had a lasting impact on American politics which endures.

As Mark Joslyn has written, in his book ‘The Gun Gap,’ it was during the period of the great violent-crime spike of the 1960’s, 1970’s and 1980’s that the modern gun-rights movement was born, led by a newly radicalised NRA. A period when gun-owners and non-gun owners sorted themselves into different political parties. This has subsequently stymied efforts to implement effective gun-regulation because it requires bipartisan consensus to be passed through the American legislature.

Non-Americans assume that the American aversion to gun-control has its roots in the 18th century embedding of a right to bear arms in the American constitution, but as books by Saul Cornell & Robert Spitzer have explained in depth, interpretations of the meaning of the 2nd amendment have changed over time and the 2nd amendment has never been an impediment to the implementation of effective gun-regulation, in any case, until much more recently. As Mark Josyln explains, gun-owners as a group are more cohesive and better resourced than non-gun owners and this is the primary reason why the USA has chosen its recent path of gun deregulation, despite an escalating number of gun-related tragedies.

AMERICAN GUN-VIOLENCE IS A PROBLEM OF DEMAND NOT JUST SUPPLY

This uneven distribution of gun-violence within the population clearly has implications for demand-side interventions to prevent gun-violence i.e interventions which focus on shooters as well as guns, not least of which would be the implementation of effective policing strategies (not just mass incarceration.)

Despite recent claims that Americans are over-policed, the evidence strongly points towards the fact that Americans are, if anything, under-policed. The USA spends less than 1% of its GDP on Policing with poor & nonwhite jurisdictions having far less police protection than richer & whiter jurisdictions.

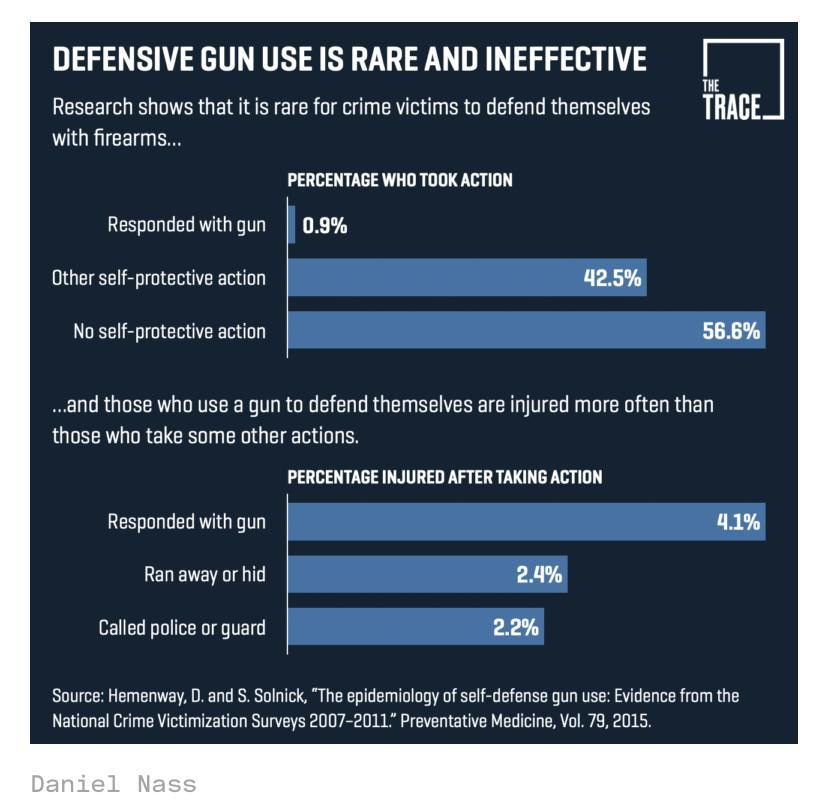

Under-policing also contributes to higher murder rates and increased rates of crime more generally. Under-policing is a big driver of gun-ownership too. Two-thirds of Americans cite self-protection as the primary reason for why they own guns.

As Jennifer Carlson puts it in her book-length sociological portrait of gun-ownership in America:- ‘scholars have found that support for armed civilian self-defence is particularly high in contexts where confidence in police is low. In these contexts, those who act in self-defence are viewed not as rogue vigilantes but as citizens who are responding reasonably to the problem of state impotency. In an atmosphere already primed with stories of police inefficacy, gun carriers over and again saw people’s willingness to rely on the police as naive, if not ignorant.’

Under-policing creates a vacuum filled by mass-civilian gun-ownership for self-protection, even though guns are used for self-defence in America in less than one percent of all crime and having a gun in the home is linked with nearly three times higher odds that someone will be killed at home and even though the USA is not actually more prone to crime than other similarly developed countries.

CONCLUSION

It is clear that for America to reduce its gun-violence problem the implementation of BOTH supply-side AND demand-side solutions are necessary, i.e BOTH effective gun-regulation AND effective policing. Gun-violence may be heavily concentrated, both spatially and demographically, but as Braga and Cook put it:- ‘guns make it easy to kill people. The fact that gun use in violent crime is much more prevalent in America than in other wealthy nations explains much of the observed gap in homicide rates.’ A New Yorker is just as likely to be robbed as a Londoner, for instance, but the New Yorker is 54 times more likely to be killed in the process. Effective gun-violence suppression targets not just shooters but also guns, to posit anything else is to indulge in a false dichotomy, given that in 2020 79% of homicides in America were via firearms.

As Pamela Haag notes, in her book-length study of the supply-side causes of the American gun-violence problem, it is also necessary to target gun-makers too:- ‘The forgotten but ironclad logic that gunned America was the amorality of business, not diabolical intentions of the “Merchant of Death” or the adventures of the gunslinger. The gun culture that exists today in America developed out of an unexceptional, perpetual quest for new and larger markets that had exceptional social consequences. Even so, the thrust of gun politics is toward the mystification of the gun. American gun culture is explained as a legacy of the Second Amendment, militias, Wild West gunslingers, cowboys, the frontier, American individualism, gangs, and the malignant charisma of violence, video games, manhood, and Hollywood. It is explained, in short, as the legacy of almost everything but what it always was—and still is: a business.’

Pamela Haag is undoubtedly correct that rendering the invisible hand of gun-commerce visible for all to see, in regards to the role its plays in America’s gun-violence problem, requires policies to be implemented which, as she puts it:- ‘shift attention from the gun-owner to the gun-maker, and from gun regulation to corporate accountability…restore to guns the same civil liability and consumer regulations and protections that apply to almost every other commodity.’

To some extent what Haag advocates is already happening and is suggestive of one pathway to render the supply-side of America’s gun-violence problem not only visible but also accountable. However, there is little else in the way of evidence that can be discerned which is indicative of America turning away from its current pathway of gun-deregulation and under-policing anytime soon. A pathway that has contributed towards rates of gun-violence which would be unimaginable in any other comparably developed country.

It has been said that the business of America is business and this needs to be kept in mind when analysing the nature of America’s gun-violence problem. Gun-violence, like opioid-overdoses, are as much a problem of supply as of demand and the supply of such products is big business. Until this fact is confronted head-on without obfuscation, there will always be distinct limitations on what can be done to stem the flow of bloodshed. The answer to the question of what causes gun-violence in America, guns or shooters, is clearly both and policy prescriptions need to reflect that fact rather than focusing on just one side or the other.

Good comprehensive take on it.

I am still suspicious the AA community is another serious crutch in this though. Most US (blue) cities that have strict gun enforcement laws find themselves caught between their strict gun laws and policing these communities. A kind of lose-lose situation for them. So they resolve to write strong laws on the books while being incapable of enforcing it on the communities most susceptible for this violence. That isn't true in all of those cities though; NYC I believe has done a good job at this, but comparing that to big hot beds in places like Baltimore, Philadelphia, New Orleans, or Chicago, it really skews the problem in serious ways.

While I think it is still good to point out that even when controlling for that, you are still looking at 4x more than Switzerland. It is a massive challenge to policymakers in the US when their vision of this problem is colored by the "gun-toting redneck" and not the actual major centers of gun violence in the US.

Gun advocates have their own challenges on this for their own failures to confront the problems here. But policymakers will never get these laws working if they have the perspective that the enforcement of it (policing) is regarded as ontologically bigoted to the people they need to police.